Transcriber’s Notes

This is Volume I of a two-volume set. Volume II is available at Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/75617. Index references to pages within that volume are double-underlined here.

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain. It uses the original cover with title and author text added by the Transcriber.

Additional notes will be found near the end of this ebook.

THE

BRITISH BATTLE

FLEET

ITS INCEPTION AND GROWTH

THROUGHOUT THE CENTURIES

TO THE PRESENT DAY

BY

FRED T. JANE

AUTHOR OF “FIGHTING SHIPS,” “ALL THE WORLD’S AIRCRAFT,”

“HERESIES OF SEA POWER,” ETC., ETC.

With Illustrations in Colour

from original water-colour drawings by

W. L. WYLLIE, R.A.

And Numerous Plans and Photographs.

Vol. I.

London

The Library Press, Limited

26 Portugal St., W.C.

1915

TO THOSE

WHO IN ALL AGES BUILT THE SHIPS OF

THE BRITISH NAVY

AND TO THE UNKNOWN MEN

WHO HAVE WORKED THOSE SHIPS

AND SO MADE POSSIBLE THE

FAME OF MANY ADMIRALS.

vii

This book is not intended to be a “history” of the British Navy in the generally accepted sense of the term. For this reason small space is devoted to various strategical and tactical matters of the past which generally bulk largely in more regular “naval histories”—of which a sufficiency already exist.

In such histories primary interest naturally attaches to what the admirals did with the ships provided for them. Here I have sought rather to deal with how the ships came to be provided, and how they were developed from the crude warships of the past to the intricate and complicated machines of to-day; and the strictly “history” part of the book is compressed with that idea principally in view. The “live end” of naval construction is necessarily that which directly or indirectly concerns the ships of our own time. The warships of the past are of special interest in so far as they were steps to the warships of to-day; but, outside that, practical interest seems confined to what led to these “steps” being what they were.

Thus regarded, Trafalgar becomes of somewhat secondary interest as regards the tremendous strategical questions involved, but of profound importance by reason of the side-issue that the Victory’s forward bulkheadviii was so slightly built that she sustained an immense number of casualties which would never have occurred had she been designed for the particular purpose that Nelson used her for at Trafalgar. The tactics of Trafalgar have merely a literary and sentimental interest now, and even the strategies which led to the battle are probably of little utility to the strategists of our own times. But the Victory’s thin forward bulkhead profoundly affected, and to some extent still affects, modern British naval construction. Trafalgar, of course, sanctified for many a year “end-on approach,” and so eventually concentrated special attention on bulkheads. But previous to Trafalgar, the return of the Victory after it for refit, and Seppings’ inspection of her, the subject of end-on protection had been ignored. The cogitations of Seppings helped to make what would have very much influenced history had any similar battle occurred in the years that followed his constructional innovations.

Again, at an earlier period much naval history turned upon the ventilation of bilges. Improvements in this respect (devised by men never heard of to-day) enabled British ships to keep the seas without their crews being totally disabled by diseases which often overmastered their foes. The skill of the admirals, the courage of the crews, both form more exciting reading. Yet there is every indication to prove that this commonplace matter of bilges was the secret of victory more than once!

Coming back to more recent times, the loss of the Vanguard, which cost no lives, involved greater subsequent constructional problems than did the infinitelyix more terrible loss of the Captain a few years before. Who shall say on how many seeming constructional failures of the past, successes of the yet unborn future may not rest?

A number of other things might be cited, but these suffice to indicate the particular perspective of this book, and to show why, if regarded as an orthodox “history” of the British Navy, it is occasionally in seemingly distorted perspective.

To say that in the scheme of this book the ship-builder is put in the limelight instead of the ship-user, would in no way be precisely correct, though as a vague generalisation it may serve well enough. In exact fact each, of course, is and ever has been dependent on the other. Nelson himself was curtailed by the limitations of the tools provided for him. Had he had the same problems one or two hundred years before he would have been still more limited. Had he had them fifty or a hundred years later—who shall say?

With Seppings’ improvements, Trafalgar would have been a well-nigh bloodless victory for the British Fleet. It took Trafalgar, however, to inspire and teach Seppings. Of every great sea-fight something of the same kind may be said. The lead had to be given.

Yet those who best laboured to remove the worst disabilities of “the means” of Blake, contributed in that measure to Nelson’s successes years and years later on. Their efforts may surely be deemed worthy of record, for all that between the unknown designer of the Great Harry in the sixteenth century and the designers of Super-Dreadnoughts of to-day there may have beenx lapses and defects in details. There was never a lapse on account of which the user was unable to defeat any hostile user with whom he came into conflict. The “means” provided served. The creators of warships consistently improved their creations: but they were not improved without care and thought on the part of those who produced them.

To those who provided the means and to the rank and file it fell that many an admiral was able to do what he did. These admirals “made history.” But ever there were “those others” who made that “history making” possible, and who so made it also.

In dealing with the warships of other eras, I have been fortunate in securing the co-operation of Mr. W. L. Wyllie, R.A., who has translated into vivid pictorial obviousness a number of details which old prints of an architectural nature entirely fail to convey. With a view to uniformity, this scheme, though reinforced by diagrams and photographs, has been carried right into our own times.

Some things which I might have written I have on that account left unrecorded. There are some things that cold print and the English language cannot describe. These things must be sought for in Mr. Wyllie’s pictures.

In conclusion, I would leave the dedication page to explain the rest of what I have striven for in this book.

F. T. J.

xi

This book was originally written three years ago. Since it was first published the greatest war ever known has broken out. To meet that circumstance this particular edition has been revised and brought to date in order to present to the reader the exact state of our Navy when the fighting began.

Modern naval warfare differs much from the warfare of the past; at any rate from the warfare of the Nelson era. But if men and matériel have altered, the general principles of naval war have remained unchanged. Indeed, there is some reason to believe that the wheel of fortune has brought us back to some similitude of those early days when to kill the enemy was the sole idea that obtained, when there were no “rules of civilised war,” when it was simply kill and go on killing.

To these principles Germany has reverted. The early history of the British Navy indicates that we were able to render a good account of ourselves under such conditions. For that matter we made our Navy under such training. It is hard to imagine that by adopting old time methods the Germans will take from us the Sea Empire which we thus earned in the past.

F. T. J.

18th June, 1915.

xiii

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | THE BIRTH OF BRITISH NAVAL POWER | 1 |

