| FRED BARNARD | GORDON THOMSON |

| HABLOT K. BROWNE (Phiz) | J. McL. RALSTON |

| J. MAHONEY | H. FRENCH |

| CHARLES GREEN | E. G. DALZIEL |

| A. B. FROST | F. A. FRASER |

| and SIR LUKE FILDES | |

| Title Design | By Gordon Thomson | |||

| Sketches by Boz | 34 | Illustrations | by | Fred Barnard |

| The Pickwick Papers | 57 | " | " | Phiz |

| Oliver Twist | 28 | " | " | J. Mahoney |

| Nicholas Nickleby | 59 | " | " | Fred Barnard |

| Master Humphrey's Clock and other Stories | 9 | " | " | Fred Barnard |

| The Old Curiosity Shop | 39 | " | " | Charles Green |

| Barnaby Rudge | 46 | " | " | Fred Barnard |

| American Notes | 10 | " | " | A. B. Frost |

| Martin Chuzzlewit | 59 | " | " | Fred Barnard |

| Christmas Books | 28 | " | " | Fred Barnard |

| Pictures from Italy | 8 | " | " | Gordon Thomson |

| Dombey and Son | 62 | " | " | Fred Barnard |

| David Copperfield | 61 | " | " | Fred Barnard |

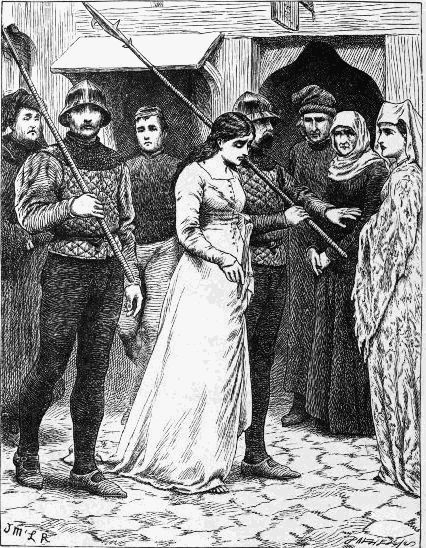

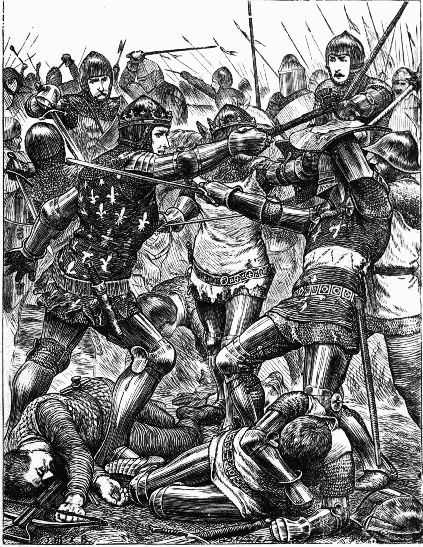

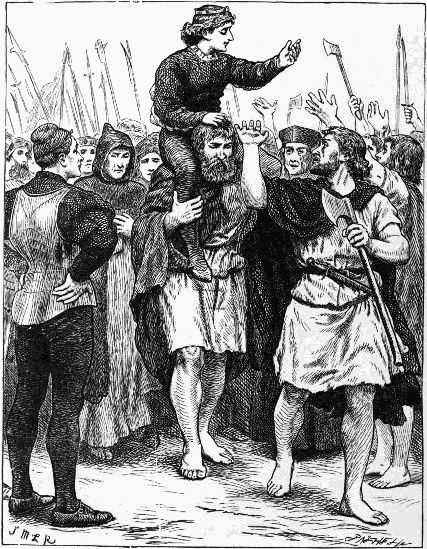

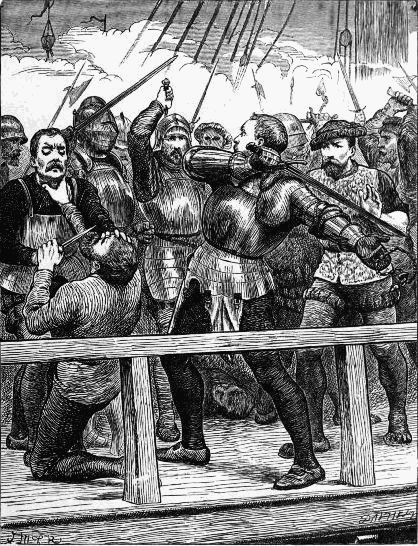

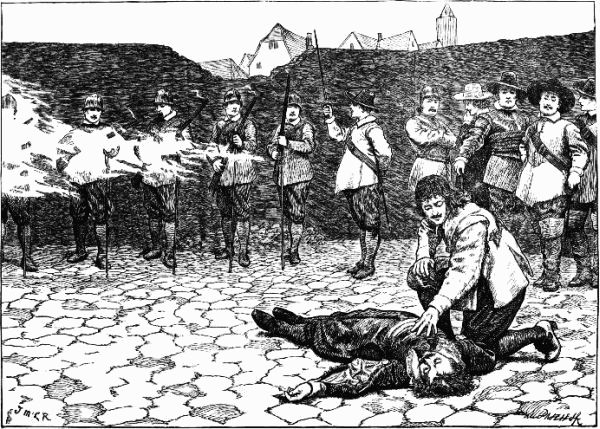

| A Child's History of England | 15 | " | " | J. McL. Ralston |

| Bleak House | 61 | " | " | Fred Barnard |

| Hard Times | 20 | " | " | H. French |

| Little Dorrit | 58 | " | " | J. Mahoney |

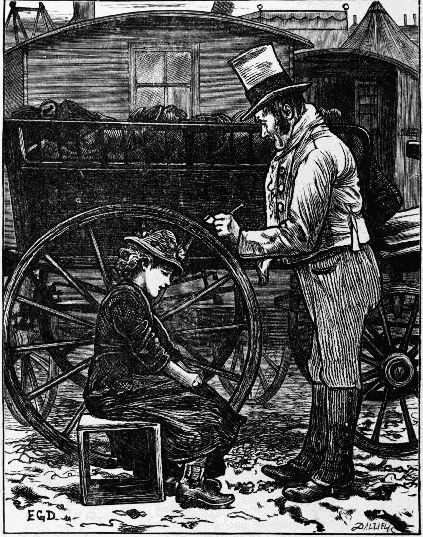

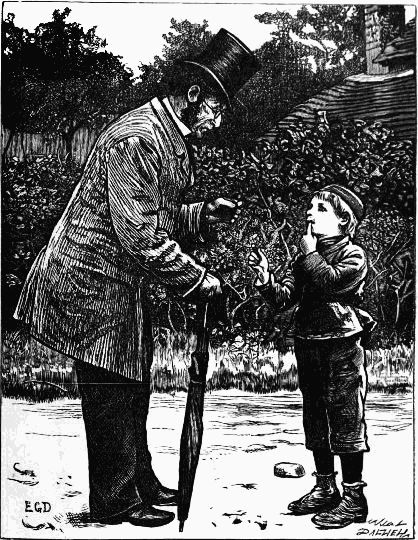

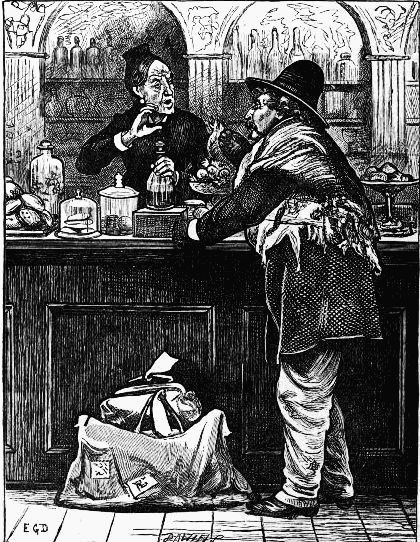

| Reprinted Pieces | 9 | " | " | E. G. Dalziel |

| A Tale of Two Cities | 25 | " | " | Fred Barnard |

| Uncommercial Traveller | 26 | " | " | E. G. Dalziel |

| Great Expectations | 30 | " | " | F. A. Frazer |

| Our Mutual Friend | 58 | " | " | J. Mahoney |

| Christmas Stories | 23 | " | " | E. G. Dalziel |

| Edwin Drood | 12 | " | " | Luke Fildes |

| Life of Dickens | 28 | " | " | Fred Barnard |

It happens, however, that there does exist a series of Dickens illustrations, now in some danger of being unduly neglected, in which the artists were wonderfully happy in preserving[x] the original features of Phiz and Cruikshank's interpretations, while they toned down the more extravagant details and brought imagination into closer harmony with reality. These were the illustrations to the square-shaped "Household Edition," published in 1870, just after the great novelist's death—and now reissued in this Dickens picture-book, in the hope that those who love the stories may like to possess in separate form what is, perhaps, the best pictorial accompaniment that the novels ever received. At the time of its first publication, the "Household Edition" enjoyed an