| II. | THE NORMAN AND PLANTAGENET ERAS | 10 |

| III. | THE TUDOR PERIOD AND BIRTH OF A REGULAR NAVY | 35 |

| IV. | THE PERIOD OF THE DUTCH WARS | 59 |

| V. | THE EARLY FRENCH WARS | 88 |

| VI. | THE GREAT FRENCH WAR | 133 |

| VII. | FROM THE PEACE OF AMIENS TO THE FINAL FALL OF NAPOLEON | 165 |

| VIII. | GENERAL MATTERS IN THE PERIOD OF THE FRENCH WARS | 194 |

| IX. | THE BIRTH OF MODERN WARSHIP IDEAS | 211 |

| X. | THE COMING OF THE IRONCLAD | 229 |

| XI. | THE REED ERA | 264 |

xv

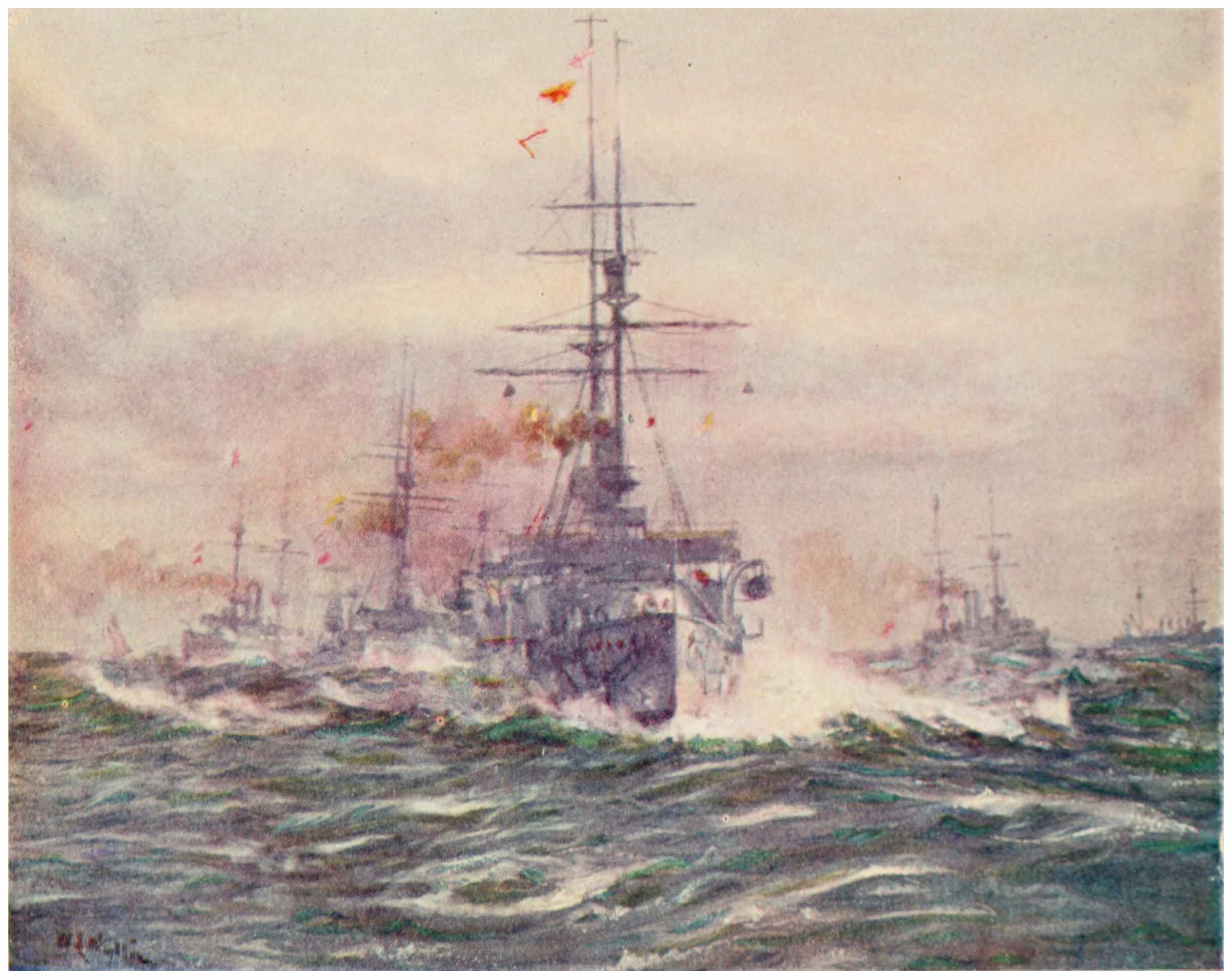

| IN COLOUR FROM PICTURES BY W. L. WYLLIE, R.A. |

|

| PAGE | |

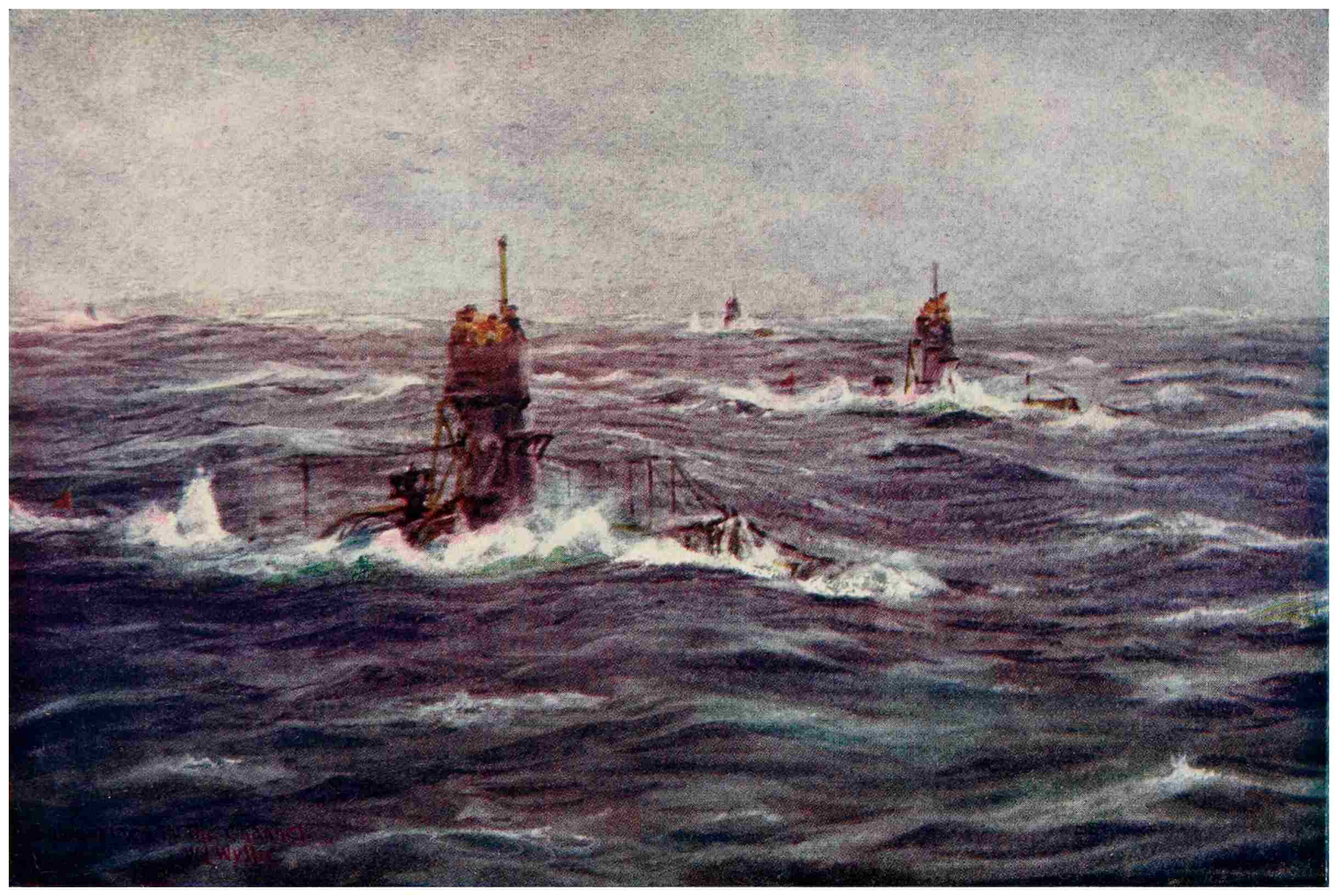

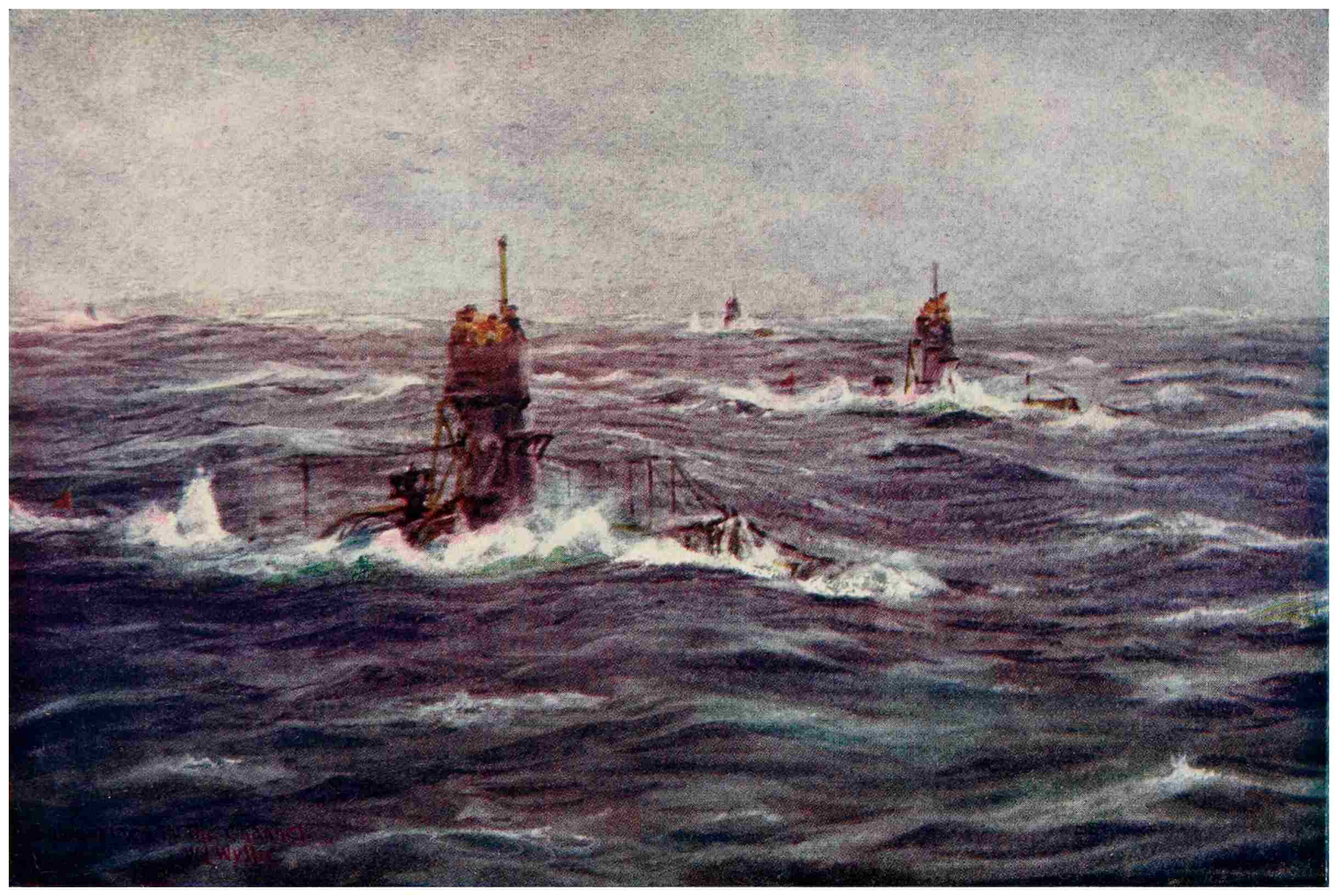

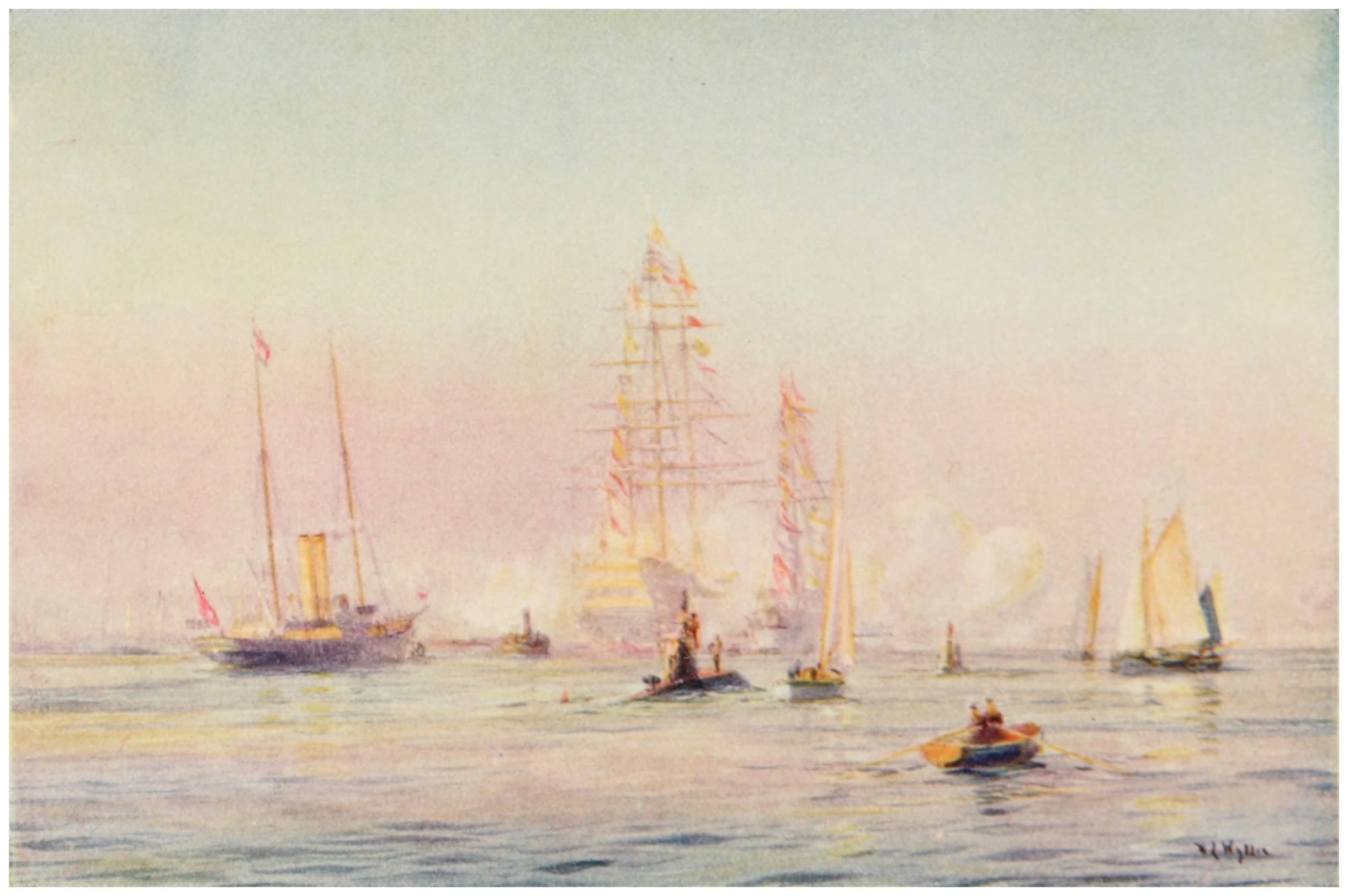

| SUBMARINES IN THE CHANNEL Frontispiece | |

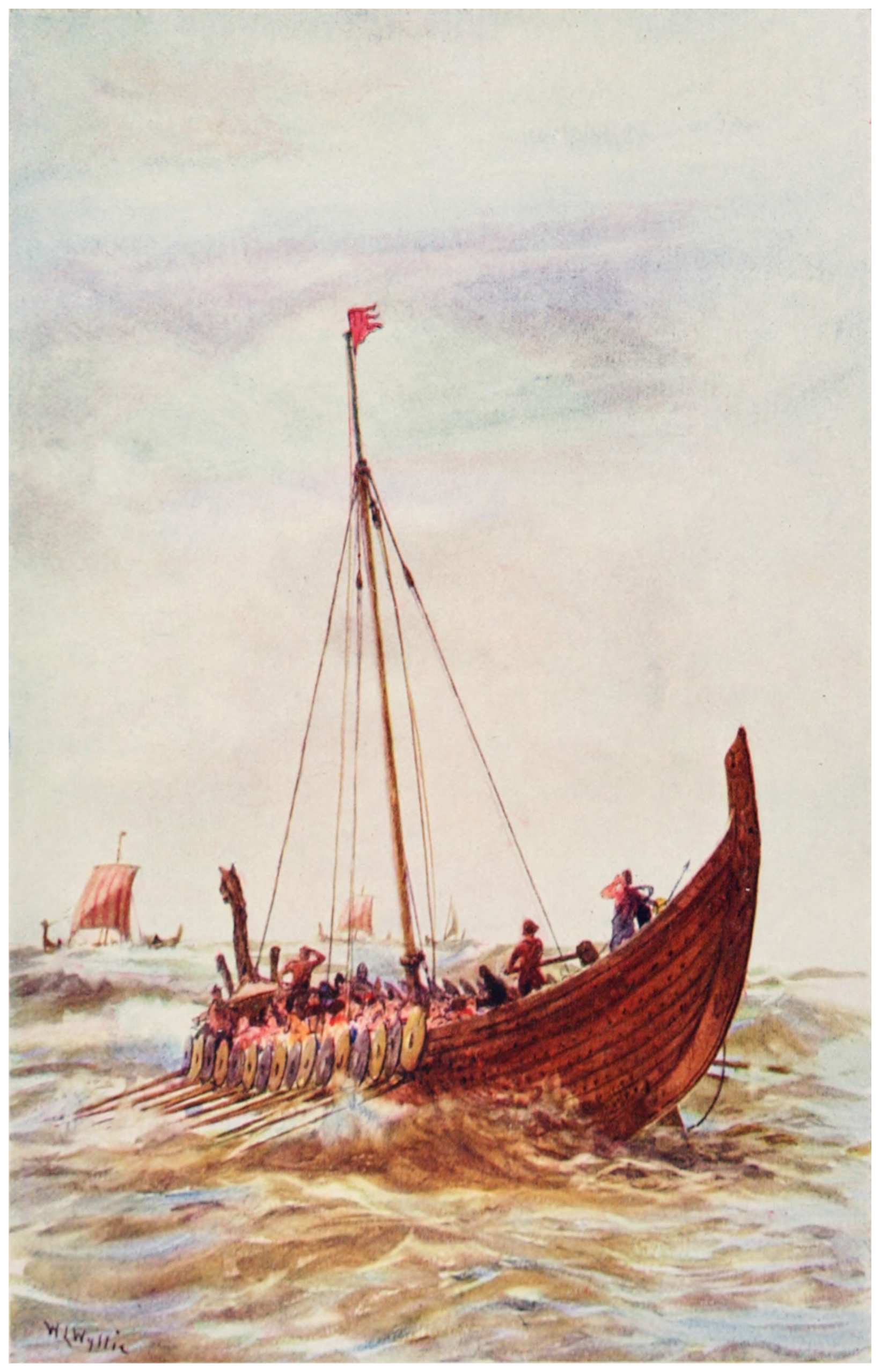

| WARSHIP OF THE TIME OF KING ALFRED | 3 |

| RICHARD I. IN ACTION WITH THE SARACEN SHIP | 13 |

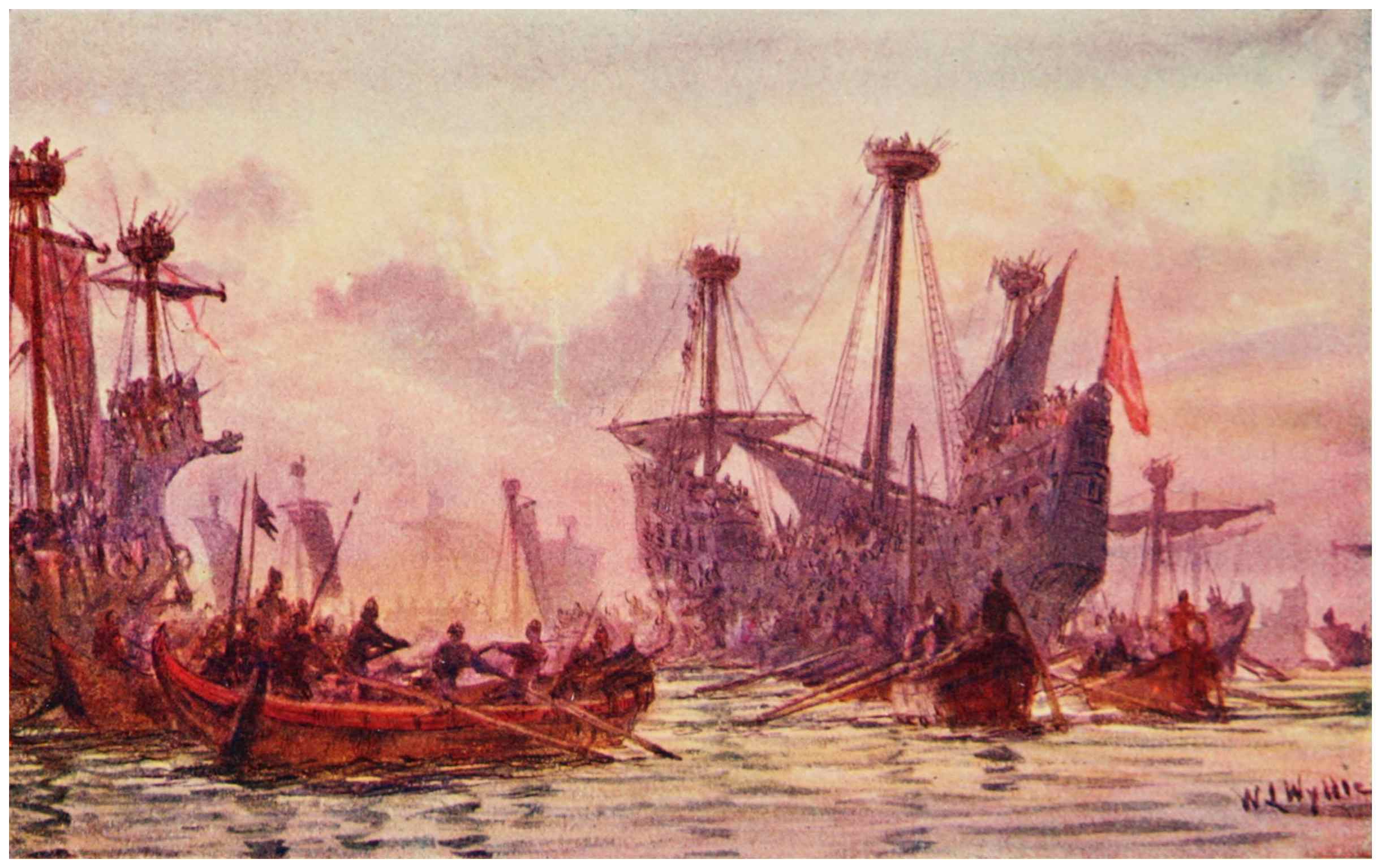

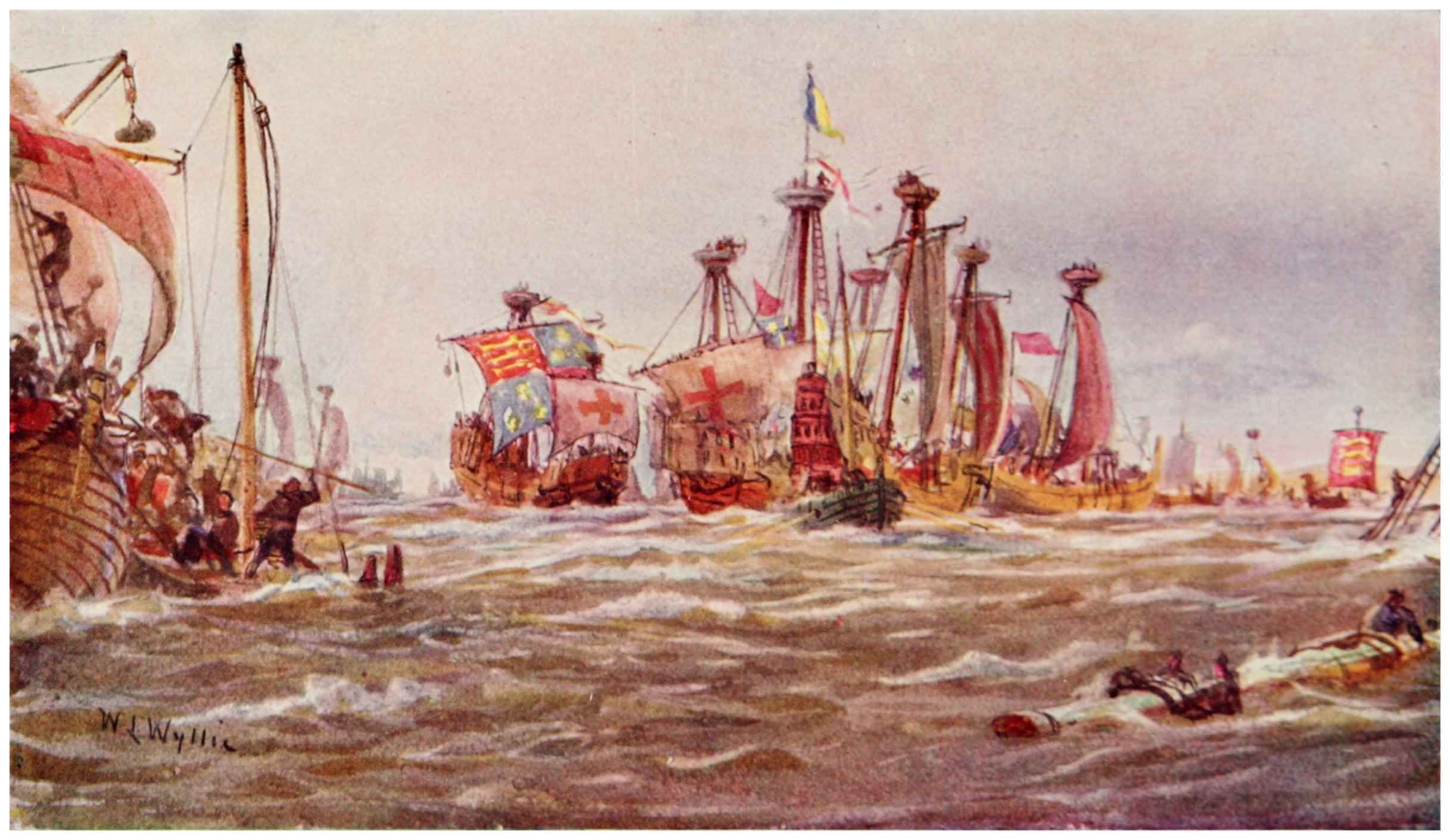

| BATTLE OF SLUYS | 25 |

| PORTSMOUTH HARBOUR, 1912 | 31 |

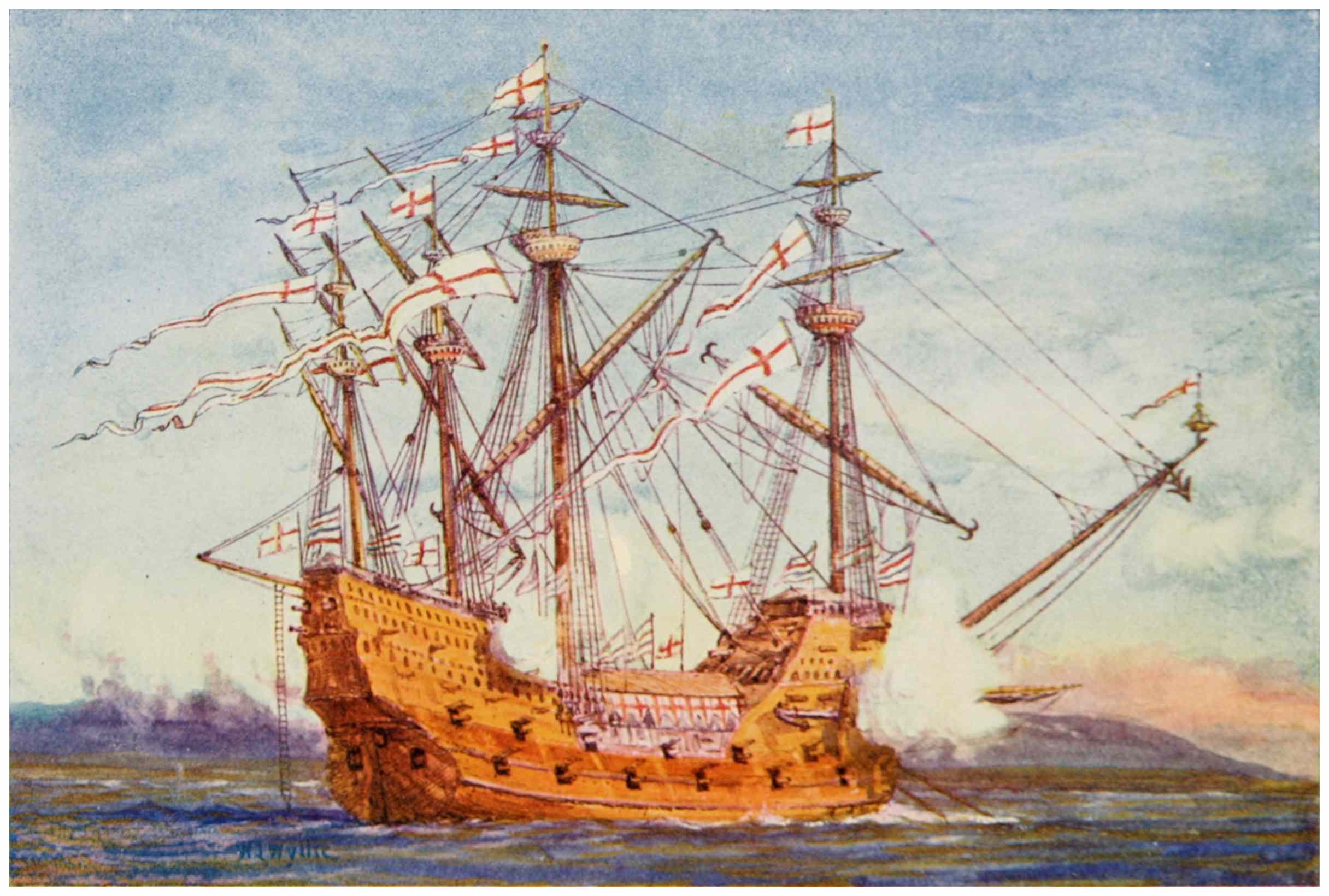

| THE “GRACE DE DIEU,” 1515 | 39 |

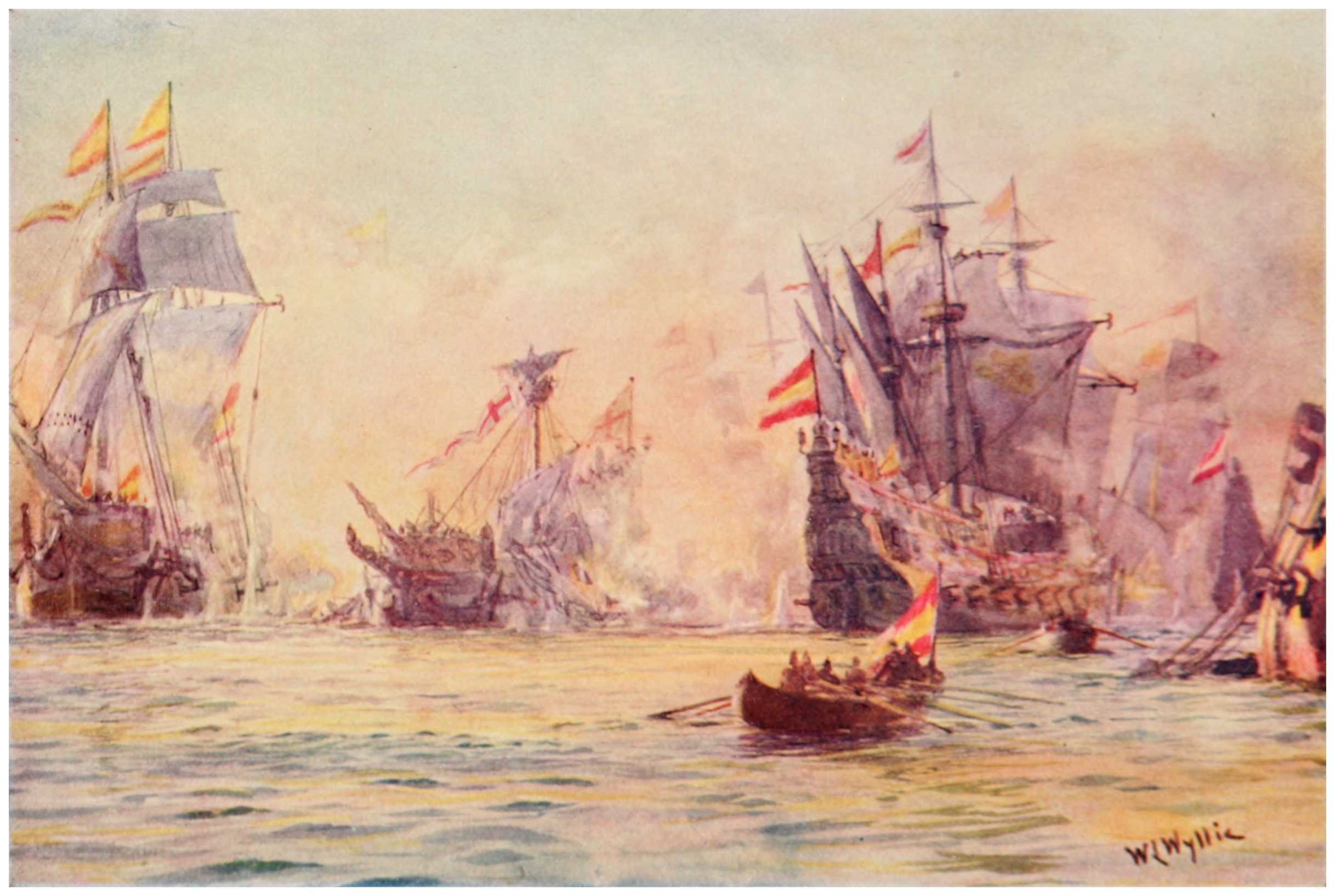

| THE SPANISH ARMADA, 1588 | 51 |

| THE END OF A “GENTLEMAN ADVENTURER” | 55 |

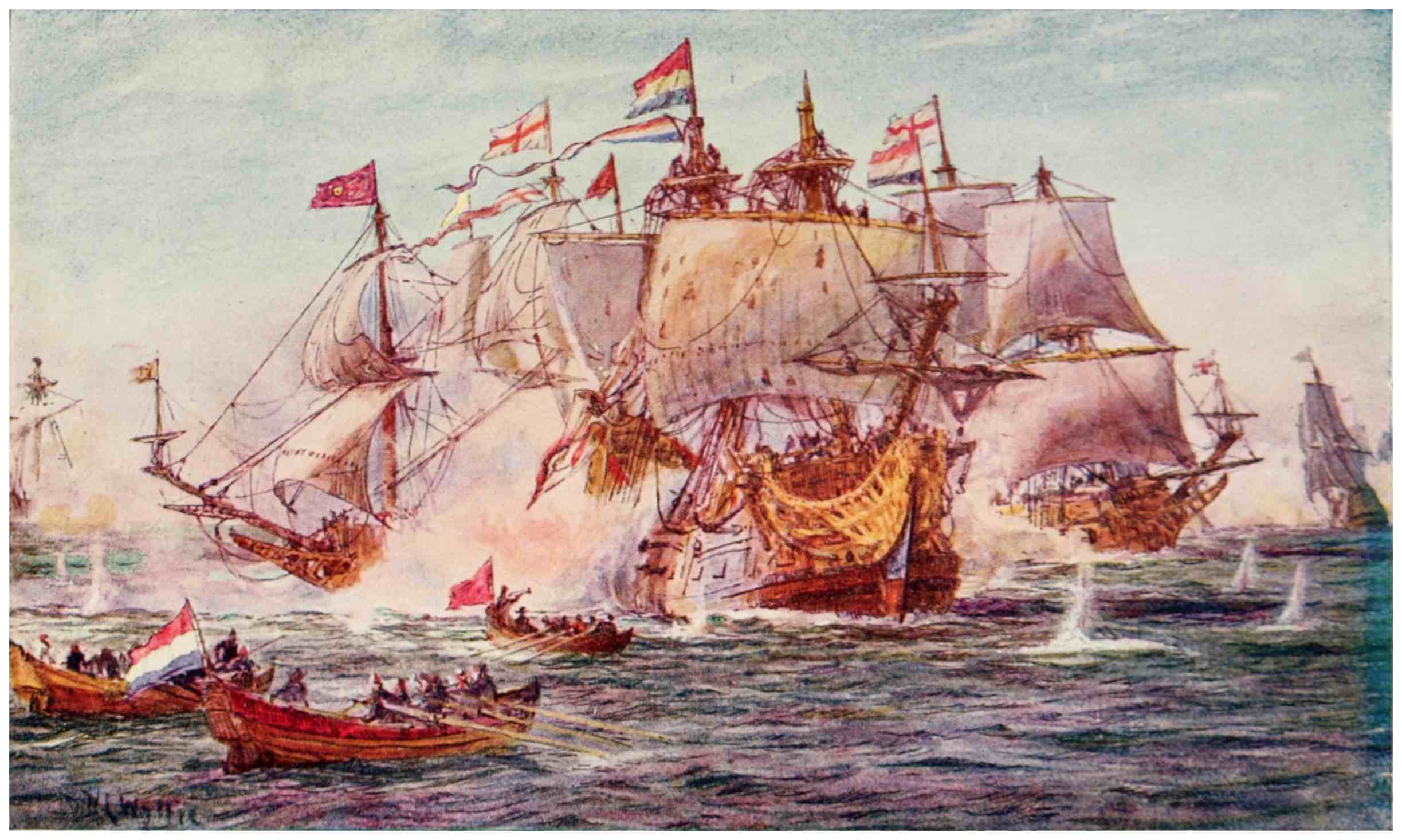

| BLAKE AND TROMP—PERIOD OF THE DUTCH WARS | 77 |

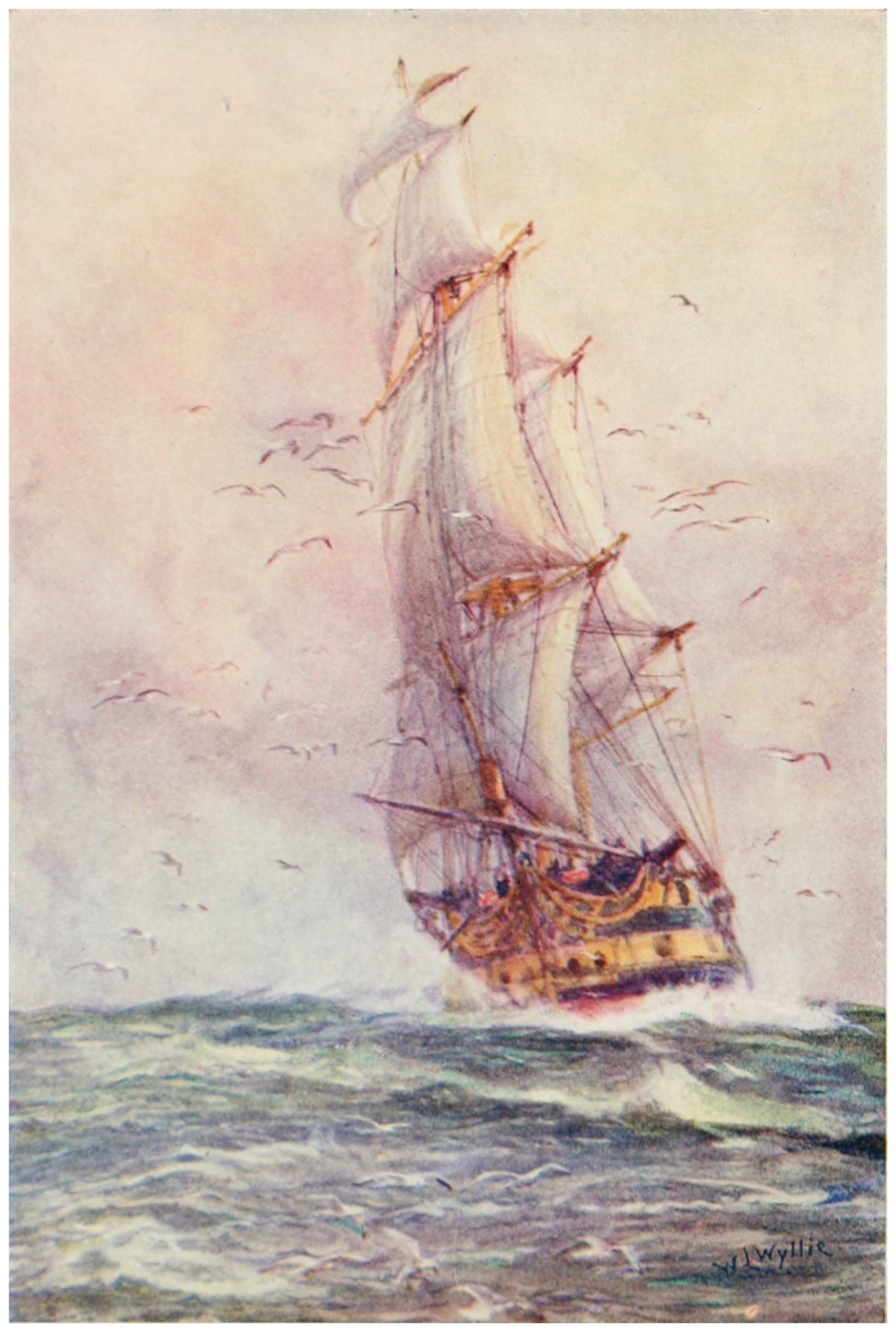

| BATTLESHIPS OF THE WHITE ERA AT SEA | 117 |

| THE “FOUDROYANT,” ONE OF NELSON’S OLD SHIPS | 143 |

| BATTLE OF TRAFALGAR, 1805 | 173 |

| THE END OF AN OLD WARSHIP | 191 |

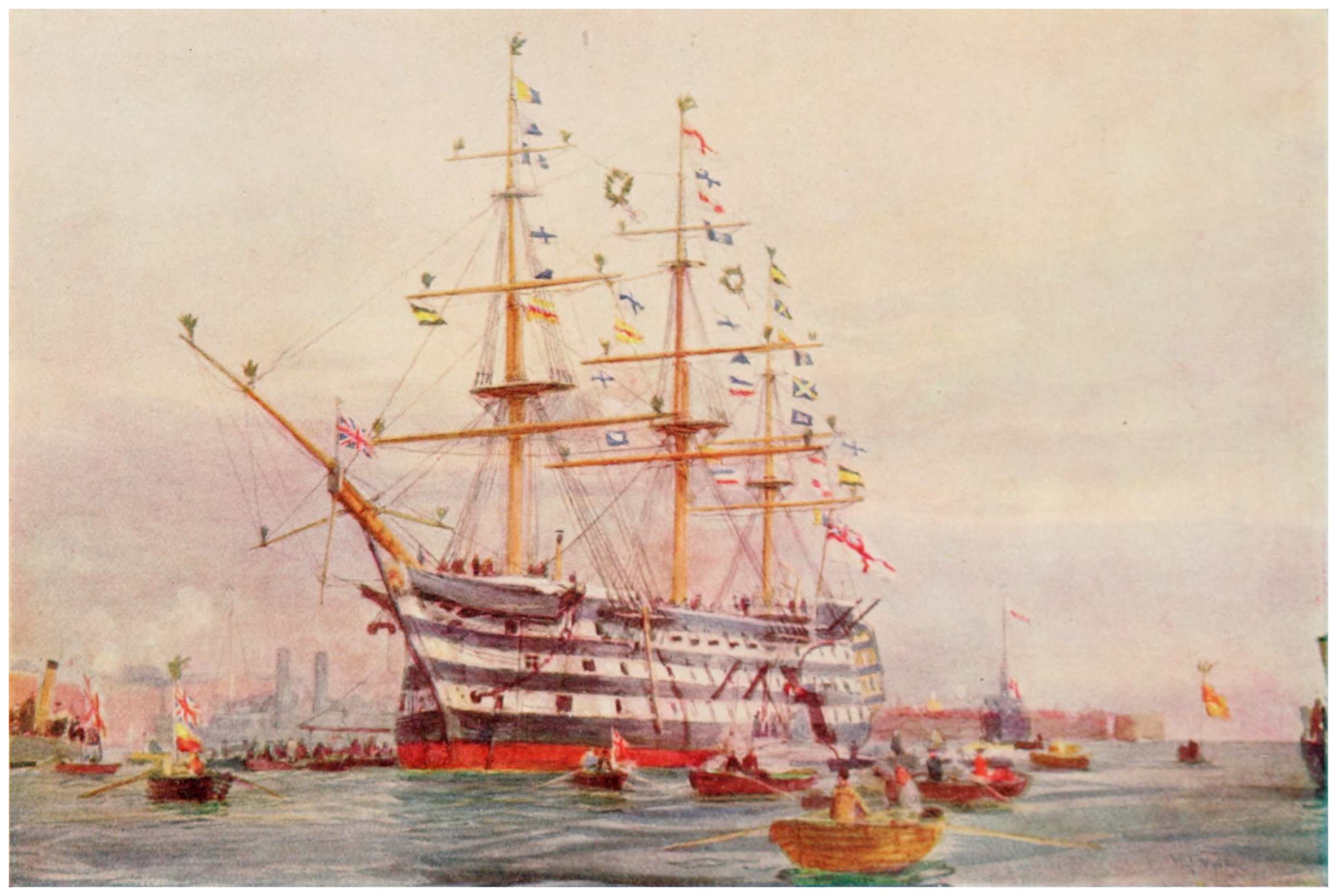

| A TRAFALGAR ANNIVERSARY | 205 |

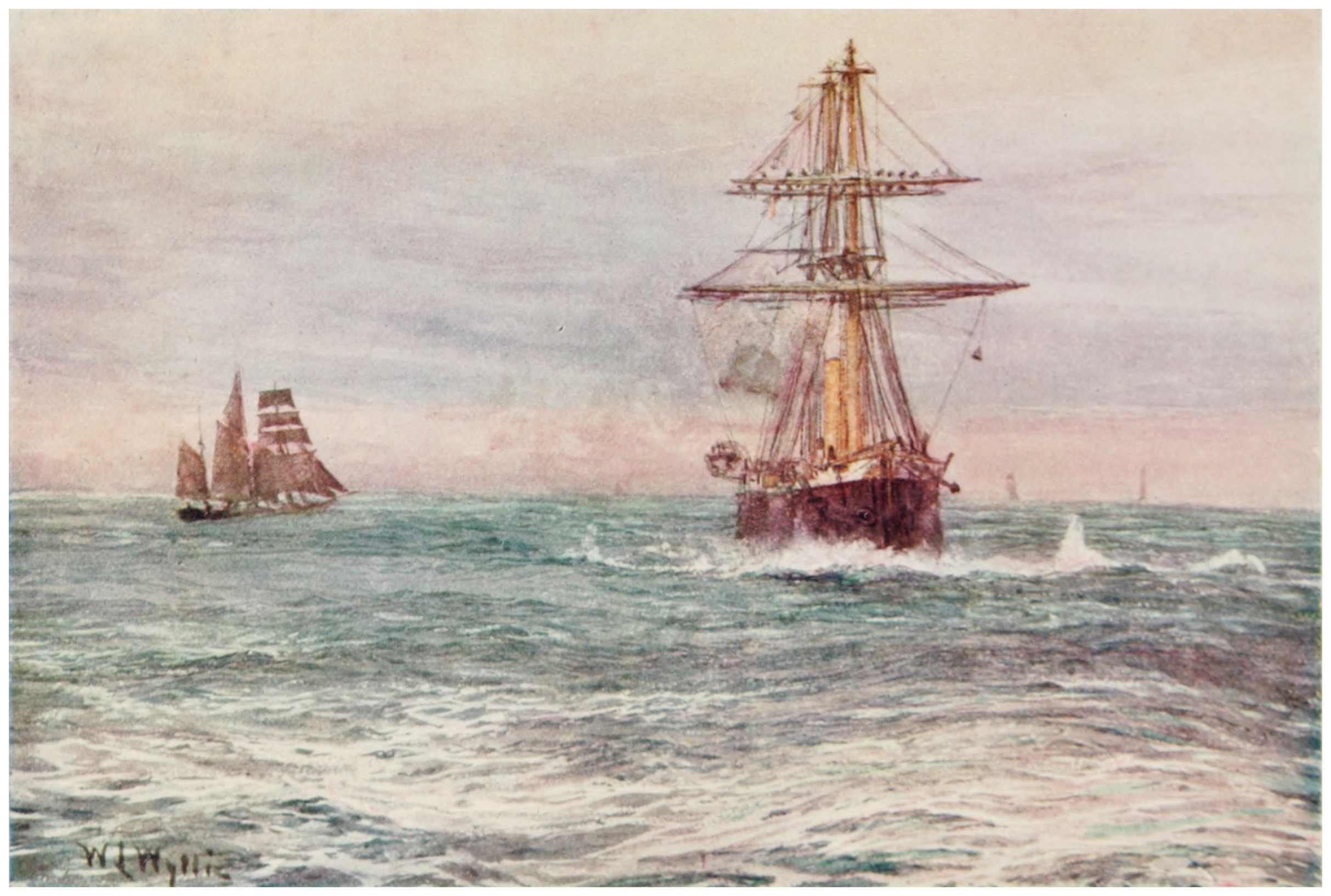

| THE OLD “INVINCIBLE,” 1872 | 293xvi |

| SHIP PHOTOGRAPHS | |

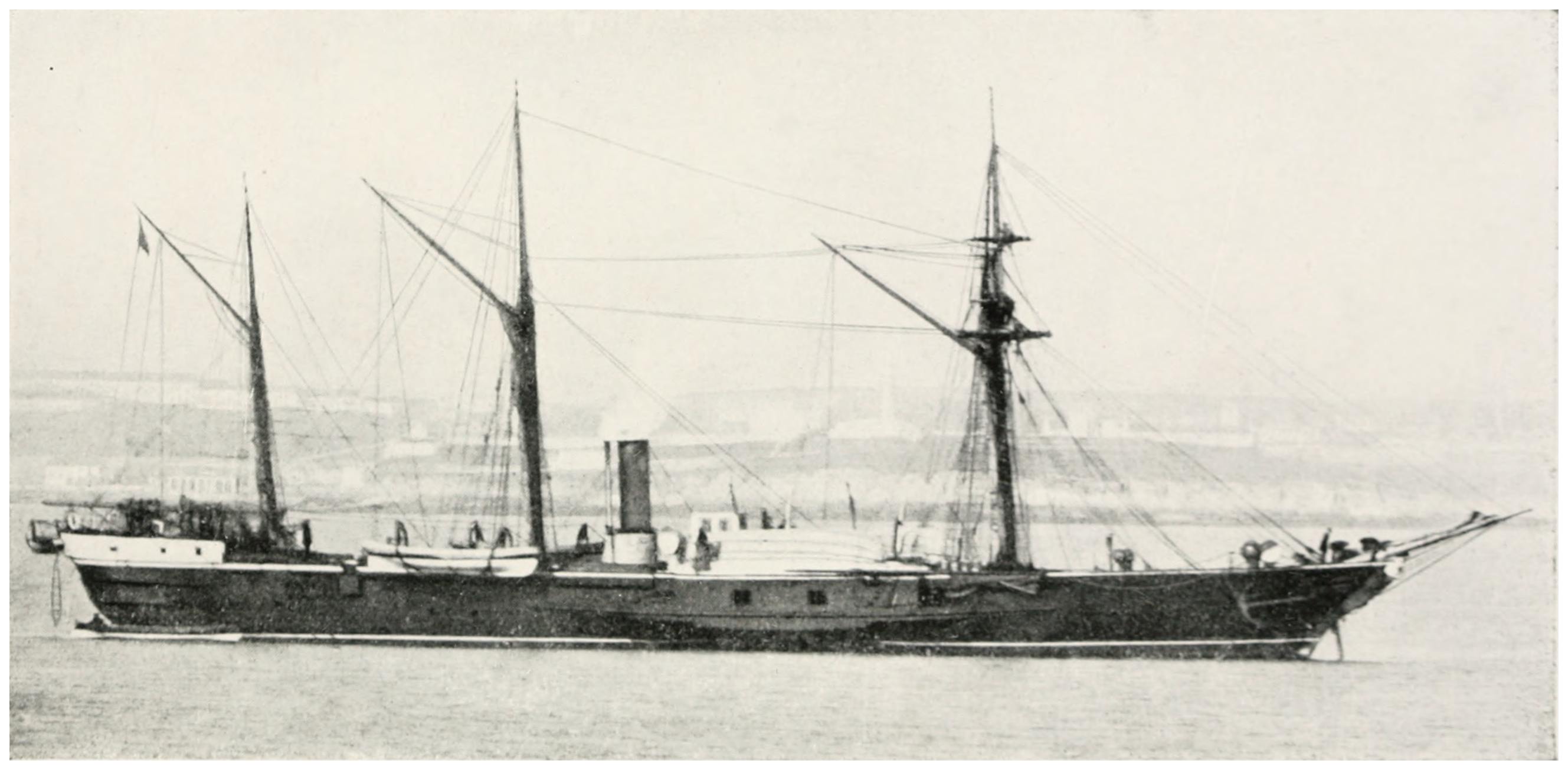

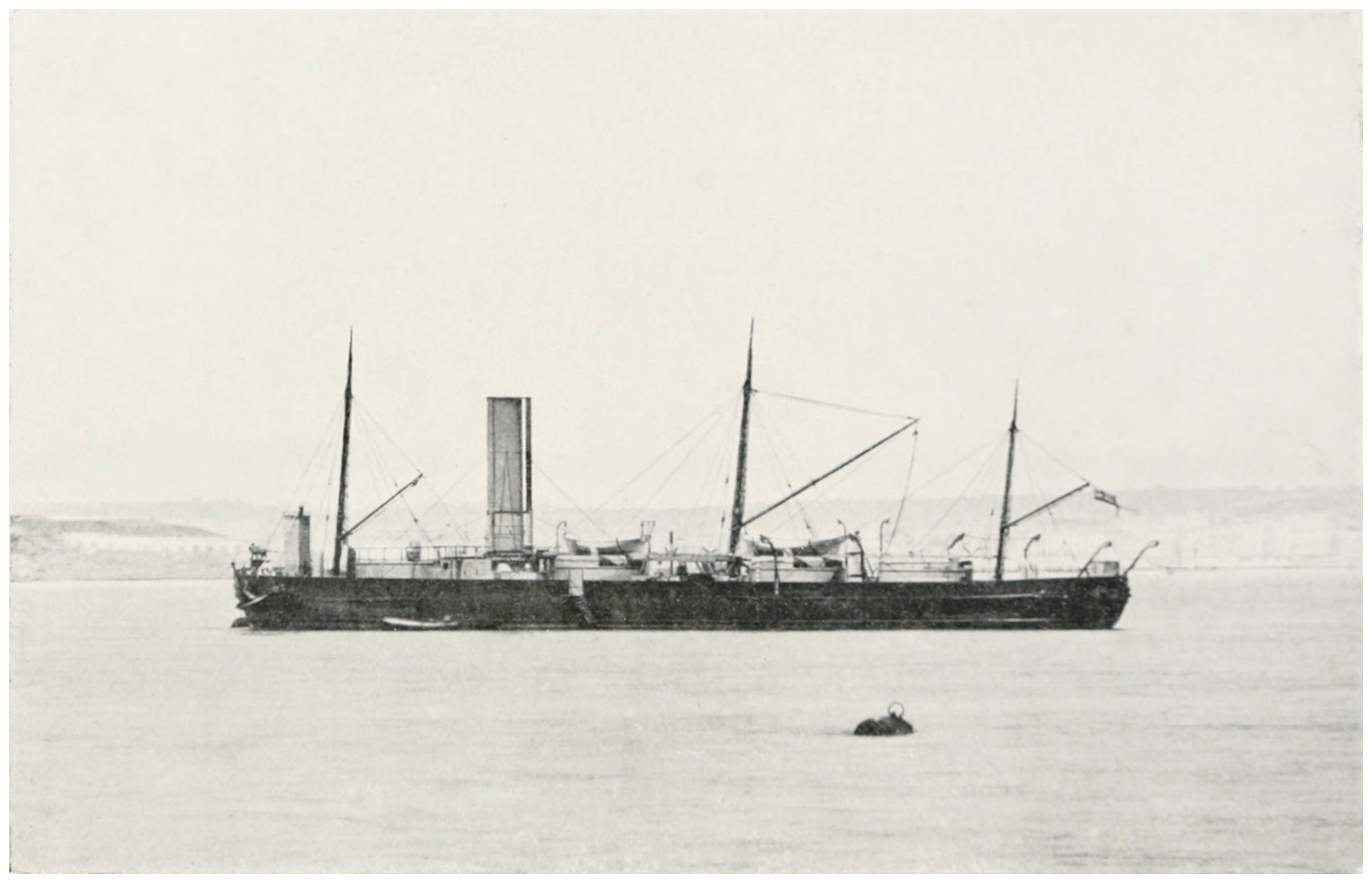

| “SALAMANDER,” PADDLE WARSHIP | 217 |

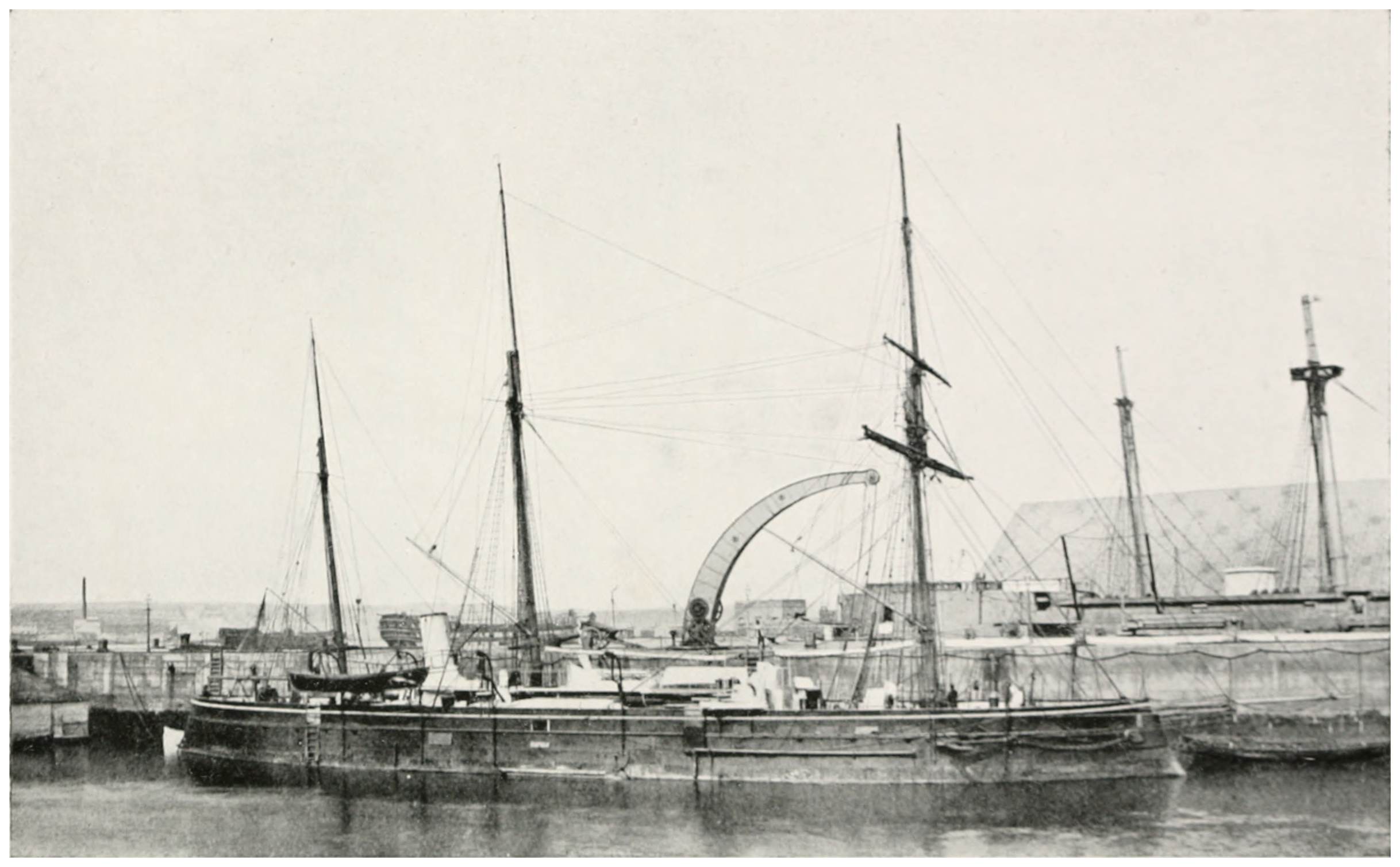

| OLD SCREW WOODEN LINE-OF-BATTLESHIP “LONDON” | 221 |

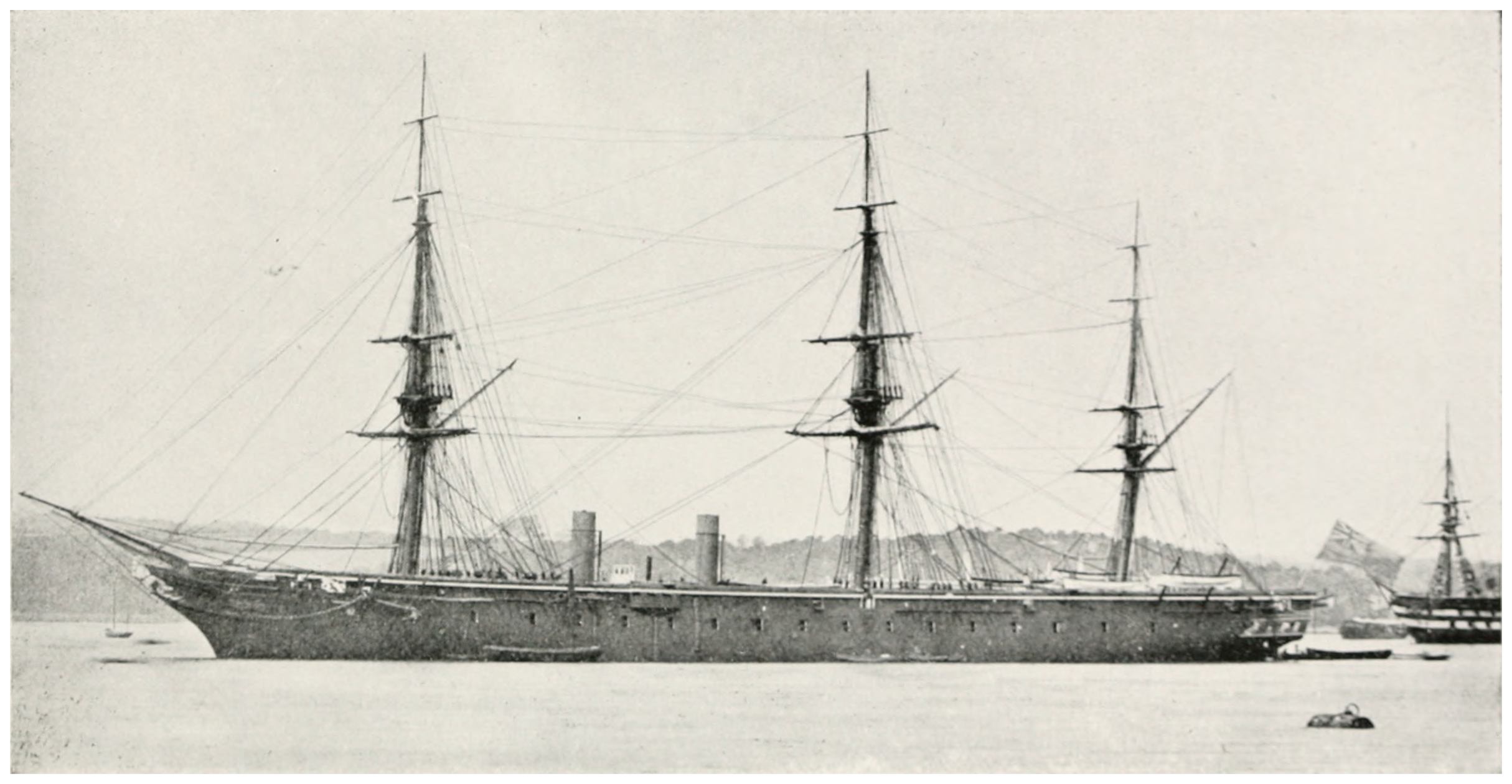

| “WARRIOR” | 251 |

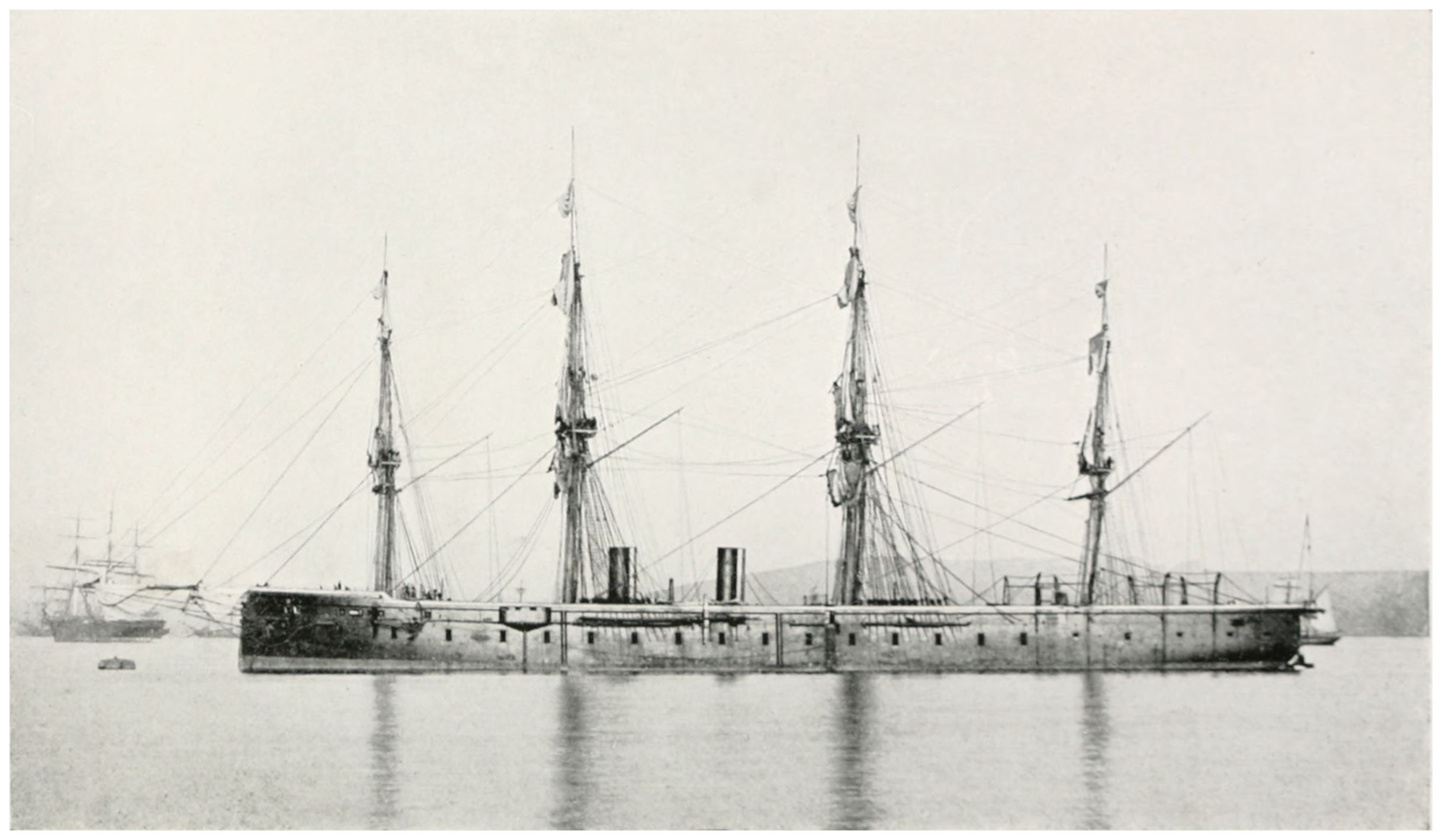

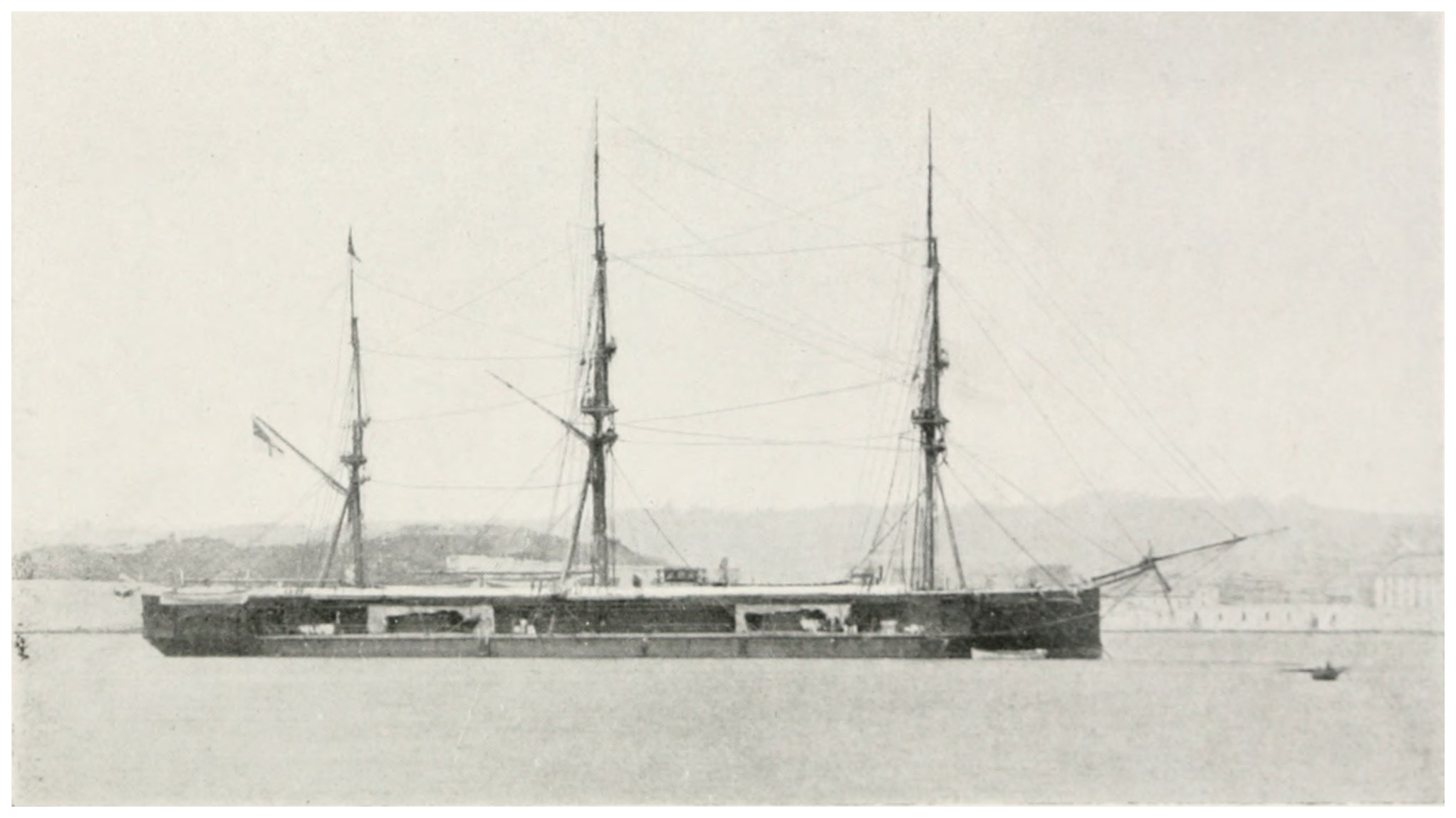

| “ACHILLES” (WITH FOUR MASTS) | 259 |

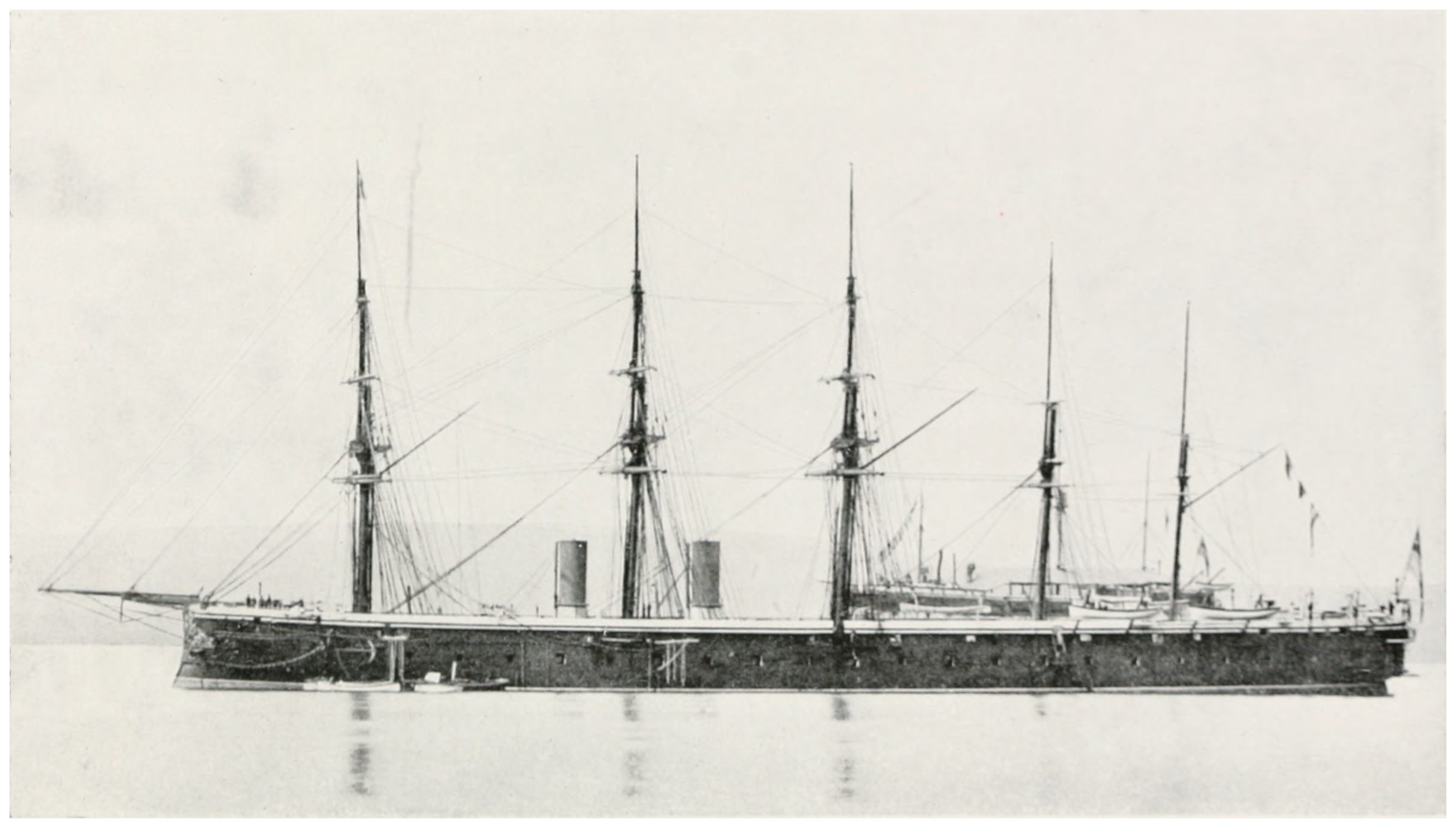

| “MINOTAUR” (AS A FIVE-MASTER) | 261 |

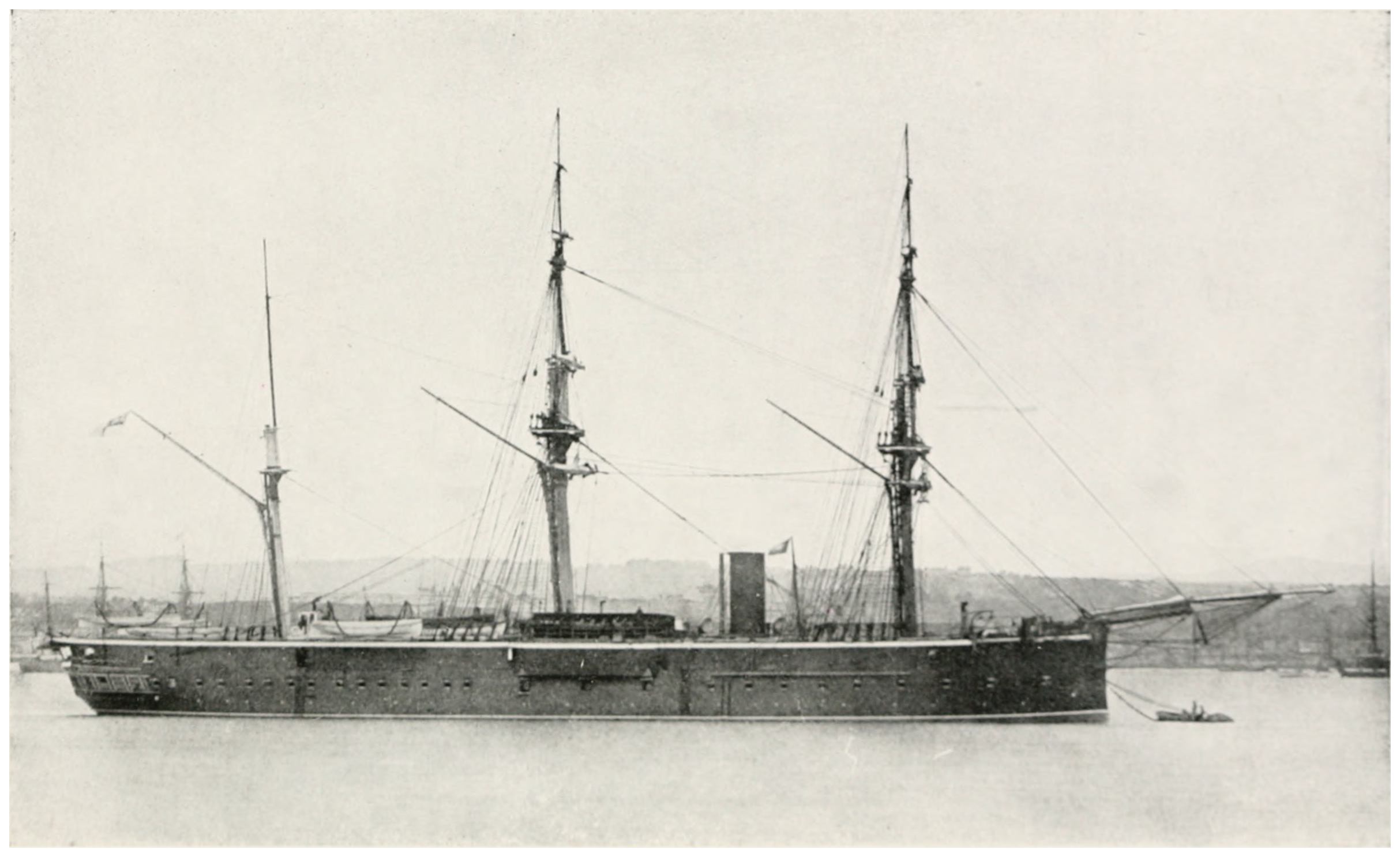

| “BELLEROPHON” | 269 |

| “ROYAL SOVEREIGN” | 273 |

| “WATERWITCH” | 277 |

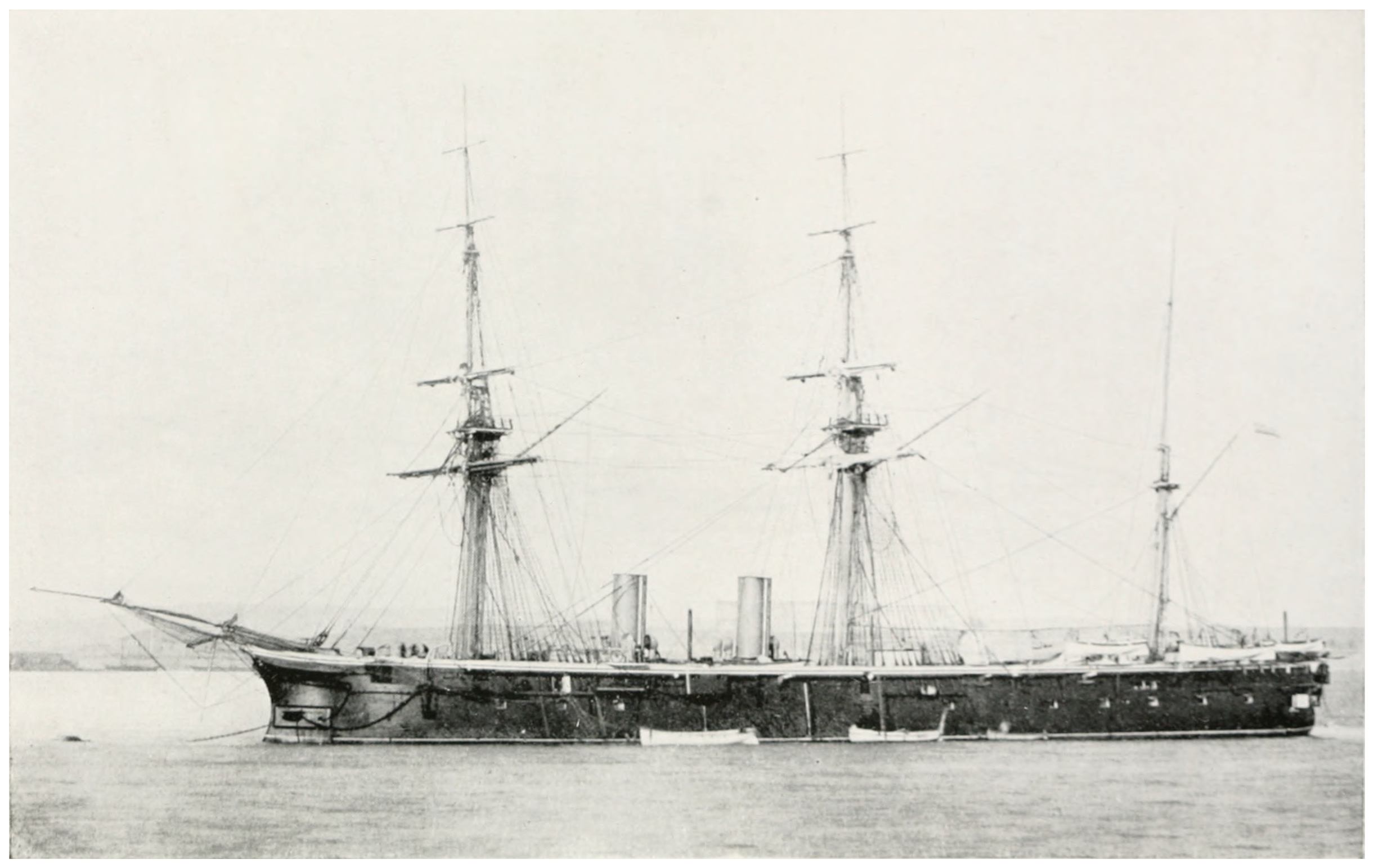

| “CAPTAIN” | 289 |

| “VANGUARD” | 297 |

| “HOTSPUR” AS ORIGINALLY COMPLETED | 309 |

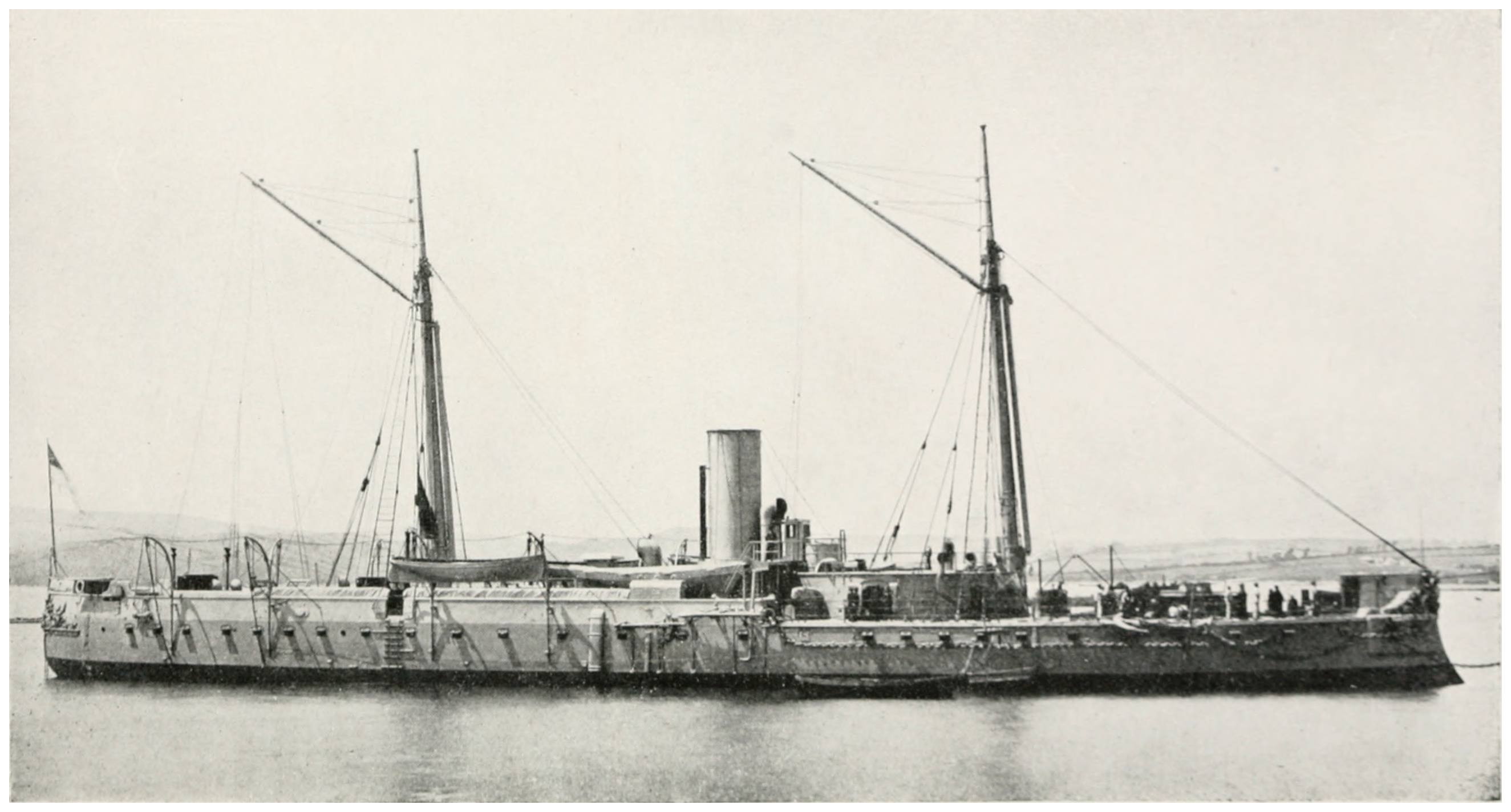

| “DEVASTATION” AS ORIGINALLY COMPLETED | 313 |

| PORTRAITS | |

| PHINEAS PETT | 67 |

| SIR ANTHONY DEANE | 93 |

| GENERAL BENTHAM | 155 |

| JOHN SCOTT RUSSELL | 245 |

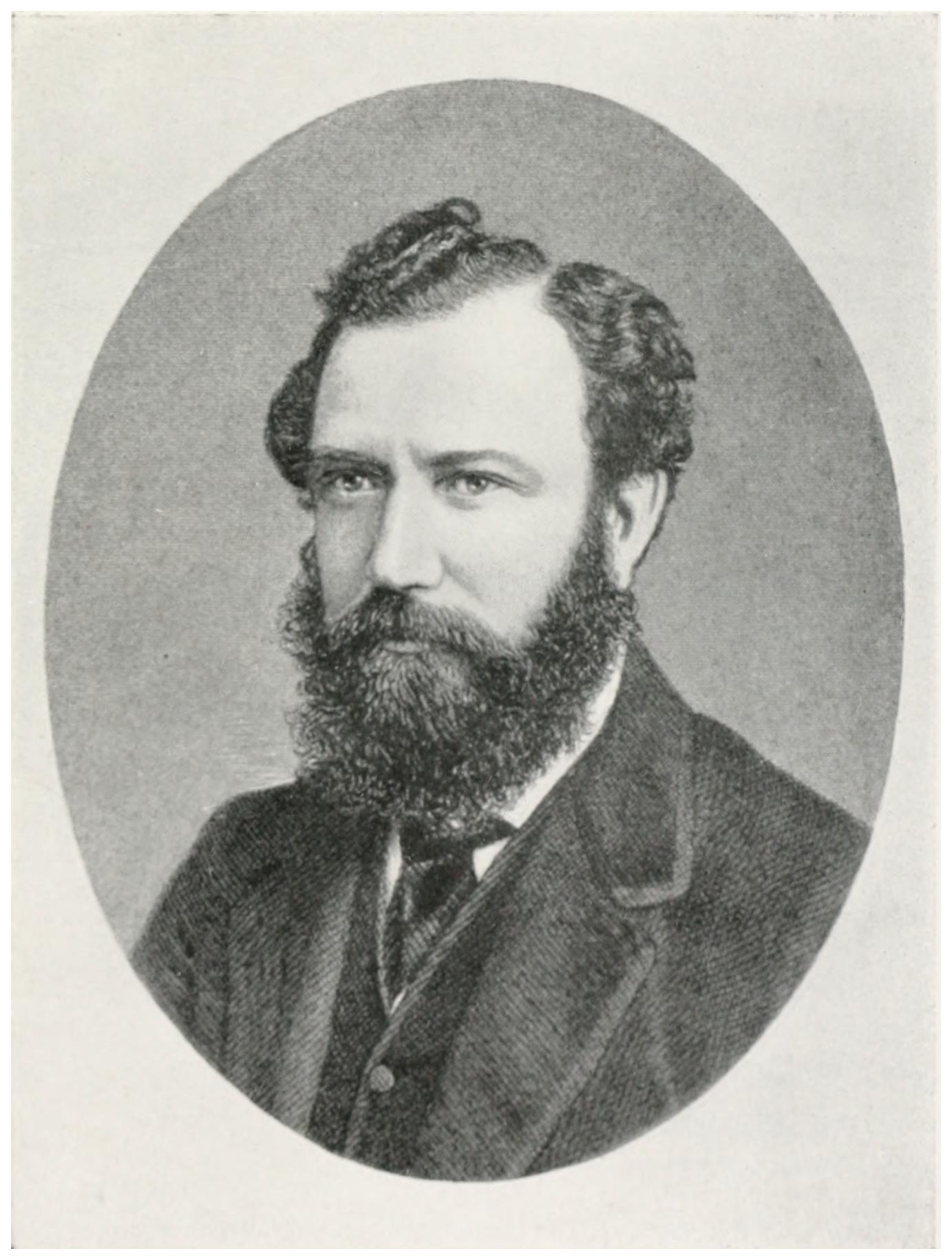

| SIR E. J. REED | 265 |

| PLANS, DIAGRAMS, ETC. | |

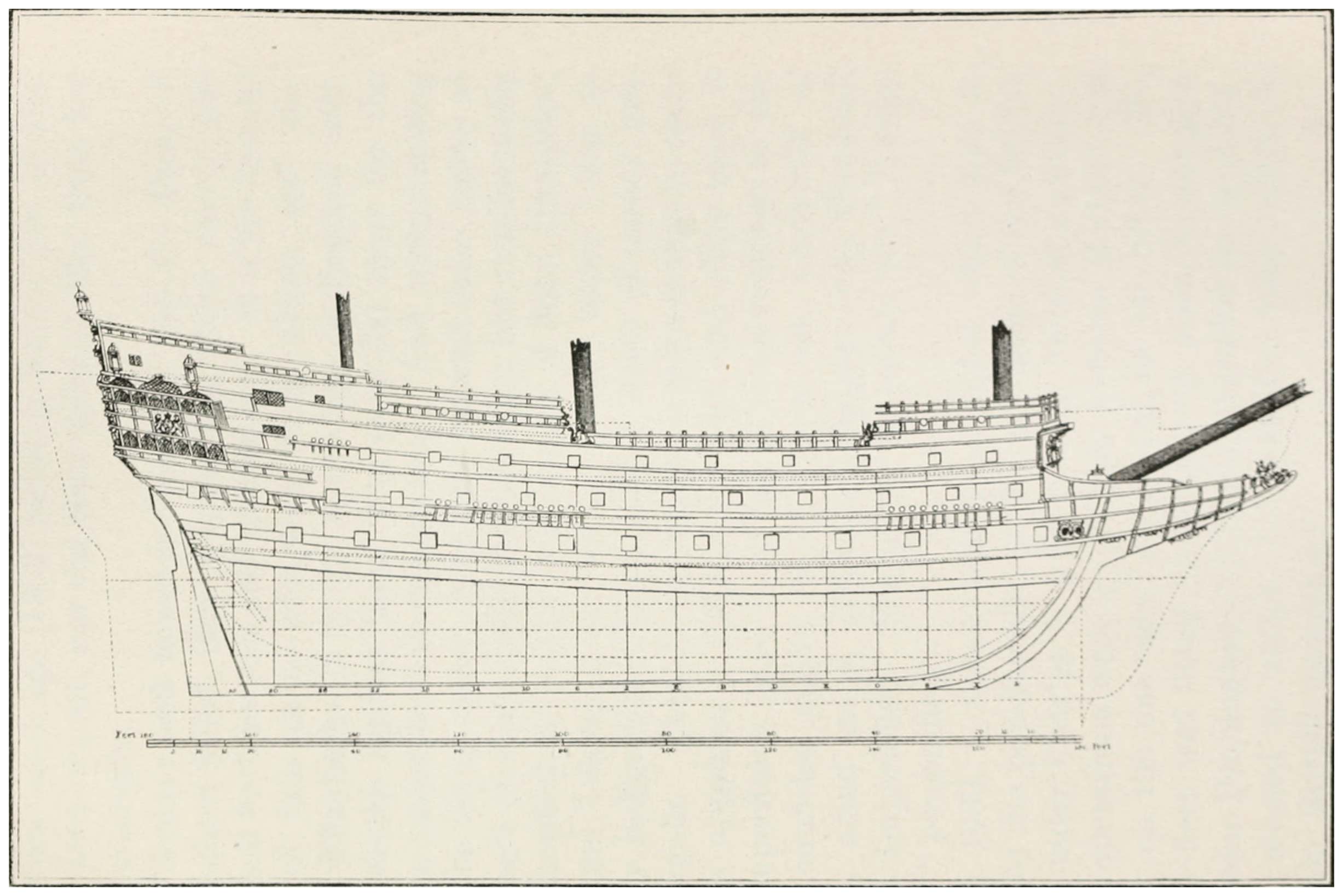

| PHINEAS PETT’S “ROYAL SOVEREIGN” | 71 |

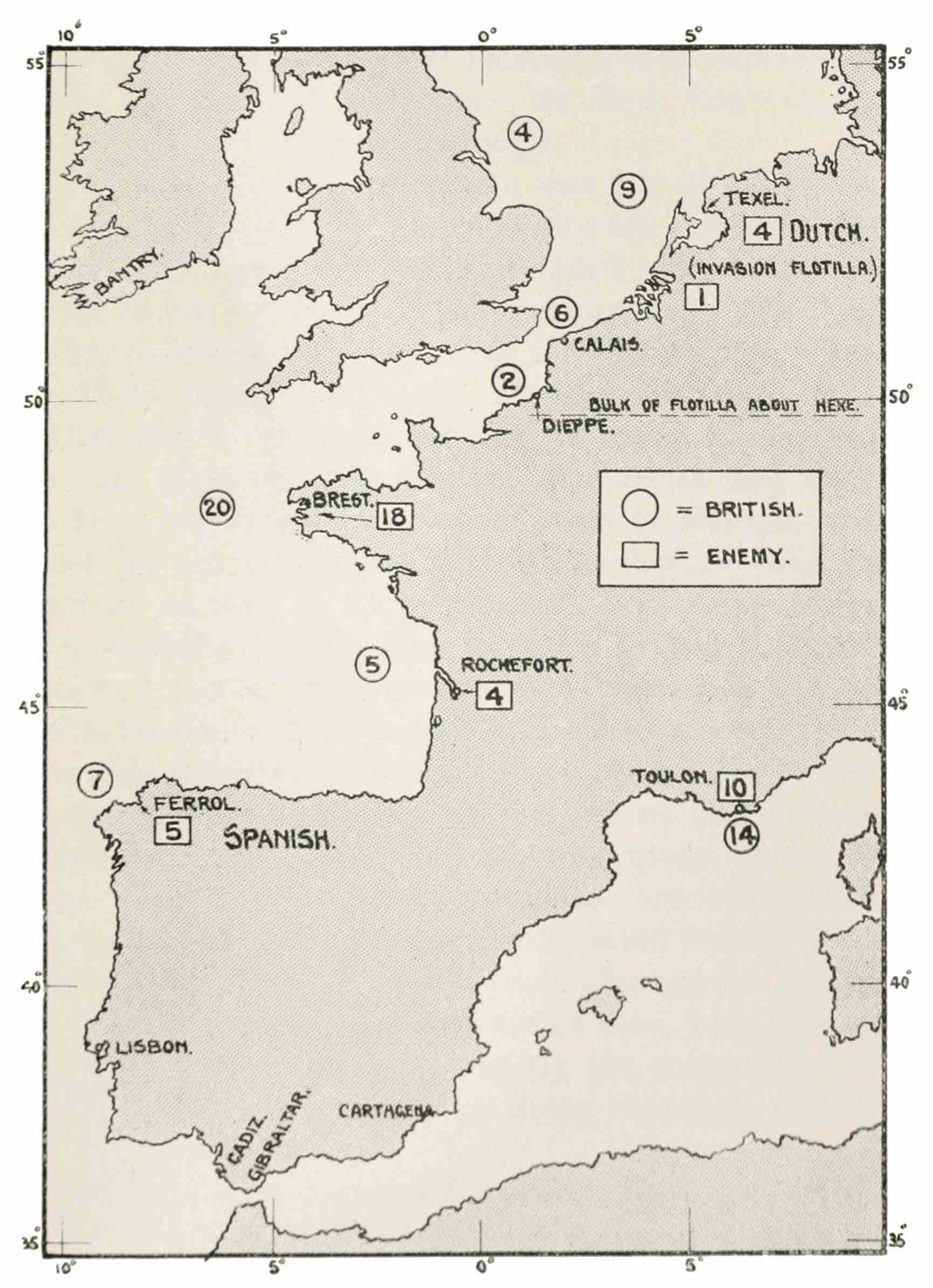

| POSITIONS OF THE FLEETS AT THE OUTBREAK OF WAR | 167 |

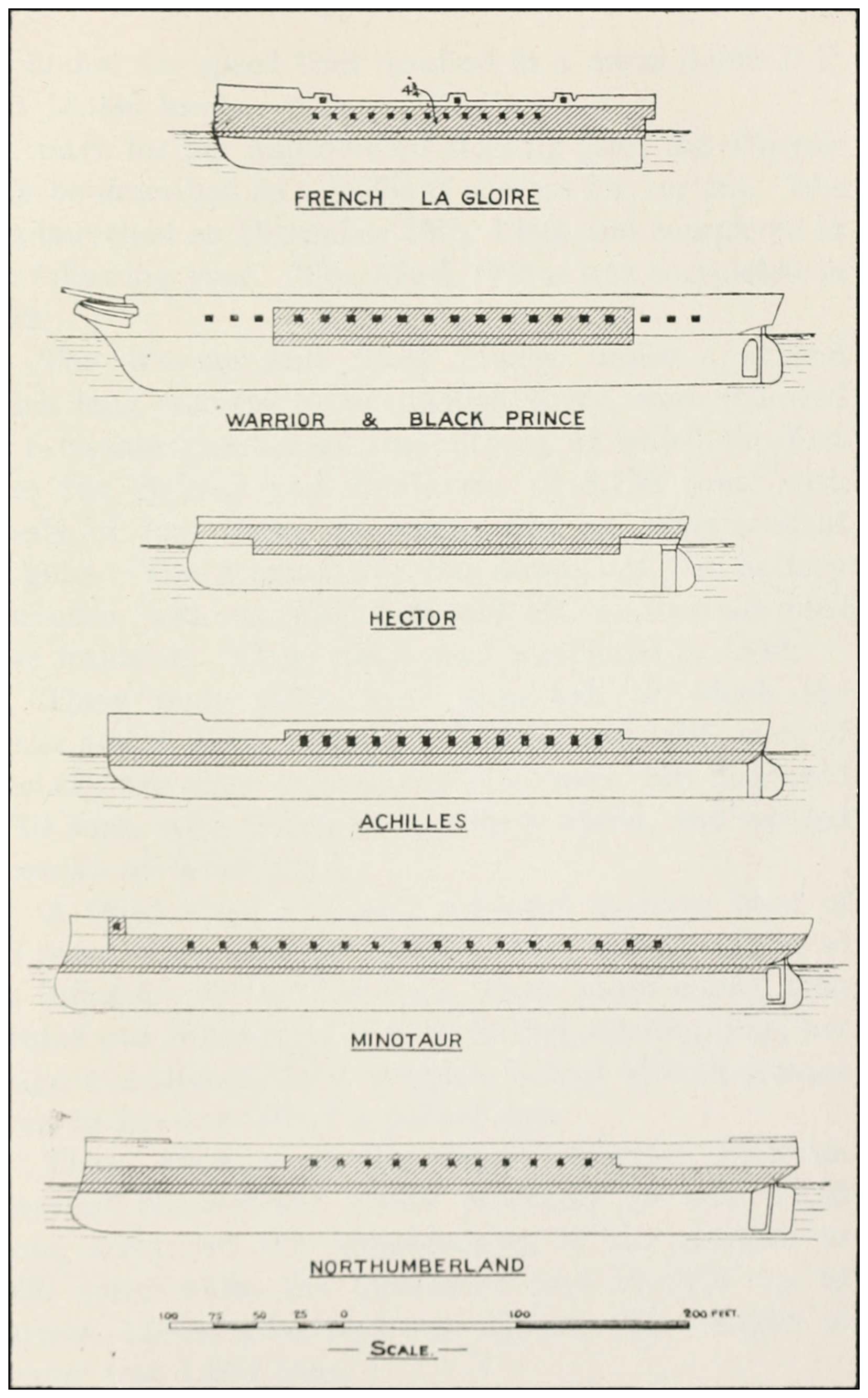

| EARLY BROADSIDE IRONCLADS | 255 |

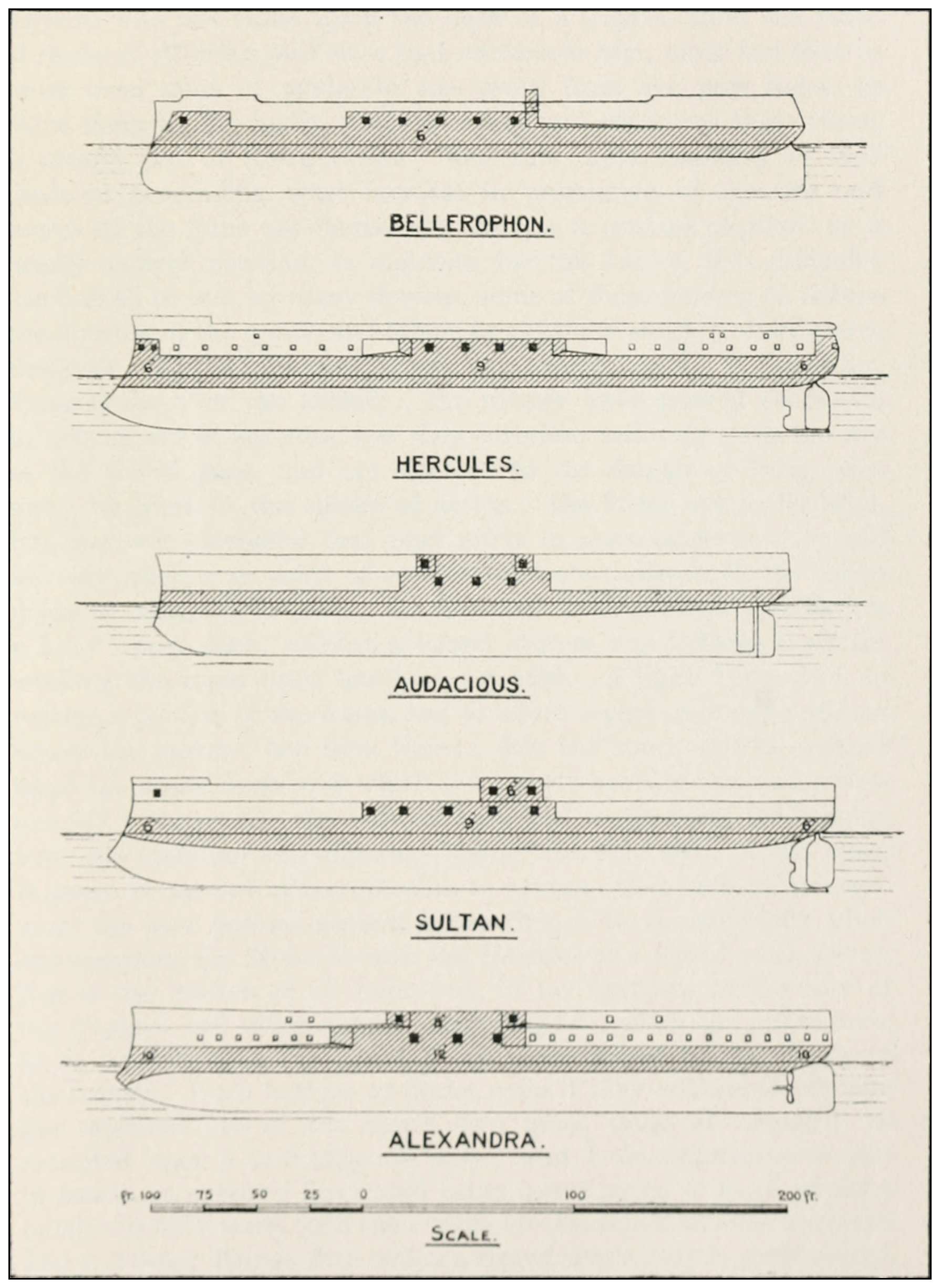

| REED ERA BROADSIDE SHIPS | 281 |

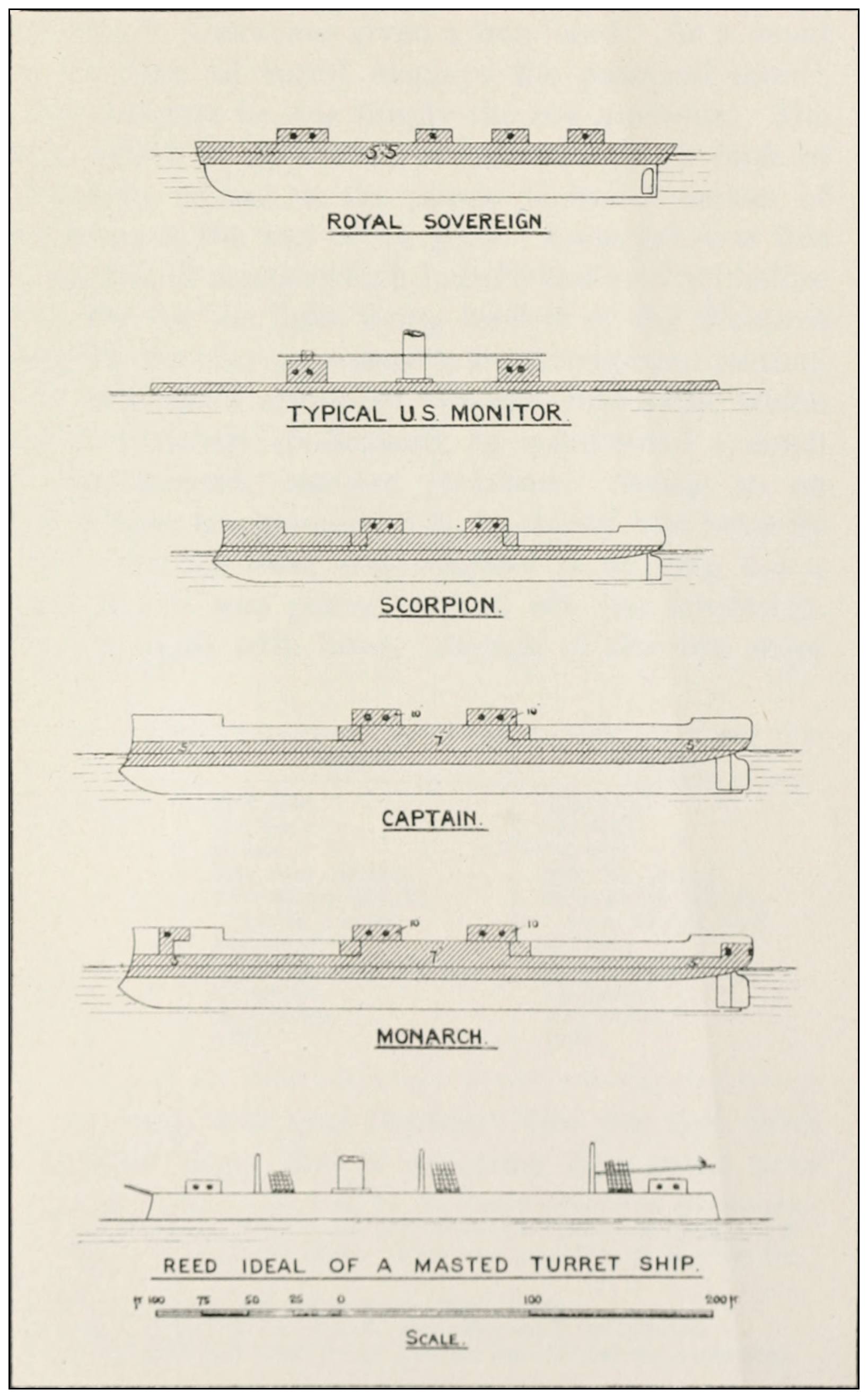

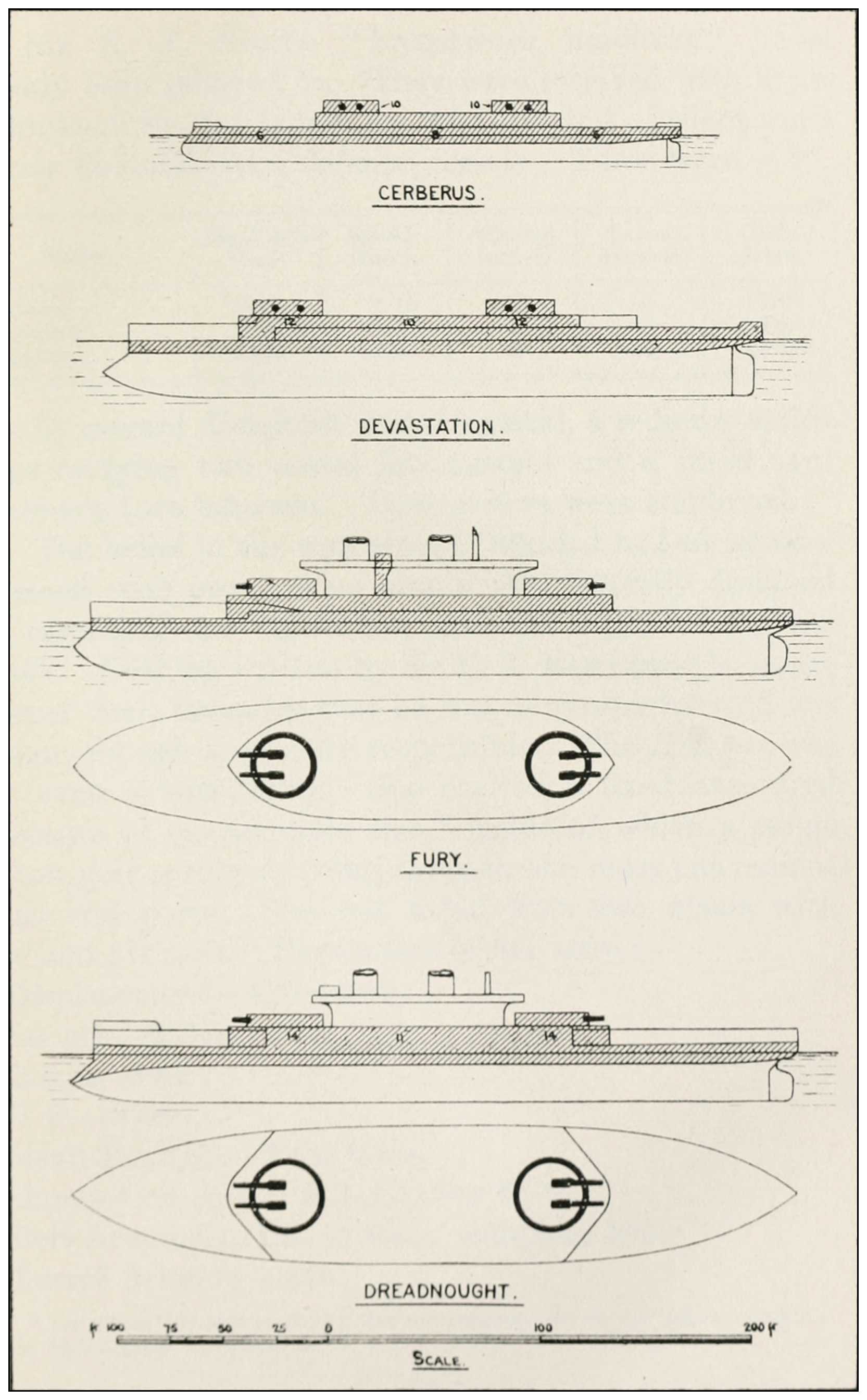

| REED ERA TURRET SHIPS | 285 |

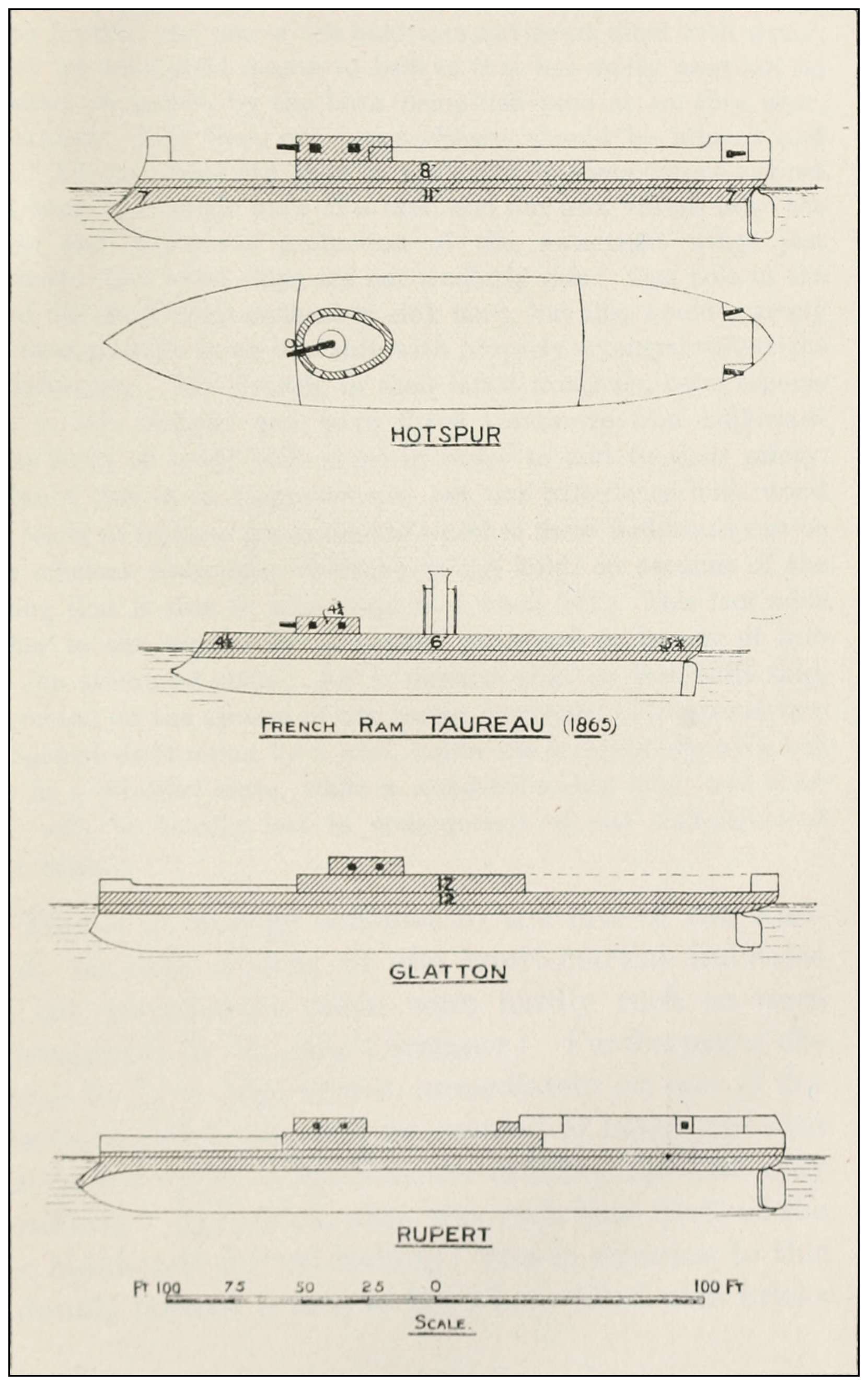

| RAMS OF THE REED ERA | 301 |

| BREASTWORK MONITORS | 305 |

1

The birth of British naval power is involved in considerable obscurity and a good deal of legend. The Phœnicians and the Romans have both been credited with introducing nautical ideas to these islands, but of the Phœnicians there is nothing but legend so far as any “British Navy” is concerned. That the Phœnicians voyaged here we know well enough, and a “British fleet” of the B.C. era may have existed, a fleet due to possible Phœnicians who, having visited these shores, remained in the land. Equally well it may be mythical.

Whatever share the ancient Britons may have had in the supposed commercial relations with Gaul, it is clear that no fleet as we understand a fleet existed in the days of Julius Cæsar. Later, while England was a Roman province, Roman fleets occasionally fought upon British waters against pirates and in connection with Roman revolutions, but they were ships of the ruling power.

Roman power passed away. Saxons invaded and remained; but having landed they became people of the land—not of the sea. Danes and other seafarers pilaged English shores much as they listed till Alfred the Great came to the throne.

2

Alfred has been called the “Father and Founder of the British Fleet.” It is customary and dramatic to suppose that Alfred was seized with the whole modern theory of “Sea Power” as a sudden inspiration—that “he recognised that invaders could only be kept off by defeating them on the sea.”