enormous success. At the moment the name of Dickens was on every one's lips, and the fact that this splendidly illustrated reprint was issued in penny numbers and sixpenny parts placed it within reach of even the most humbly stocked purse. Its sale was stupendous, and the familiar green-covered pamphlets percolated through every town and village where the English tongue is spoken. The original copies may still be met with, under many a country timbered roof, carefully treasured as one of the most cherished household possessions.

Undoubtedly, a great part of the success was due to the art of the illustrators. To begin with, there was an unusually liberal display of pictures—the edition, as a whole, containing close upon nine hundred. But more important than the number were the truth and sincerity of the interpretations—qualities which helped to give a new life to characters already secure of immortality. First and foremost, of course, the edition will always be associated with the memory of Fred Barnard, whose pictures are the outstanding feature of the present volume. Barnard seemed destined by nature to illustrate Dickens; the spirit of "Boz" ran again in his veins. And nothing in his work is more impressively ingenious than the skill with which he took the types already created by his predecessors, preserved[xi] their characteristics, so that each was unmistakably himself, and yet by the illuminating touch of genius transferred them every one from the realm of caricature to that of portraiture. Not far inferior to him was that admirable draughtsman, Charles Green, who exactly adopted Barnard's attitude to the originals. The reader who will compare Green's illustrations to "The Old Curiosity Shop" with Phiz's, will scarcely fail to notice with interest how often Green has chosen the same subject as his predecessor, and all but treated it in the same manner, save that a twisted grotesque suddenly becomes, under the magic of his wand, a natural human being. His picture of Sally Brass and the Marchioness is a remarkable instance in point: but there are many others equally eloquent of his sympathetic and interpretative method. Nor should the work of Mahony, A. B. Frost, Gordon Thomson and others be forgotten, for each in his own way has helped to make this volume, what its publishers confidently claim it to be, a collection of Dickens pictures unrivalled for humour, pathos, character, and interpretative skill. In the certainty that such a gallery of good work can hardly fail to find appreciators, the volume is now offered to all lovers of the most widely popular author of the Victorian Era.

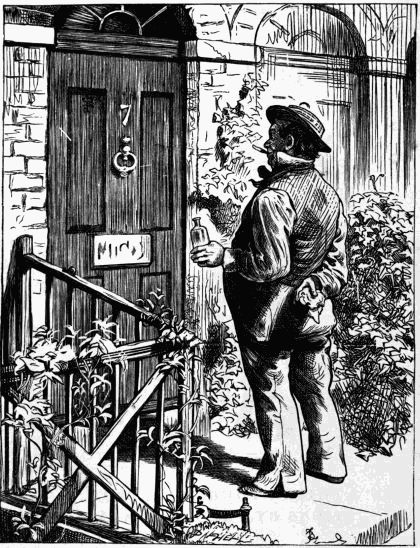

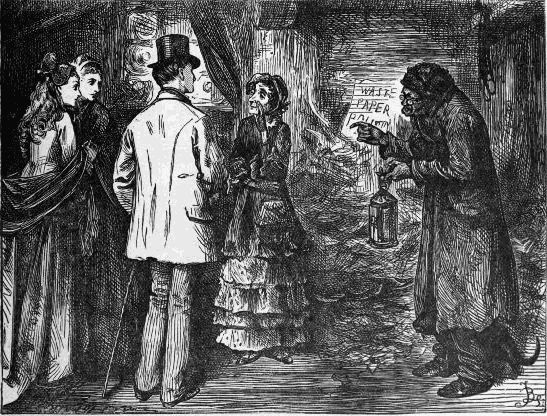

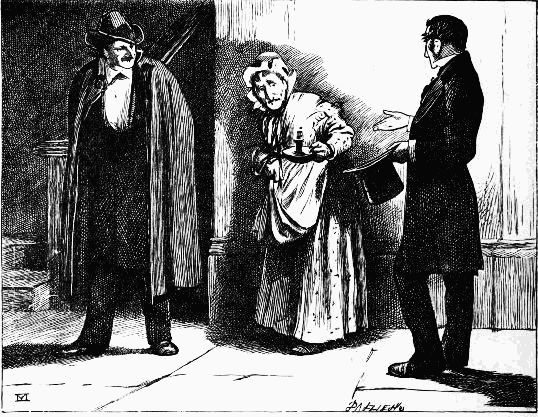

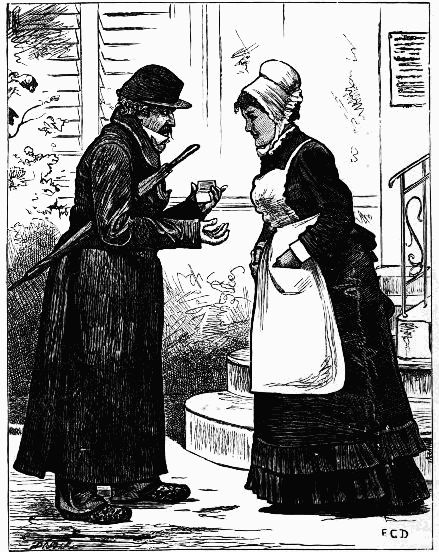

The Half-pay Captain completely effaced the old lady's name from the

brass door-plate in his attempts to polish it with aqua-fortis—Our Parish, chap. ii.

The Half-pay Captain completely effaced the old lady's name from the

brass door-plate in his attempts to polish it with aqua-fortis—Our Parish, chap. ii.

When he first came to look at the lodgings, he inquired most particularly whether he was

sure to be able to get a seat in the Parish Church—Our Parish, chap. vii.

When he first came to look at the lodgings, he inquired most particularly whether he was

sure to be able to get a seat in the Parish Church—Our Parish, chap. vii.

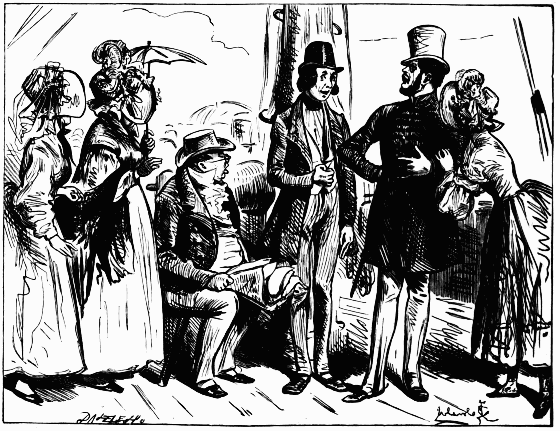

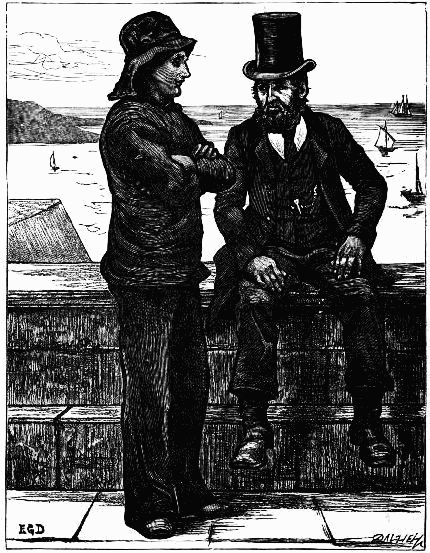

The Gravesend boat.—Scenes, chap. x.

The Gravesend boat.—Scenes, chap. x.

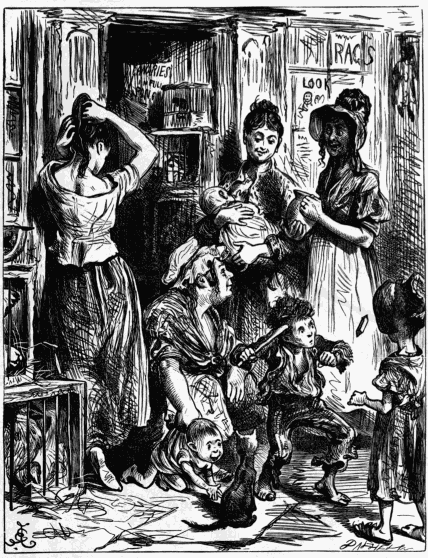

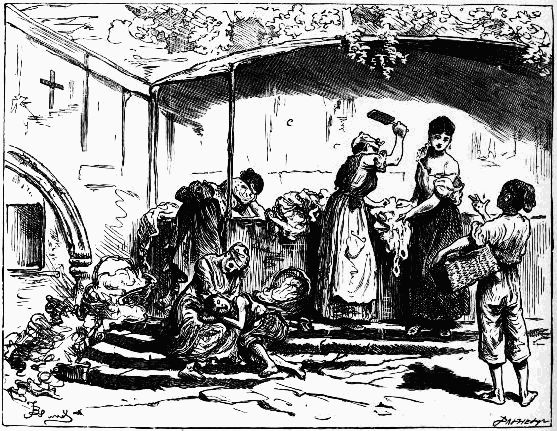

Different women of the House gossiping on the steps . . . the native

Diallers—Scenes, chap. v.

Different women of the House gossiping on the steps . . . the native

Diallers—Scenes, chap. v.

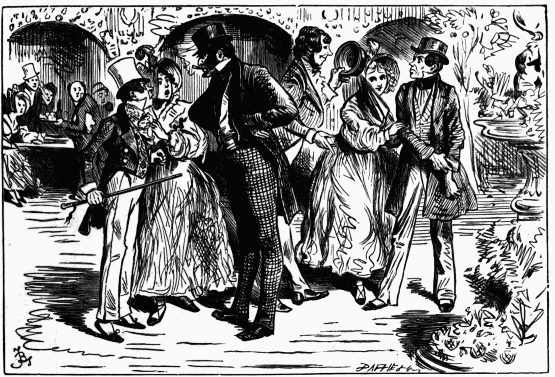

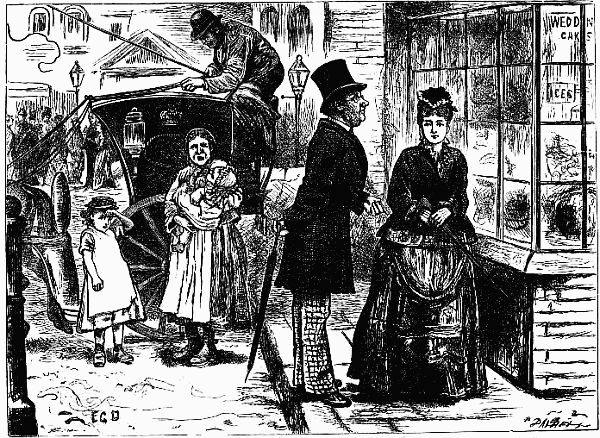

It was a wedding party and sketched from one of the interior streets near Fitzroy Square—Scenes, chap. vii.