This is infinitely more pretty than accurate. To begin with, even at the beginning of the present Twentieth Century it was officially put on record that “while the British fleet could prevent invasion, it could not guarantee immunity from small raids on our great length of coast line.” In Alfred’s day, one mile was more than what twenty are now; messages took as many days to deliver as they now do minutes, and the “raid” was the only kind of over-sea war to be waged. It is altogether chimerical to imagine that Alfred “thought things out” on the lines of a modern naval theorist.

In actual fact,1 what happened was that Alfred engaged in a naval fight in the year 875, somewhere on the South Coast. There is little or no evidence to show where, though near Wareham is the most likely locality.

In 877 something perhaps happened to the Danes at Swanage, but the account in Asser is an interpolated one, and even so suggests shipwreck rather than a battle.

In 882 (possibly 881) two Danish ships sank: “the rest” (number not recorded) surrendered later on.

In 884 occurred the battle of the Stour. Here the Saxon fleet secured a preliminary success, in which thirteen Danish ships were captured. This may or5 may not have been part of an ambush—at any rate the final result was the annihilation of King Alfred’s fleet.

In 896 occurred the alleged naval reform so often alluded to as the “birth of the British Navy”—those ships supposed to have been designed by Alfred, which according to Asser2 were “full nigh twice as long as the others ... shapen neither like Frisian nor the Danish, but so as it seemed to him that they would be most efficient.”

Around these “early Dreadnoughts” much has been weaved, but there is no evidence acceptable to the best modern historians that Alfred really built any such ships—they tend to reject the entire theory.

The actual facts of that “naval battle of the Solent” in 897 from which the history of our navy is popularly alleged to date, appear to be as follows:

There were nine of King Alfred’s ships, manned by Frisian pirates, who were practically Danes. These nine encountered three Danish vessels in a land-locked harbour—probably Brading—and all of them ran aground, the Danish ships being in the middle between two Saxon divisions. A land fight ensued, till, the tide rising, the Danish ships, which were of lighter draught than the Saxon vessels, floated. The Danes then sailed away, but in doing so two of them were wrecked.

All the rest of the story seems to be purely legendary. Our real “island story”—as events during the next few hundred years following Alfred clearly indicate—is not that of a people born to the sea; but the story of a people forced thereto by circumstances and the need of self-preservation.

6