It was a wedding party and sketched from one of the interior streets near Fitzroy Square—Scenes, chap. vii.

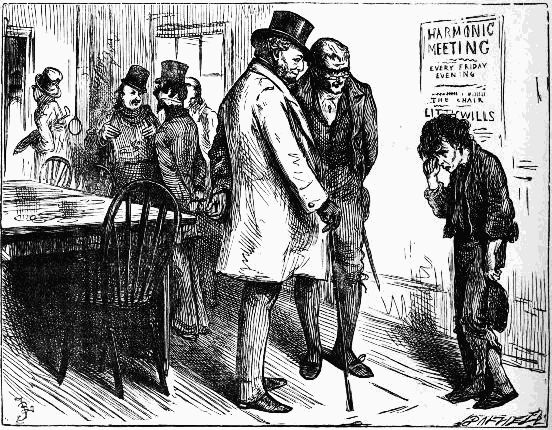

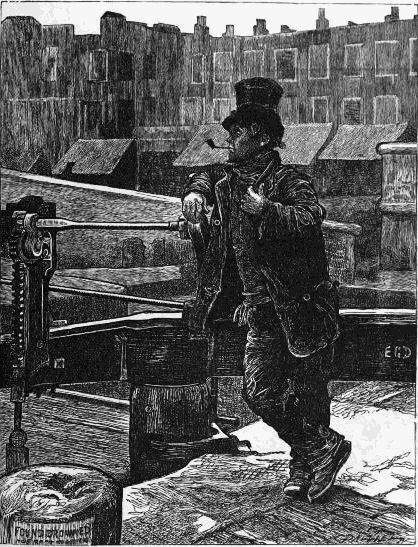

"I may as well get board, lodgin', and washin' till then, out of the country, as pay for it

myself; consequently here goes"—Scenes, chap. xvii.

"I may as well get board, lodgin', and washin' till then, out of the country, as pay for it

myself; consequently here goes"—Scenes, chap. xvii.

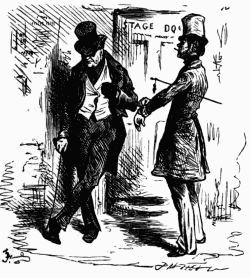

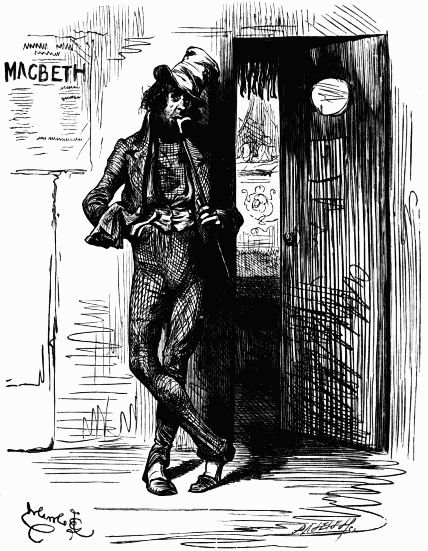

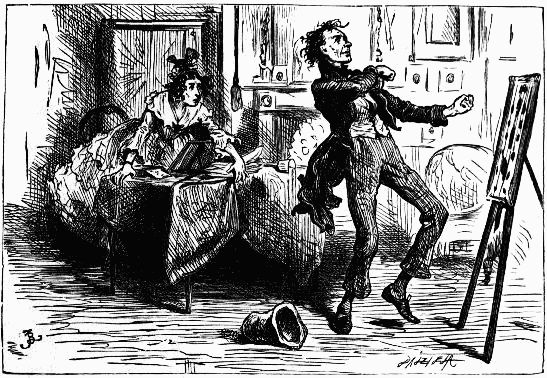

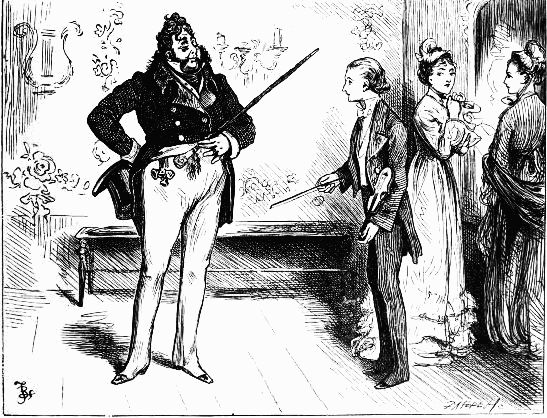

"His line is genteel comedy—his father's coal and potato. He does

Alfred Highflier in the last piece, and very well he'll do it—at the

price."—Scenes, chap. xiv.

"His line is genteel comedy—his father's coal and potato. He does

Alfred Highflier in the last piece, and very well he'll do it—at the

price."—Scenes, chap. xiv.

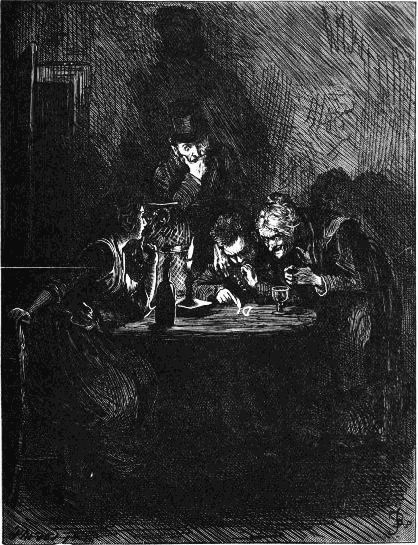

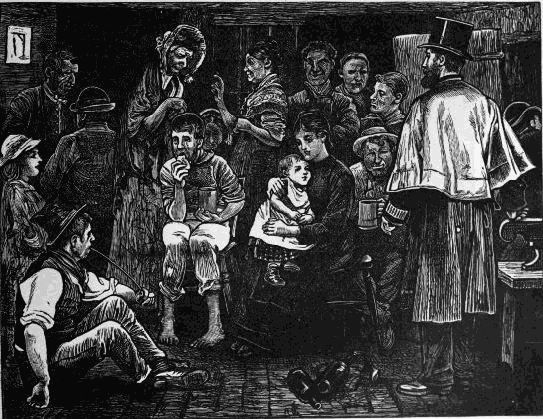

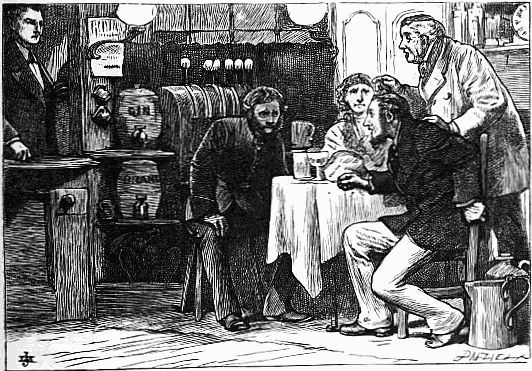

A gin-shop—Scenes, chap. xxii.

A gin-shop—Scenes, chap. xxii.

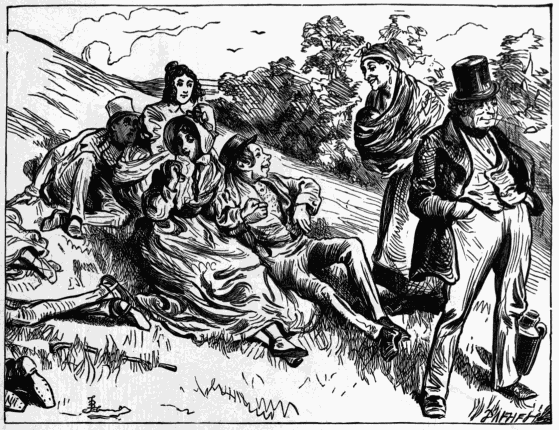

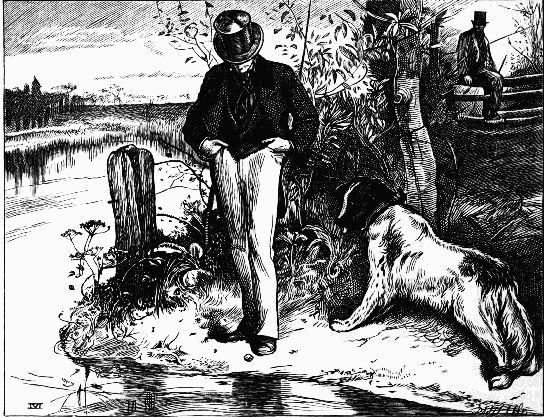

Children were playing on the grass; groups . . . chatting and laughing; but the man walked

steadily up and down, unheeding and unheeded—Characters, chap. i.

Children were playing on the grass; groups . . . chatting and laughing; but the man walked

steadily up and down, unheeding and unheeded—Characters, chap. i.

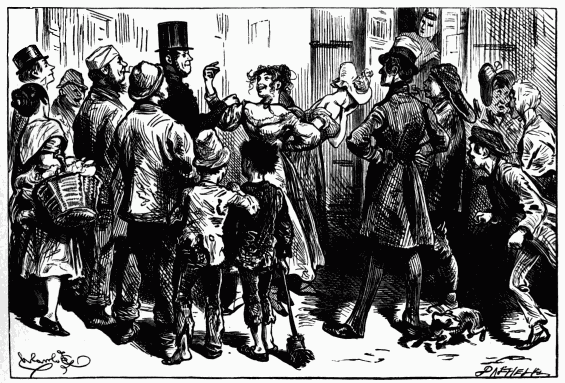

The Prisoners' van—Characters, chap. xii.

The Prisoners' van—Characters, chap. xii.

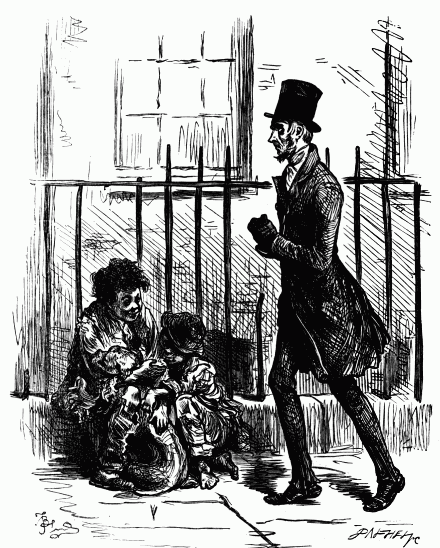

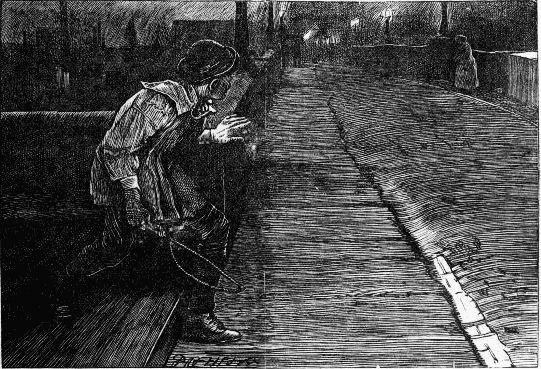

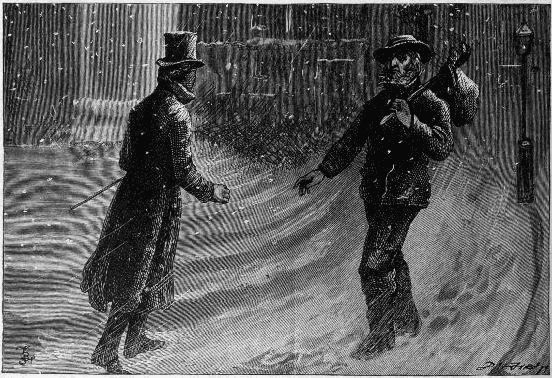

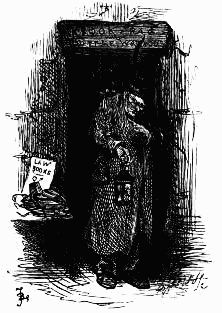

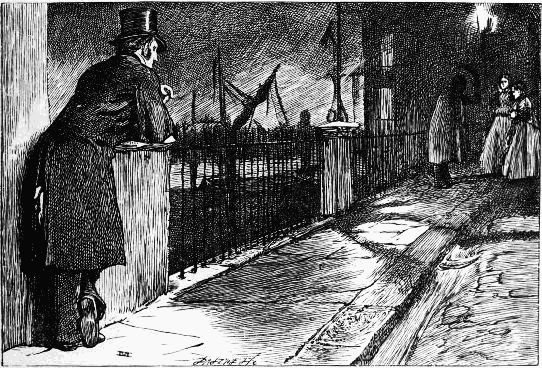

Hurrying along a by-street, keeping as close as he can to the area

railings, a Man of about forty or fifty, clad in an old rusty

suit of threadbare black cloth—Characters, chap. x.