It is a very unromantic beginning. There is a strange analogy between it and the beginning in later days of the Sea Power of the other “Island Empire”—Japan. Japan to-day seeks—as we for centuries have sought—for an historical sequence of the “sea spirit” and all such things as an ideal islander should possess. Neither we nor they have ever understood or ever properly realised that it was the Continentals who long ago first saw that it was necessary to command the sea to attack the islanders. The more obvious contrary has always been assumed. It has never been held, or even suggested, that the Little Englander protesting against “bloated naval armaments,” so far from being a modern anachronism, an ultra-Radical or Socialist exotic, may really claim to be the true exponent of “the spirit of the Islanders” for all time. That is one reason why (excluding the mythical Minos of Crete) only two island-groups have ever loomed big in the world’s history.

When Wilhelm II of Germany said: “Unsere Zukunft liegt auf dem Wasser,” he uttered a far more profound truth than has ever been fully realised. Fleets came into being to attack Islanders with.

The Islanders saw the sea primarily as a protection existing between them and the enemy. To the Continental the sea was a road to, or obstacle between him and the enemy, only if the enemy filled it with ships. The Islanders have ever tended to trust to the existence of the sea itself as a defence, except in so far as they have been taught otherwise by individuals who realised the value of shipping. Those millions of British citizens who to-day are more or less torpid on the subject of naval defence are every whit as normal as7 those Germans who, in season and out, preach naval expansion.

The explanation of all this is probably to be found in the fact that the earliest warfare known either to Continentals or to Islanders was military warfare. The ship as at first employed was used entirely as a means of transport for reaching the enemy—first, presumably, against outlying islands near the coast, later for more over-sea expeditions.

Ideas of attack are earlier than ideas of defence, and the primary idea of defence went no further than the passive defensive. King Alfred, merely in realising the offensive defensive, did a far greater thing than any of the legendary exploits associated with his history. The idea was submerged many a time in the years that followed, but from time to time it appeared and found its ultimate fruition in the Royal Navy.

Yet still, the wonder is not that only two Island Empires have ever come into existence, but that any should have come into existence at all. The real history of King Alfred’s times is that the Continental Danes did much as they listed against the insular Saxons of England, till the need was demonstrated for an endeavour to meet the enemy on his own element.

In the subsequent reigns of Athelstan and Edmund, some naval expeditions took place. Under Edgar, the fleet reached its largest. Although the reputed number of 3,600 vessels is, of course, an exaggerated one, there was enough naval power at that time to secure peace.

This “navy” had, however, a very transient existence, because in the reign of Ethelred, who succeeded to the throne, it had practically ceased to exist, and an attempt was made to revive it. This attempt was so8 little successful that Danish ships had to be hired for naval purposes.

A charter of the time of Ethelred II exists which is considered by many to be the origin of that Ship Money which, hundreds of years later, was to cause so much trouble to England. Under this, the maintenance of the Navy was made a State charge on landowners, the whole of whom were assessed at the rate of producing one galley for every three hundred and ten hides of land that they possessed.

This view is disputed by some historians, who maintain that the charter is possibly a forgery, and that it is not very clear in any case. However, it does not appear to have produced any useful naval power.

That naval power was insufficient is abundantly clear from the ever increasing number of Danish settlements. In the St. Bride’s Day massacre, which was an attempt to kill off the leading Danes amongst the recent arrivals, further trouble arose; and in the year 1013, Swain, King of Denmark, made a large invasion of England, and in the year 1017, his son Canute ascended to the throne.

Under Canute, the need of a navy to protect the coast against Danish raids passed away. The bulk of the Danish ships were sent back to Denmark, forty vessels only being retained.

Once or twice during the reign of Canute successful naval expeditions were undertaken, but at the time of the King’s death the regular fleet consisted of only sixteen ships. Five years later, an establishment was fixed at thirty-two, and remained more or less at about that figure, till, in the reign of Edward the Confessor trouble was caused by Earl Godwin, who had created a species of fleet of his own. With a view to suppressing9 these a number of King’s ships were fitted out; but as the King and Godwin came to terms the fleet was not made use of.