Hurrying along a by-street, keeping as close as he can to the area

railings, a Man of about forty or fifty, clad in an old rusty

suit of threadbare black cloth—Characters, chap. x.

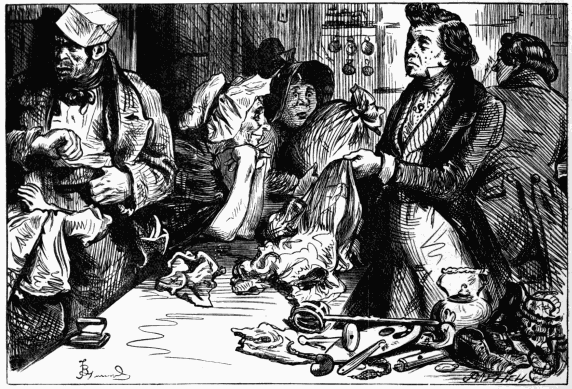

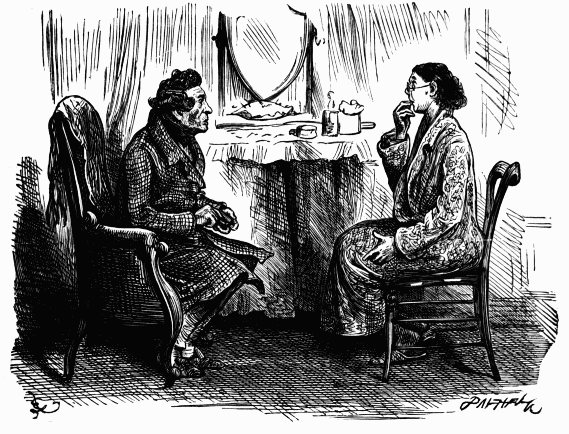

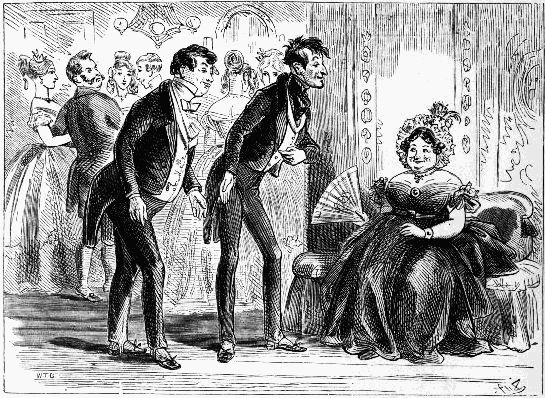

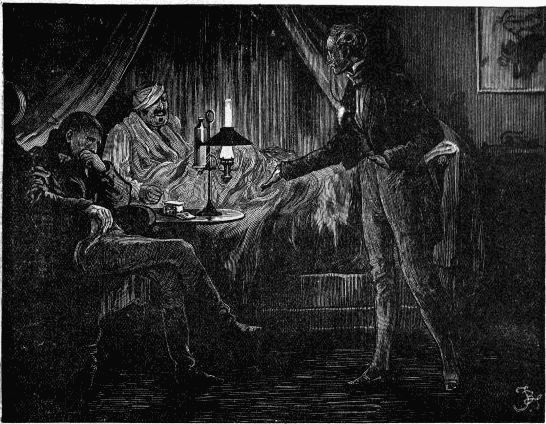

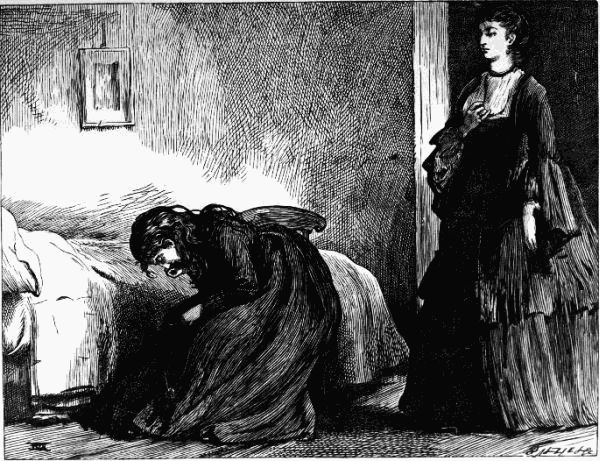

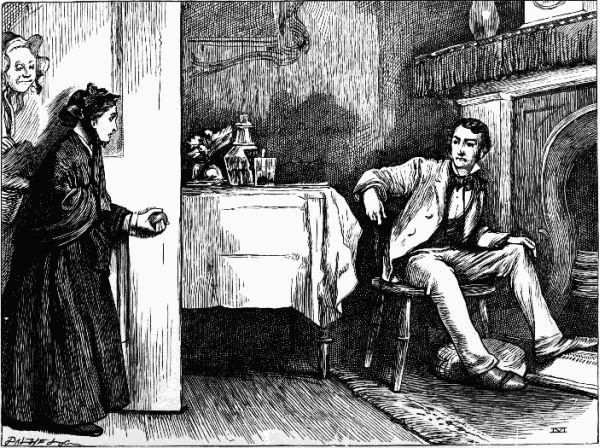

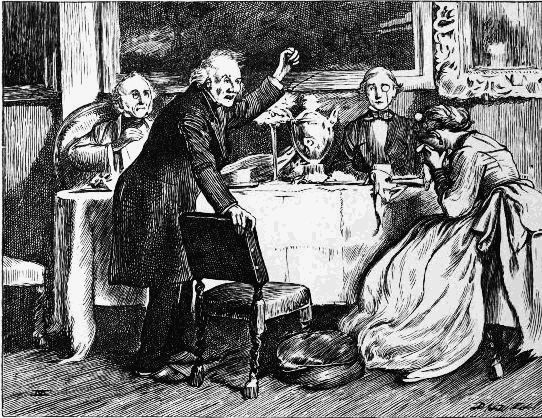

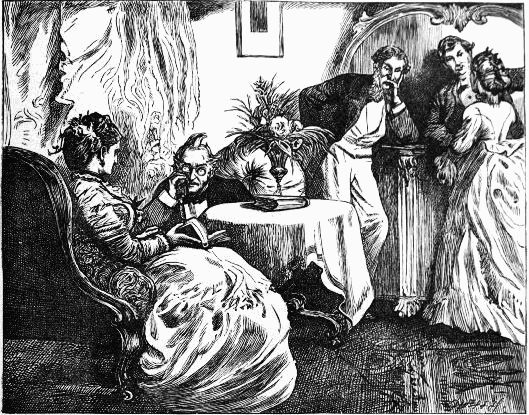

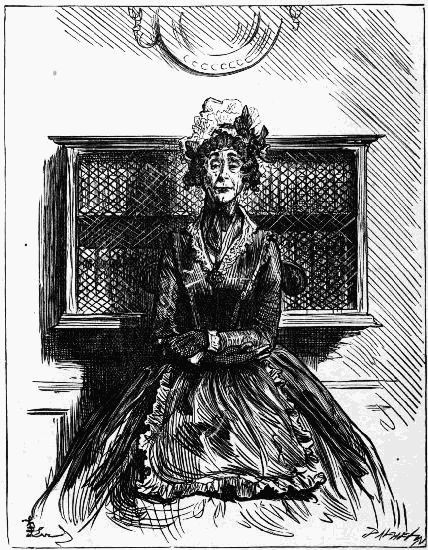

"No what?" inquired Mrs. Bloss with a look of the most indescribable alarm

"No stomach," repeated Mrs. Tibbs with a shake of the head—Tales, chap. i.

"No what?" inquired Mrs. Bloss with a look of the most indescribable alarm

"No stomach," repeated Mrs. Tibbs with a shake of the head—Tales, chap. i.

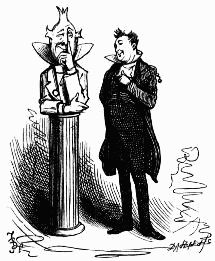

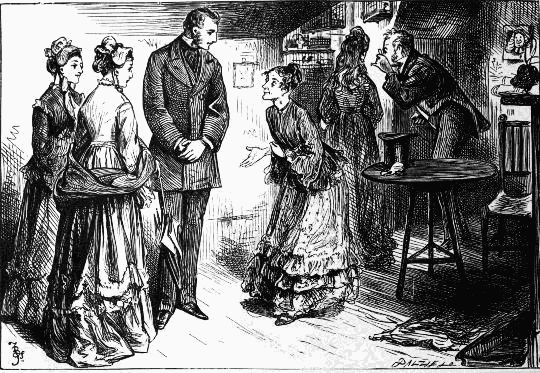

"So exactly the air of the Marquis," said the Military Gentleman—Tales, chap. iv.

"So exactly the air of the Marquis," said the Military Gentleman—Tales, chap. iv.

"How delightful, how refreshing it is, to retire from the cloudy storms,

the vicissitudes, and the troubles of life, even if it be but for a few

fleeting moments."—Tales, chap. v.

"How delightful, how refreshing it is, to retire from the cloudy storms,

the vicissitudes, and the troubles of life, even if it be but for a few

fleeting moments."—Tales, chap. v.