Close following upon this came the Norman invasion, which of all the foolhardy enterprises ever embarked on by man was theoretically one of the most foolish. William’s intentions were perfectly well known. A certain “English fleet” existed, and there was nothing to prevent its expansion into a force easily able to annihilate the heterogeneous Norman flotilla.

How many ships and men William actually got together is a matter upon which the old chroniclers vary considerably. But he is supposed to have had with him some 696 ships3; and since his largest ships were not over twenty tons and most of them a great deal smaller, it is clear that they must have been crowded to excess and in poor condition to give battle against anything of the nature of a determined attack from an organised fleet.

No English fleet put in appearance, however. Harold had collected a large fleet at Sandwich, but after a while, for some unknown reason, it was dispersed, probably owing to the lateness of the season. The strength of the fleet collected, or why it was dispersed, are, however, immaterial issues; the fact of importance is that the fleet was “inadequate” because it failed to prevent the invasion. A neglected fleet entailed the destruction of the Saxon dominion.

10

William the Conqueror’s first act on landing was to burn all his ships—a proceeding useful enough in the way of preventing any of his followers retiring with their spoils, but inconvenient to him shortly after he became King of England. Fleets from Denmark and Norway raided the coasts, and, though the raiders were easily defeated on shore, the pressure from them was sufficient to cause William to set about recreating a navy, of which he made some use in the year 1071. In 1078 the Cinque Ports were established, five ports being granted certain rights in return for policing the Channel and supplying ships to the King as required. But the amount of naval power maintained was very small, both in the reign of William the First and his successors.

Not until the reign of Henry II was any appreciable attention paid to nautical matters. Larger ships than heretofore were built, as we assume from records of the loss of one alleged to carry 300 men. It was Henry II who first claimed the “Sovereignty of the British Seas” and enacted the Assize of Arms whereby no ship or timber for shipbuilding might be sold out of England.

When Richard I came to the throne in 1189, fired with ambition to proceed to the Crusades, he ordered all ports in his dominions to supply him with ships11 in proportion to their population. The majority of these ships came, however, from Acquitaine. The fleet thus collected is said to have consisted of nine large ships, 150 small vessels, thirty galleys, and a number of transports. The large ships, which have also been given as thirteen in number, were known at the time as “busses.” They appear to have been three-masters. The fleet sailed in eight divisions. This expedition to the Holy Land was the first important over-sea voyage ever participated in by English ships, the greatest distance heretofore traversed having been to Norway in the time of Canute. This making of a voyage into the unknown was, however, not quite so difficult as it might at first sight be supposed to be, because there is no doubt whatever that the compass was by then well-known and used. Records from 1150 and onwards exist which describe the compass of that period. A contemporary chronicler4 wrote of it:—

“This [polar] star does not move. They [the seamen] have an art which cannot deceive, by virtue of the manite, an ill brownish stone to which iron spontaneously adheres. They search for the right point, and when they have touched a needle on it, and fixed it to a bit of straw, they lay it on water, and the straw keeps it afloat. Then the point infallibly turns towards the star; and when the night is dark and gloomy, and neither star nor moon is visible, they set a light beside the needle, and they can be assured that the star is opposite to the point, and thereby the mariner is directed in his course. This is an art which cannot deceive.”

The compass would seem to have existed, so far as northern nations were concerned, about the time of William the Conqueror. Not till early in the Fourteenth Century did it assume the form in which we now know it, but its actual antiquity is considerably more.

12

In connection with this expedition to the Holy Land, Richard issued a Code of Naval Discipline, which has been described as the germ of our Articles of War. Under this Code if a man killed another on board ship, he was to be tied to the corpse and thrown into the sea. If the murder took place on shore, he was to be buried alive with the corpse. The penalty for drawing a knife on another man, or drawing blood from him in any manner was the loss of a hand. For “striking another,” the offender was plunged three times into the sea. For reviling or insulting another man, compensation of an ounce of silver to the aggrieved one was awarded. The punishment for theft was to shave the head of the thief, pour boiling pitch upon it and then feather him. This was done as a mark of recognition. The subsequent punishment was to maroon a man upon the first land touched. Severe penalties were imposed on the mariners and servants for gambling.

Of these punishments the two most interesting are those for theft and the punishment of “ducking.” This last was presumably keel-hauling, a punishment which survived well into the Nelson era. It is to be found described in the pages of Marryat. It consisted in drawing the offender by ropes underneath the bottom of the ship. As his body was thus scraped along the ship’s hull, the punishment was at all times severe; but in later days, as ships grew larger and of deeper draught, it became infinitely more cruel and heavy than in the days when it was first instituted.

The severe penalty for theft is to be noted on account of the fact that, even in the early times, theft, as now, was and is recognised as a far more serious offence on ship board than it is on shore—the reason being the greater facilities that a ship affords for theft.

15

On his way to the Holy Land, Richard had a dispute at Sicily with the King of France, out of which he increased his fleet somewhat. Leaving Sicily, somewhere between Cyprus and Acre he encountered a very large Saracen ship, of the battle with which very picturesque and highly coloured accounts exist. There is no doubt that the ship was something a great deal larger than anything the English had ever seen heretofore, although the crew of 1,500 men with which she is credited by the chroniclers is undoubtedly an exaggeration.

The ship carried an armament of Greek fire and “serpents.” The exact composition of Greek fire is unknown. It was invented by the Byzantines, who by means of it succeeded in keeping their enemies at bay for a very long time. It was a mixture of chemicals which, upon being squirted at the enemy from tubes, took fire, and could only be put out by sand or vinegar. “Serpents” were apparently some variation of Greek fire of a minor order, discharged by catapults.

In the first part of the attack the English fleet was able to make no impression upon the enemy, as her high sides and the Greek fire rendered boarding impossible. Not until King Richard had exhilarated his fleet by informing them that if the galley escaped they “should be crucified or put to extreme torture,” was any progress made. After that, according to the contemporary account, some of the English jumped overboard and succeeded in fastening ropes to the rudder of the Saracen ship, “steering her as they pleased.” They then obtained a footing on board, but16 were subsequently driven back. As a last resource King Richard formed his galleys into line and rammed the ship, which afterwards sank.

The relation of Richard’s successor, King John, to the British Navy, is one of some peculiar interest. More than any king before him he appears to have appreciated the importance of naval power, and naval matters received more attention than heretofore. In the days of King John the crews of ships appropriated for the King’s service were properly provisioned with wine and food, and there are also records of pensions for wounds, one of the earliest being that of Alan le Walleis, who received a pension of sixpence a day for the loss of his hand.5

King John is popularly credited with having made the first claim to the “Sovereignty of the Seas” and of having enacted that all foreign vessels upon sighting an English one were to strike their flags to her, and that if they did not that it was lawful to destroy them. The authenticity of this is, however, very doubtful; and it is more probable that, on account of various naval regulations which first appeared in the reign of King John, this particular regulation was fathered upon him at a later date with the view to giving it an historical precedent.

In the reign of King John the “Laws of Oleron” seem to have first appeared, but it is not at all clear that they had any specific connection with England. They appear rather to have been of a general European nature. The gist of the forty-seven articles of the “Laws of Oleron,” of which the precise date of promulgation cannot be ascertained, is as follows:—5

17

“By the first article, if a vessel arrived at Bordeaux, Rouen, or any other similar place, and was there freighted for Scotland, or any other foreign country, and was in want of stores or provisions, the master was not permitted to sell the vessel, but he might with the advice of his crew raise money by pledging any part of her tackle or furniture.

“If a vessel was wind or weather bound, the master, when a change occurred, was to consult his crew, saying to them, “Gentlemen, what think you of this wind?” and to be guided by the majority whether he should put to sea. If he did not do this, and any misfortune happened, he was to make good the damage.

“If a seaman sustained any hurt through drunkenness or quarrelling, the master was not bound to provide for his cure, but might turn him out of his ship; if, however, the injury occurred in the service of his ship, he was to be cured at the cost of the said ship. A sick sailor was to be sent on shore, and a lodging, candles, and one of the ship’s boys, or a nurse provided for him, with the same allowance of provisions as he would have received on board. In case of danger in a storm, the master might, with the consent of the merchants on board, lighten the ship by throwing part of the cargo overboard; and if they did not consent, or objected to his doing so, he was not to risk the vessel but to act as he thought proper; on their arrival in port, he and the third part of the crew were to make oath that it was done for the preservation of the vessel; and the loss was to be borne equally by the merchants. A similar proceeding was to be adopted before the mast or cables were cut away.

“Before goods were shipped the master was to satisfy the merchants of the strength of his ropes and slings; but if he did not do so, or they requested him to repair them and a cask were stove, the master was to make it good.

“In cases of difference between a master and one of his crew, the man was to be denied his mess allowance thrice, before he was turned out of the ship, or discharged; and if the man offered reasonable satisfaction in the presence of the crew, and the master persisted in discharging him, the sailor might follow the ship to her place of destination, and demand the same wages as if he had not been sent ashore.

18

“In case of a collision by a ship undersail running on board one at anchor, owing to bad steering, if the former were damaged, the cost was to be equally divided; the master and crew of the latter making oath that the collision was accidental. The reason for this law was, it is said, ‘that an old decayed vessel might not purposely be put in the way of a better.’ It was specially provided that all anchors ought to be indicated by buoys or ‘anchor-marks.’

“Mariners of Brittany were entitled only to one meal a day, because they had beverage going and coming; but those of Normandy were to have two meals, because they had only water as the ship’s allowance. As soon as the ship arrived in a wine country, the master was, however, to procure them wine.

“Several regulations occur respecting the seamen’s wages, which show that they were sometimes paid by a share of the freight. On arriving at Bordeaux or any other place, two of the crew might go on shore and take with them one meal of such victuals as were on board, and a proportion of bread, but no drink; and they were to return in sufficient time to prevent their master losing the tide. If a pilot from ignorance or otherwise failed to conduct a ship in safety, and the merchants sustained any damage, he was to make full satisfaction if he had the means to; if not, he was to lose his head; and, if the master or any one of the mariners cut off his head, they were not bound to answer for it; but, before they had recourse to so strong a measure, ‘they must be sure he had not wherewith to make satisfaction.’

“Two articles of the code prove, that from an ‘accursed custom’ in some places, by which the third or fourth part of ships that were lost belonged to the lord of the place—the pilots, to ingratiate themselves with these nobles, ‘like faithless and treacherous villains,’ purposely ran the vessel on the rocks. It was therefore enacted that the said lords, and all others assisting in plundering the wreck, shall be accursed and excommunicated, and punished as robbers and thieves; that ‘all false and treacherous pilots should suffer a most rigorous and merciless death,’ and be suspended to high gibbets near the spot, which gibbets were to remain as an example in succeeding ages. The barbarous lords were to be tied to a post in the middle of their own houses, and, being set on fire at the four corners, all were to be burned together; the walls19 demolished, its site converted into a marketplace for the sale only of hogs and swine, and all their goods to be confiscated to the use of the aggrieved parties.

“Such of the cargoes as floated ashore were to be taken care of for a year or more; and, if not then claimed, they were to be sold by the lord, and the proceeds distributed among the poor, in marriage portions to poor maids and other charitable uses. If, as often happened, ‘people more barbarous, cruel, and inhuman than mad dogs,’ murdered shipwrecked persons, they were to be plunged into the sea till they were half-dead, and then drawn out and stoned to death.”

Those laws, unconnected though they appear to be with strictly naval matters, are none the less of extreme interest as indicating the establishment of “customs of the sea,” and the consequent segregation of a “sailor class.” It has ever to be kept very clearly in mind that there was no such thing as a “Navy” as we understand it in these days. When ships were required for war purposes they were hired, just as waggons may be hired by the Army to-day; nor did the mariners count for much more than horses. The “Laws of Oleron,” however, gave them a certain general status which they had not possessed before; and the regulations of John as to providing for those engaged upon the King’s service—though they in no way constituted a Royal Navy—played their part many years later in making a Royal Navy possible, or, perhaps, it may be said, “necessary.” Necessity has ever been the principal driving force in the naval history of England.

To resume. The limitations of the powers of the master (i.e. captain) in these “Laws of Oleron” deserve special attention. “Gentlemen, what think you of this wind?” from the captain to his crew would be considered “democracy” carried to extreme and extravagant limits in the present day; in the days when it was20 promulgated as “the rule” it was surely stranger still! Little wonder that seamen at an early stage segregated from the ordinary body of citizens and became, as described by Clarendon in his “History of the Rebellion” a few hundred years later, when he wrote:—

“The seamen are a nation by themselves, a humorous and fantastic people, fierce and rude and resolute in whatsoever they resolve or are inclined to, but unsteady and inconstant in pursuing it, and jealous of those to-morrow by whom they are governed to-day.”

To this, to the earlier things that produced it, those who will may trace the extreme rigour of naval discipline and naval punishments, as compared with contemporaneous shore punishments at any given time, and the extraordinary difference at present existing between the American and European navies. The difference is usually explained on the circumstance that “Europe is Europe, and America, America.” But “differences” having their origin in the “Laws of Oleron” may play a greater part than is generally allowed.

The year 1213 saw the Battle of Damme. This was the first real naval battle between the French and English. The King of France had collected a fleet of some “seventeen hundred ships” for the invasion of England, but having been forbidden to do so by the Pope’s Legate, he decided to use his force against Flanders. This Armada was surprised and totally destroyed by King John’s fleet.

After the death of John the nautical element in England declared for Henry III, son of John, and against Prince Louis of France, who had been invited to the throne of England by the barons. Out of this came the battle of Sandwich, 1217, where Hubert de21 Burgh put into practice, though in different form, those principles first said to have been evolved by Alfred the Great—namely, to attack with an assured and complete superiority.

Every English ship took on board a large quantity of quick-lime and sailed to meet the French, who were commanded by Eustace the Monk. De Burgh manœuvred for the weather gauge. Having gained it, the English ships came down upon the French with the wind, the quick-lime blowing before them, and so secured a complete victory over the tortured and blinded French. This is the first recorded instance of anything that may be described as “tactics” in Northern waters.

The long reign of Henry III saw little of interest in connection with nautical matters. But towards the end of Henry’s reign a private quarrel between English and Norman ships, both seeking fresh water off the Coast of Bayonne, had momentous consequences. The Normans, incensed over the quarrel, captured a couple of English ships and hanged the crew on the yards interspersed with an equal number of dead dogs. Some English retaliated in a similar fashion on such Normans as they could lay hands on, and, retaliation succeeding retaliation, it came about that in the reign of Edward I, though England and France were still nominally at peace, the entire mercantile fleets of both were engaged in hanging each other, over what was originally a private quarrel as to who should be first to draw water at a well.

Ultimately the decision appears to have been come by “to fight it out.” Irish and Dutch ships assisted22 the English. Flemish and Genoese ships assisted the Normans and French. The English to the number of 60 were under Sir Robert Tiptoft. The number of the enemy is placed at 200, though it was probably considerably less. In the battle that ensued the Norman and French fleets were annihilated.

This battle, even more than others of the period, cannot be considered as one of the battles of “the British fleet.” It is merely a conflict between one clique of pirates and traders against another clique. But it is important on account of the light that it sheds on a good deal of subsequent history; for the fashion thus started lasted in one way and another for two or three hundred years.

Nor were these disputes always international. Four years later than the fight recorded above, in 1297, the King wished to invade Flanders with an army of 50,000 men. The Cinque Ports being unable to supply the requisite number of ships to transport this army, requisitions were also made at Yarmouth. Bad blood soon arose between the two divisions, with the result that they attacked each other. Thirty of the Yarmouth ships with their crews were destroyed and the expedition greatly hampered thereby.

Two events of importance in British naval history happened in the reign of Edward I. The first of these, which took place about the year 1300, arose out of acts of piracy on foreigners, to which English ships were greatly addicted at that time. In an appeal made to Edward by those Continentals who had suffered most from these depredations, the King was addressed as “Lord of the Sea.” This was a definite recognition of that23 sea claim first formulated by Henry II and which was afterwards to lead to so much fighting and bloodshed.

The second event was the granting of the first recorded “Letters of Marque” in the year 1295. These were granted to a French merchant who had been taking a cargo of fruit from Spain to England and had been robbed by the Portuguese. He was granted a five year license to attack the Portuguese in order to recoup his loss.

In the reign of Edward II the only naval event of interest is, that when the Queen came from abroad and joined those who were fighting against the King, the nautical element sided with her.

The reign of Edward III saw some stirring phases in English history. With a view to carrying on his war against France, Edward bestowed considerable attention on naval matters, and in the year 1338, he got together a fleet stated to have consisted of 500 vessels. These were used as transports to convey the Army to France, and are estimated to have carried on the average about eighty men each.

Meanwhile, the French had also got together a fleet of about equal size, and no sooner had the English expedition reached the shores of France than the whole of the south coast of England was subjected to a series of French raids. Southampton, Plymouth and the Cinque Ports were sacked and burned with practical impunity. These raids continued during 1338 and 1339; the bulk of the English fleet still lying idle on transport service at Edward’s base in Flanders. A certain number of ships had been sent back, but most of these had been as hastily sent on to Scotland, where their services24 had been urgently needed. Matters in the Channel culminated with the capture of the two largest English ships of the time. A fleet of small vessels hastily fitted out at the Cinque Ports succeeded in destroying Boulogne and a number of ships that lay there, but generally speaking the French had matters very much their own way on the sea.

Towards the end of 1339, Edward and his expedition returned to England to refit, with a view to preparing for a fresh invasion of France during the following summer.

As Edward was about to embark, he learned that the French King had got together an enormous fleet at Sluys. After collecting some additional vessels, bringing the total number of ships up to 250 or thereabouts, Edward took command and sailed for Sluys, at which port he found the French fleet. He localised the French on Friday, July 3rd, but it was not until the next day that the battle took place.

The recorded number of the enemy in all these early sea fights requires to be accepted with caution. For what it is worth the number of French ships has been given at 400 vessels, each carrying 100 men. The French, as on a later occasion they did on the Nile, lay on the defensive at the mouth of the harbour, the ships being lashed together by cables. Their boats, filled with stones, had been hoisted to the mast-heads. In the van of their fleet lay the Christopher, Edward, and various other “King’s ships,” which they captured in the previous year.

The English took the offensive, and in doing so manœuvred to have the sun behind them. Then, with their leading ships crowded with archers they bore27 down upon the main French division and grappled with them. The battle, which lasted right throughout the night, was fought with unexampled fury, and for a long time remained undecisive, considerable havoc being wrought by the French with the then novel idea of dropping large stones from aloft. The combatants, however, were so mixed up that it is doubtful whether the French did not kill as many of their own number as of the enemy; whereas, on the other side, the use of English archers who were noted marksmen told only against those at whom the arrows were directed. Furthermore, the English had the tactical advantage of throwing the whole of their force on a portion of the enemy, whom they ultimately totally destroyed.

This Battle of Sluys took place in 1340. In 1346, after various truces, the English again attacked France in force, and the result was the Battle of Cressy. A side issue of this was the historic siege of Calais, which held out for about twelve months. 738 ships and 14,956 men are said to have been employed in the sea blockade.

Up to this time the principal English ship had been a galley, i.e., essentially a row boat. About the year 1350 the galley began to disappear as a capital ship, and the galleon, with sail as its main motive power, took its place. Also a new enemy appeared; for at that time England first came into serious conflict with Spain.

To a certain extent the galleon was to the fleets of the Mid-Fourteenth Century much what the ironclad was to the last quarter of the Nineteenth Century, or “Dreadnoughts” at the end of the first decade of the Twentieth Century.

28

The introduction of this type of vessel came about as follows:—

A fleet of Castillian galleons, bound for Flanders, whiled away the monotony of its trip by acts of piracy against all English ships that it met. It reached Sluys without interference. Here it loaded up with rich cargoes and prepared to return to Spain. The English meanwhile collected a fleet to intercept it, this fleet being in command of King Edward himself, who selected the “cog Thomas” as his flagship.

The English tactics would seem to have been carefully thought out beforehand. The Castillian ships were known to be of relatively vast size and more or less unassailable except by boarding. The result was that when at length they appeared, the English charged their ships into them, sinking most of their own ships in the impact, sprang aboard and carried the enemy by boarding. The leading figure on the English side was a German body-servant of the name of Hannekin, who distinguished himself just at the crisis of the battle by leaping on board a Castillian ship and cutting the halyards. Otherwise the result of the battle might have been different, because the Castillians, when about half only of the English ships were grappled with them, hoisted their sails, with the object of sailing away and destroying the enemy in detail. Hannekin’s perception of this intention frustrated the attempt.

The advantages of the galleons (or carracks as they were then called), must have been rendered obvious in this battle of “Les Espagnols-sur-Mer,” as immediately afterwards ships on the models of those captured began to be hired for English purposes.

29

Concurrent, however, with this building of a larger type of ship, a decline of naval power began; and ten years later, English shipping was in such a parlous state that orders were issued to the effect that should any of the Cinque Ports be attacked from the sea, any ships there were to be hauled up on land, as far away from the water as possible, in order to preserve them.

In the French War of 1369, almost the first act of the French fleet was to sack and burn Portsmouth without encountering any naval opposition.

In 1372 some sort of English fleet was collected, and under the Earl of Pembroke sent to relieve La Rochelle, which was then besieged by the French and Spanish. The Spanish ships of that period had improved on those of twenty years before, to the extent that (according to Froissart), some carried guns. In any case they proved completely superior to the English, whose entire fleet was captured or sunk.

This remarkable and startling difference is only to be accounted for by the difference in the naval policy of the two periods. In the early years of Edward III’s reign, when a fleet was required it was in an efficient state, and when it encountered the enemy, it was used by those who had obviously thought out the best means of making the most of the material available. In the latter stage, there was neither efficiency nor purpose. The result was annihilation.

How far the introduction of cannon on shipboard contributed to this result it is difficult to say exactly. In so far as it may have, the blame rests with the English, who were perfectly familiar with cannon at that time. If, therefore, the very crude stone-throwing cannon of those days had any particular advantages30 over the stone-throwing catapults previously employed, failure to fit them is merely a further proof of the inefficiency of those responsible for naval matters in the closing years of Edward III’s reign. Probably, however, the cannon contributed little to the result of La Rochelle, for, like all battles of the era, it was a matter of boarding—of “land fighting on the water.”

The reign of Richard II saw England practically without any naval power at all. The French and Spaniards raided the Channel without interference worth mention. Once or twice retaliatory private expeditions were made upon the French coast; but speaking generally the French and Spaniards had matters entirely their own way, and the latter penetrated the Thames so far as Gravesend.

In the year 1380, an English army was sent over to France, but this, as Calais was British, was a simple operation, and although two years later ships were collected for naval purposes, English sea impotence remained as conspicuous as ever. In 1385, when a French armada was collected at Sluys for the avowed purpose of invading England on a large scale, no attempt whatever seems to have been made to meet this with another fleet. Fortunately for England, delays of one kind and another led to the French scheme of invasion being abandoned.

Under Henry IV, matters remained much the same, until in the summer of 1407, off the coast of Essex, the King, who was voyaging with five ships, was attacked by French privateers, which succeeded in capturing all except the Royal vessel.

This led to the organisation of a “fleet” and a successful campaign against the privateers. The necessity33 of Sea Power began to be realised again, and this so far bore fruit that in the reign of Henry V no less than 1,500 ships were (it is said) collected in the Solent, for an invasion of France. But since some of these were hired from the Dutch and as every English vessel of over twenty tons was requisitioned by the King, the large number got together does not necessarily indicate the existence of any very great amount of naval power. This fleet, however, indicated a revival of sea usage.

In 1417, large ships known as “Dromons” were built at Southampton, and bought for the Crown, but these were more of the nature of “Royal Yachts” than warships. The principal British naval base at and about this period was at Calais, of which, at the time of the War of the Roses, the Earl of Warwick was the governor.

The first act of the Regency of Henry VI was to sell by auction such ships as had been bought for the Crown under Henry V. The duty of keeping the Channel free from pirates was handed over to London merchants, who were paid a lump sum to do this, but did not do it at all effectively.

Edward IV made some use of a Fleet to secure his accession, or later restoration. Richard III would seem to have realised the utility of a Fleet, and during his short reign he did his best to begin a revival of “the Navy” by buying some ships, which, however, he hired out to merchants for trade purposes; and so, at the critical moment, he had apparently nothing available to meet the mild over-sea expedition of Henry of Richmond. So—right up to comparatively recent times—there was never any Royal Navy in the proper meaning34 of the word, nor even any organised attempt to create an equivalent, except on the part of those two Kings who we are always told were the worst Kings England ever had—John and Richard III. Outside these two, there is not the remotest evidence that anyone ever dreamed of “naval power,” “sea power,” or anything of the sort, till Henry VII became King of England, and founded the British Navy on the entirely unromantic principle that it was a financial economy.

Such was the real and prosaic birth of the British Navy in relatively recent times. It was made equally prosaic in 1910 by Lord Charles Beresford, when he said, “Battleships are cheaper than war.”

There is actually no poetry about the British Navy. There never has been—it will be all the better for us if there never is. It is merely a business-like institution founded to secure these islands from foreign invasion. Dibden in his own day, Kipling in ours, have done their best to put in the poetry. It has been pretty and nice and splendid. But over and above it all I put the words of a stoker whose name I never knew, “It’s just this—do your blanky job!”

That is the real British Navy. Henry VII did not create this watchword, nor anyone else, except perhaps Nelson.

35

That Henry VII assimilated the lesson of the utility of naval power is abundantly clear. Henry VII it was who first established a regular navy as we now understand it. Previous to his reign, ships were requisitioned as required for war purposes, and, the war being over, reverted to the mercantile service. The liability of the Cinque Ports to provide ships when called upon constituted a species of navy, and certain ships were specially held as “Royal ships” for use as required, but under Henry ships primarily designed for fighting purposes appeared. The first of these ships was a vessel generally spoken of as the “Great Harry,” though her real name seems to have been The Regent, built in 1485. Incidentally this ship remained afloat till 1553, when she was burned by accident. She has been called “the first ship of the Royal Navy”; and though her right to the honour has been contested, she appears fully entitled to it. The real founder of the Navy as we understand a navy to-day was Henry VII.

Another important event of this reign is that during it the first dry dock was built at Portsmouth. Up till then there had been no facilities for the underwater repair of ships other than the primitive method of running them on to the mud and working on them at36 low tide. While ships were small this was not a matter of much moment, but directly larger vessels began to be built, it meant that efficient overhauls were extremely difficult, if not impossible.

Yet another step that had far reaching results was the granting of a bounty to all who built ships of over 120 tons. This bounty, which was “per ton” and on a sliding scale, made the building of large private ships more profitable and less risky than it had been before, and so assisted in the creation of an important auxiliary navy as complement to the Royal Navy.

The bounty system did more, however, than encourage the building of large private ships. The loose method of computing tonnage already referred to, became more elastic still when a bounty was at stake; and even looser when questions of the ship being hired per ton for State purposes was at issue. Henry VII, who was nothing if not economical, felt the pinch; the more so, as just about this time Continentals with ships for hire became alarmingly scarce. Something very like a “corner in ships” was created by English merchants.

Henry VII was thus, by circumstances beyond his own control, forced into creating a permanent navy in self defence. He died with a “navy” of eighteen ships, of which, however, only two were genuinely entitled to be called “H.M.S.” He had to hire the others!

This foundation of the “regular navy” is not at all romantic. But it is how a regular navy came to be founded—by force of circumstances. Henry VII, “founder of the Royal Navy,” undoubtedly realized clearer than any of his predecessors for many a hundred37 years the meaning of naval power. But—his passion for economy and the advantage taken by such of his subjects as had ships available when hired ships were scarce, had probably a deal more to do with the institution of a regular navy than any preconceived ideas. In two words—“Circumstances compelled.” And that is how things stood when Henry VIII came to the throne.

The nominal permanent naval power established by Henry VII consisted of fifty-seven ships, and the crew of each was twenty-one men and a boy, so that the Great Harry, which must have required a considerably larger crew, would seem to have been an experimental vessel. The actual force, however, was but two fighting ships proper.

Under Henry VIII, however, the policy of monster ships was vigorously upheld, and one large ship built in the early years of his reign—the Sovereign—was reputed to be “the largest ship in Europe.” In 1512 the King reviewed at Portsmouth “twenty-five ships of great burthen,” which had been collected in view of hostilities with France. These ships having been joined by others, and amounting to a fleet of forty-four sail, encountered a French fleet of thirty-nine somewhere off the coast of Brittany.

This particular battle is mainly noteworthy owing to the fact that the two flagships grappled, and while in this position one of them caught fire. The flames being communicated to the other, both blew up. This catastrophe so appalled the two sides that they abandoned the battle by mutual consent; from which it is to be presumed that the nautical mind of the day had,38 till then, little realised that risks were run by carrying explosives.

The English, however, were less impressed by the catastrophe than the enemy, since next day they rallied and captured or sank most of the still panic-stricken French ships.

Henry replaced the lost flagship by a still larger ship, the Grace de Dieu, a two-decker with the lofty poop and forecastle of the period. She was about 1,000 tons. Tonnage, however, was so loosely calculated in those days that measurements are excessively approximate.

When first cannon were introduced, they were (as previously remarked) merely a substitute for the old-fashioned catapults, and discharged stones for some time till more suitable projectiles were evolved. Like the catapults they were placed on the poop or forecastle, as portholes had not then been introduced. These were invented by a Frenchman, one Descharges, of Brest. By means of portholes it was possible to mount guns on the main deck and so increase their numbers.

Although the earliest portholes were merely small circular holes which did not allow of any training, and though the idea of them was probably directly derived from the loopholes in castle walls, the influence of the porthole on naval architecture was soon very great indeed. By means of this device a new relation between size and power was established, hence the “big displacements” which began to appear at this time. The hole for a gun muzzle to protrude through, quickly became an aperture allowing of training the gun on any ordinary bearing in English built ships. The English (for a very long time it was English only)41 realisation of the possibilities of the porthole in Henry VIII’s reign contributed very materially to the defeat of the Spanish Armada some decades later. Indeed, it is no exaggeration to say that the porthole was to that era what the torpedo has been in the present one. Introduced about 1875 as a trivial alternative to the gun, in less than forty years the torpedo came to challenge the gun in range to an extent that as early as 1905 or thereabouts began profoundly to affect all previous ideas of naval tactics, and that by 1915 has changed them altogether!

Another great change of these Henry VIII days was in the form of the ships.6 At this era they began to be built with “tumble-home” sides, instead of sides slanting outwards upwards, and inwards downwards as heretofore. With the coming of the porthole came the decline of the cross-bow as a naval arm. In the pre-porthole days every record speaks of “showers of arrows,” and the gun appears to have been a species of accessory. In the early years of the Sixteenth Century it became the main armament, and so remained unchallenged till the present century and the coming of the long-range torpedo.

Henry VIII’s reign is also remarkable for the first institution of those “cutting out” expeditions which were afterwards to become such a particular feature of British methods of warfare. This first attempt happened in the year 1513, when Sir Edward Howard, finding the French fleet lying in Brest Harbour refusing to come out, “collected boats and barges” and attacked them with those craft. The attempt was42 not successful, but it profoundly affected subsequent naval history.

Therefrom the French were impressed with the idea that if a fleet lay in a harbour awaiting attack it acquired an advantage thereby. The idea became rooted in the French mind that to make the enemy attack under the most disadvantageous circumstances was the most wise of policies. That “the defensive is compelled to await attack, compelled to allow the enemy choice of the moment” was overlooked!

From this time onward England was gradually trained by France into the role of the attacker, and the French more and more sank into the defensive attitude. Many an English life was sacrificed between the “discovery of the attack” in the days of Henry VIII, and its triumphant apotheosis when centuries later Nelson won the Battle of the Nile; but the instincts born in Henry’s reign, on the one hand to fight with any advantage that the defensive might offer, on the other hand to attack regardless of these advantages, are probably the real key to the secret of later victories.

The Royal ships at this period were manned by voluntary enlistment, supplemented by the press-gang as vacancies might dictate. The pay of the mariner was five shillings a month; but petty officers, gunners and the like received additional pickings out of what was known as “dead pay.” By this system the names of dead men, or occasionally purely fancy names, were on the ship’s books, and the money drawn for these was distributed in a fixed ratio. The most interesting feature of Henry VII and Henry VIII’s navies is the presence in them of a number of Spaniards, who presumably43 acted as instructors. These received normal pay of seven shillings a month plus “dead pay.”

The messing of the crews was by no means indifferent. It was as follows per man:—

Sunday, Tuesday, Thursday: ¾ lb. beef and ½ lb. bacon.

Monday, Wednesday, Saturday: Four herrings and two pounds of cheese.

Friday: To every mess of four men, half a cod, ten herrings, one pound of butter and one pound of cheese.

There was also a daily allowance of one pound of bread or biscuit. The liquid allowance was either beer, or a species of grog consisting of one part of sack to two of water. Taking into account the value of money in those days and the scale of living on shore at the time, the conditions of naval life were by no means bad, though complaints of the low pay were plentiful enough. Probably, few received the full measure of what on paper they were entitled to.

Henry VIII died early in 1547. In the subsequent reigns of Edward VI and Mary, the Navy declined, and little use was made of it except for some raiding expeditions.

When Elizabeth came to the throne the regular fleet had dwindled to very small proportions, and, war being in progress, general permission was given for privateering as the only means of injuring the enemy. It presently degenerated into piracy and finally had to be put down by the Royal ships.

No sooner, however, was the war over than the Queen ordered a special survey to be made of the Navy. New ships were laid down and arsenals established for44 the supply of guns and gunpowder, which up to that time had been imported from Germany. Full advantage was taken of the privateering spirit, the erstwhile pirates being encouraged to undertake distant voyages. In many of these enterprises the Queen herself had a personal financial interest. She thus freed the country from various turbulent spirits who were inconvenient at home, and at one and the same time increased her own resources by doing so.

There is every reason to believe that this action of Elizabeth’s was part of a well-designed and carefully thought out policy. The type of ship suitable for distant voyages and enterprises was naturally bound to become superior to that which was merely evolved from home service. The type of seamen thus bred was also necessarily bound to be better than the home-made article. Elizabeth can hardly have failed to realise these points also.

To the personnel of the regular Navy considerable attention was also given. Pay was raised to 6/8 per month for the seamen, and 5/- a month with 4/- a month for clothing for soldiers afloat. Messing was also increased to a daily ration of one pound of biscuit, a gallon of beer, with two pounds of beef per man four days out of the seven, and a proportionate amount of fish on the other three days. Subsequently, and just previous to the Armada, the pay of seamen rose to 10/- a month, with a view to inducing the better men not to desert.

The regular navy was thus by no means badly provided for as things went in those days; while service with “gentlemen adventurers” offered attractions to a very considerable potential reserve, and so England contained a large population which, from one cause45 and another, was available for sea service. To these circumstances was it due that the Spanish Armada, when it came, never had the remotest possibility of success. It was doomed to destruction the day that Elizabeth first gave favour to the “gentlemen adventurers.”

Of these adventurers the greatest of all was Francis Drake, who in 1577 made his first long voyage with five ships to the Pacific Ocean. Drake, alone, in the Pelican, succeeded in reaching the Pacific and carrying out his scheme of operations, which—not to put too fine a point on it—consisted of acts of piracy pure and simple against the Spaniards. He returned to England after an absence of nearly three years, during which he circumnavigated the globe.

There is little doubt that Drake in this voyage, and others like him in similar expeditions, learned a great deal about the disadvantages of small size in ships. Drake, however, learned another thing also. Up to this day the crew of a ship had consisted of the captain and a certain military element; also the master, who was responsible for a certain number of “mariners.” The former were concerned entirely with fighting the ship—the latter entirely with manœuvring it.

This system of specialisation, awkward as it appears thus baldly stated, may have worked well enough in ordinary practice. It did not differ materially from the differentiation between deck hands and the engineering departments, which to a greater or less extent is very marked in every navy of the present day.

Drake, however, started out with none too many men, and it was not long before he lost some of those he had and found himself short-handed. His solution of46 the difficulty is in his famous phrase, “I would have the gentlemen haul with the mariners.” How far this was a matter of expediency, how far the revelation of a new policy, is a matter of opinion. It must certainly have been outside the purview of Elizabeth. But out of it gradually came that every English sailor knew how to fight his ship and how to sail her too, and this amounted to doubling the efficiency of the crew of any ship at one stroke.

Of Drake himself, the following contemporary pen-picture, from a letter written by one of his Spanish victims, Don Franciso de Zarate,7 explains almost everything:—

“He received me favourably, and took me to his room, where he made me seated and said to me: ‘I am a friend to those who speak the truth, that is what will have the most weight with me. What silver or gold does this ship bring?’

“... We spoke together a great while, until the dinner-hour. He told me to sit beside him and treated me from his dishes, bidding me have no fear, for my life and goods were safe; for which I kissed his hands.

“This English General is a cousin of John Hawkins; he is the same who, about five years ago, took the port of Nombre de Dios; he is called Francis Drake; a man of some five and thirty years, small of stature and red-bearded, one of the greatest sailors on the sea, both from skill and power of commanding. His ship carried about 400 tons, is swift of sail, and of a hundred men, all skilled and in their prime, and all as much experienced in warfare as if they were old soldiers of Italy. Each one, in particular, takes great pains to keep his arms clean;8 he treats them with affection, and they treat him with respect. I endeavoured to find out whether the General was liked, and everyone told me he was adored.”

Less favourable pictures of Drake have been penned, and there is no doubt that some of his virtues have been greatly exaggerated. At the present day there is perhaps too great a tendency to reverse the process.47 Stripped of romance, many of his actions were petty, while those of some of his fellow adventurers merit a harsher name. Hawkins, for instance, was hand-in-glove with Spanish smugglers and a slave trader. Many of the victories of the Elizabethan “Sea-Kings” were really trifling little affairs, magnified into an importance which they never possessed.

But, when all is said and done, it is in these men that we find the birth of a sea spirit which still lingers on, despite that other insular spirit previously referred to—the natural tendency of islanders to regard the water itself as a bulwark, instead of the medium on which to meet and defeat the enemy.

The Spanish, already considerably incensed by the piratical acts of the English “gentlemen adventurers,” presently found a further cause of grievance in the assistance rendered by Elizabeth to their revolting provinces in the Netherlands. Drake had not returned many years from his famous voyage when it became abundantly clear that the Spaniards no longer intended quietly to suffer from English interference.

Spain at that time was regarded as the premier naval power of Europe. Her superiority was more mythical than actual, for reasons which will later on be referred to: however, her commercial oversea activities were very great. The wealth which she wrung from the Indies—though probably infinitely less than its supposed value—was sufficient to enable her to equip considerable naval forces, certainly larger ones numerically than any which England alone was able to bring against them.

48

Knowledge of the fact that Spain was preparing the Armada for an attack on England, led to the sailing of Drake in April, 1587, with a fleet consisting of four large and twenty-six smaller ships, for the hire of which the citizens of London were nominally or actually responsible. His real instructions are not known, but there is little question that, as in all similar expeditions, he started out knowing that his success would be approved of, although in the event of any ill-success or awkward questions, he would be publicly disavowed.

Reaching Cadiz, he destroyed 100 store ships which he found there; and then proceeding to the Tagus, offered battle to the Spanish war fleet. The Spanish admiral, however, declined to come out—a fact which of itself altogether discredits the popular idea about the vast all-powerful ships of Spain, and the little English ships, which, in the Armada days, could have done nothing against them but for a convenient tempest. On account of this expedition of Drake’s, the sailing of the Armada was put off for a year. So far as stopping the enterprise was concerned, Drake’s expedition was a failure. Armada preparations still went on.

It is by no means to be supposed that the Armada in its conception was the foolhardy enterprise that on the face of things it looks to have been. The idea of it was first mooted by the Duke of Alva so long ago as 1569. In 1583 it became a settled project in the able hands of the Marquis of Santa Cruz, who alone among the Spaniards was not more or less afraid of the English. In the battle of Tercera in 1583, certain ships, which if not English were at any rate supposed to be, had shown the white feather. Santa Cruz assumed therefrom that the English were easily to be overwhelmed49 by a sufficiently superior force, and he designed a scheme whereby he would use 556 ships and an army of 94,222 men.

Philip of Spain had other ideas. Having a large army under the Duke of Parma in the Netherlands, he proposed that this force should be transported thence to England in flat-bottomed boats, while Santa Cruz should take with him merely enough ships to hold the Channel, and prevent any interference by the English ships with the invasion.

Before the delayed Armada could sail Santa Cruz died; and despite his own protestations Medina Sidonia was appointed in Santa Cruz’s place to carry out an expedition in which he had little faith or confidence. His total force at the outset consisted of 130 ships and 30,493 men. Of these ships not more than sixty-two at the outside were warships, and some of these did not carry more than half-a-dozen guns.

The main English fighting force consisted of forty-nine warships, some of which were little inferior to the Spanish in tonnage, though all were much smaller to the eye, as they were built with a lower freeboard and without the vast superstructures with which the Spaniards were encumbered. As auxiliaries, the English had a very considerable force of small ships; also the Dutch fleet in alliance with them.

The guns of the English ships were, generally speaking, heavier, all their gunners were well trained, and their portholes especially designed to give a considerable arc of fire, whereas the Spanish had very indifferent gunners and narrow portholes. The Spaniards themselves thoroughly recognised their inferiority in the matter of gunnery, and the specific instructions50 of their admiral were that he was to negative this inferiority by engaging at close quarters, and trust to destroying the enemy by small-arm fire from his lofty superstructures.

The small portholes of the Spanish ships, which permitted neither of training, nor elevation, nor depression, are not altogether to be put down to stupidity or neglect of progress, for all that they were mainly the result of ultra-conservatism. The gun—as Professor Laughton has made clear—was regarded in Spain as a somewhat dishonourable weapon. Ideals of “cold steel” held the field. Portholes were kept very small, so that enemies relying on musketry should not be able to get the advantage that large portholes might supply. To close with the enemy and carry by boarding was the be-all and end-all of Spanish ideas of naval warfare. When able to employ their own tactics they were formidable opponents, though to the English tactics merely so many helpless haystacks.

On shore, in England, the coming of the Armada provoked a good deal of panic; though the army which Elizabeth raised and reviewed at Tilbury was probably got together more with a view to allaying this panic than from any expectations that it would be actually required. The views of the British seamen on the matter were entirely summed up in Drake’s famous jest on Plymouth Hoe, that there was plenty of time to finish the game of bowls and settle the Spaniards afterwards!

Yet this very confidence might have led to the undoing of the English. The researches of Professor Laughton have made it abundantly clear that had53 Medina Sidonia followed the majority opinion of a council of war held off the Lizard, he could and would have attacked the English fleet in Plymouth Sound with every prospect of destroying it, because there, and there only, did opportunity offer them that prospect of a close action upon which their sole chance of success depended. Admiral Colomb has elaborated the point still further, with a quotation from Monson to the effect that had the Armada had a pilot able to recognise the Lizard, which the Spaniards mistook for Ramehead, they might have surprised the English fleet at Plymouth. This incident covers the whole of what Providence or luck really did for England against the Spanish.

To a certain extent a parallel of our own day exists. When Rodjestvensky with the Baltic fleet reached Far Eastern waters, there came a day when his cruisers discovered the entire Japanese fleet lying in Formosan waters. The Russian admiral ignored them and went on towards Vladivostok. The parallel ends here because the “Japanese fleet” was merely a collection of dummies intended to mislead him.9

The first engagement with the Spanish Armada took place on Sunday, June 21st. It was more in the nature of a skirmish than anything else. The Spaniards made several vain and entirely ineffectual attempts to close with the swifter and handier English vessels. They took care, however, to preserve their formation,54 and so to that extent defeated the English tactics, which were to destroy in detail what could not be destroyed without heavy loss in the mass. So the Spaniards reached Calais on the 27th with a loss of only three large ships.

They there discovered that Parma’s flat-bottomed boats were all blockaded by the Dutch, and that any invasion of England was therefore entirely out of the question. It must have been perfectly obvious to the most sanguine of them by this that they could not force action with the swifter English ships, while they could not relieve the blockaded boats without being attacked at the outset. In a word, the Armada was an obvious failure.

On the night of the 28th, fire ships were sent into the Spanish fleet by the English. This, though the damage done was small, brought the Spanish to sea, and the next morning they were attacked off Gravelines by the English. The battle was hardly of the nature of a fleet action, so much as well-designed tactical operations intended to keep the enemy on the move. It resulted in the Spaniards losing only seven ships in a whole day’s fighting. The only really serious loss that the Spaniards sustained was that they were driven into the North Sea, with no prospect of returning home except by way of the North of Scotland.