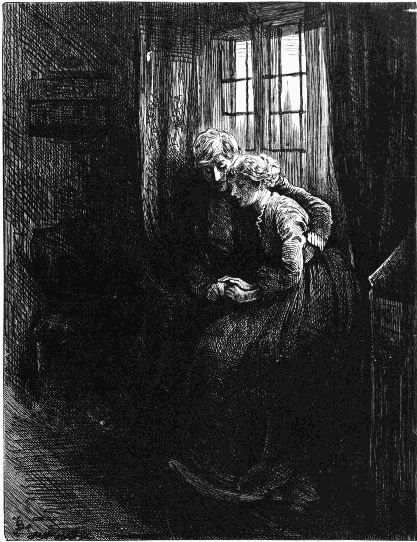

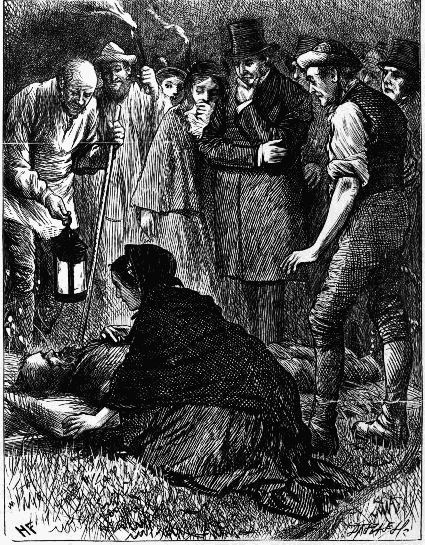

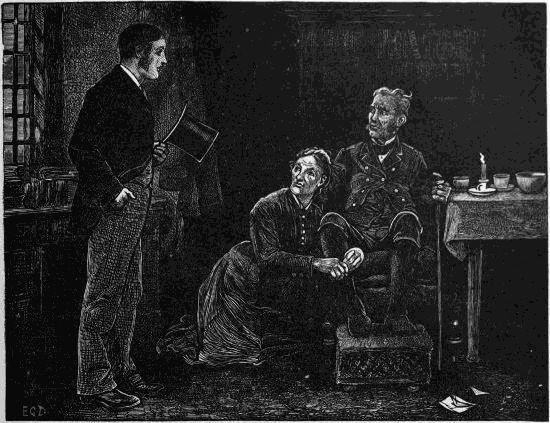

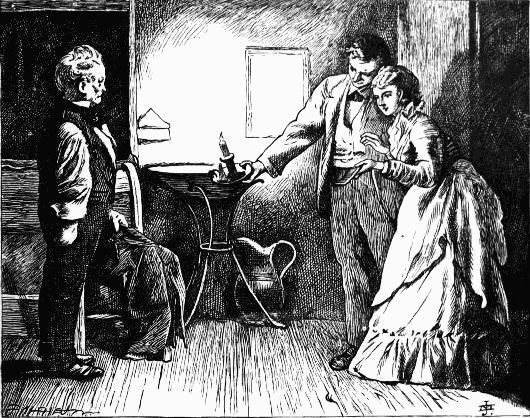

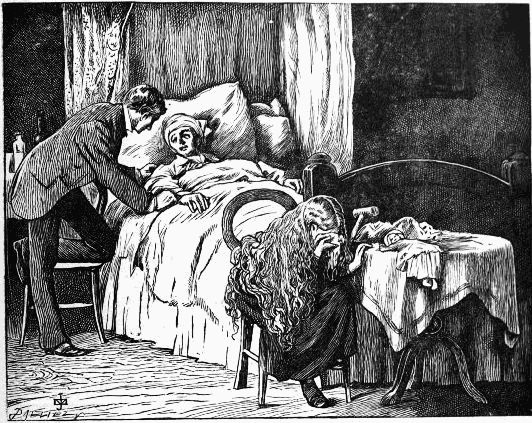

"Who was he?" inquired the Surgeon. "My Son!" rejoined the Woman; and fell senseless at his feet—Tales, chap. vi.

"Who was he?" inquired the Surgeon. "My Son!" rejoined the Woman; and fell senseless at his feet—Tales, chap. vi.

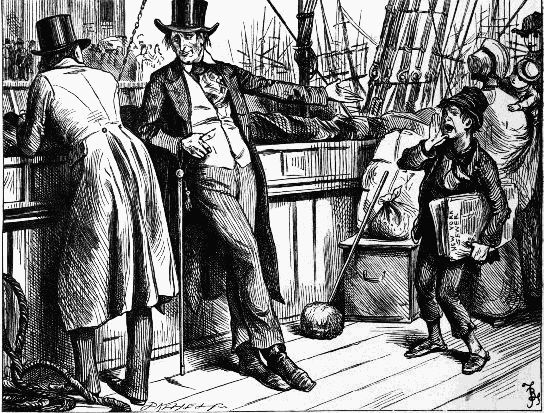

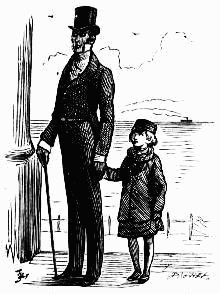

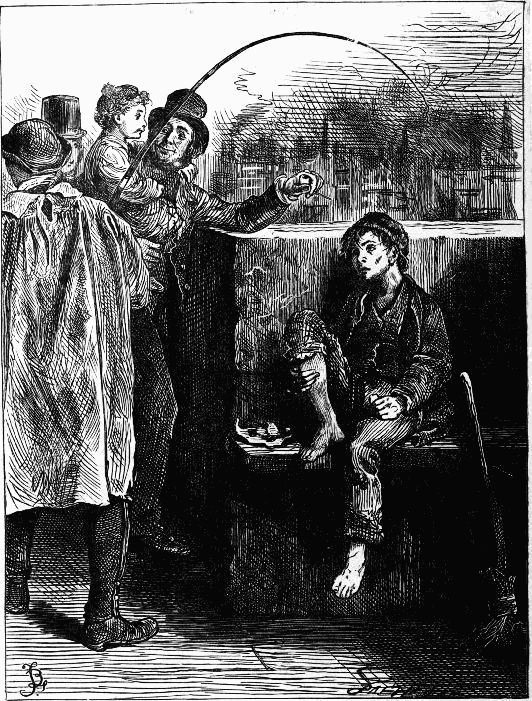

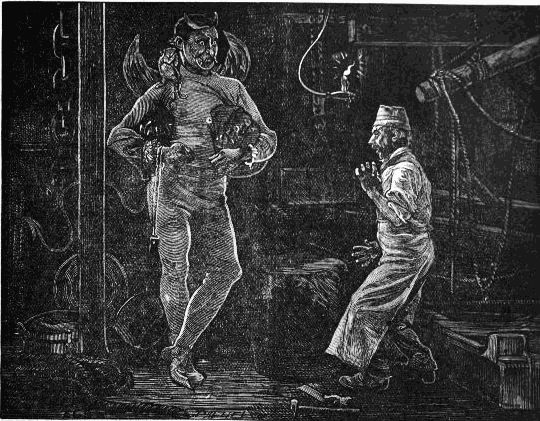

The facetious Hardy, in fulfilment of his promise, had watched the Child to

a remote part of the vessel, and, suddenly appearing before him with the

most awful contortions of visage, had produced his paroxysms of terror—Tales,

chap. vii.

The facetious Hardy, in fulfilment of his promise, had watched the Child to

a remote part of the vessel, and, suddenly appearing before him with the

most awful contortions of visage, had produced his paroxysms of terror—Tales,

chap. vii.

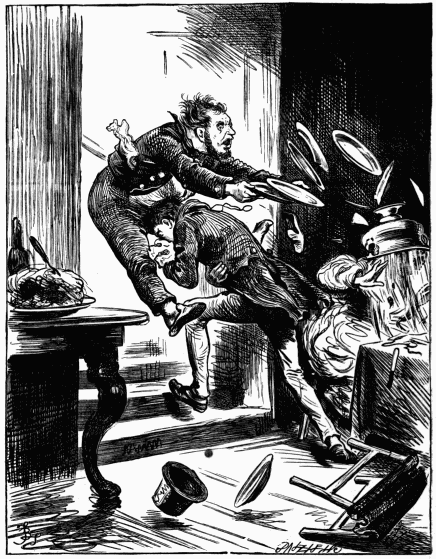

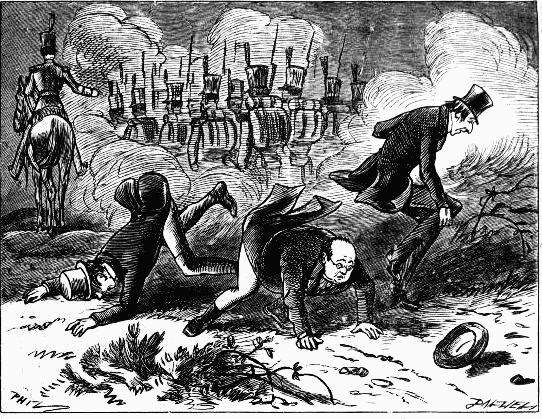

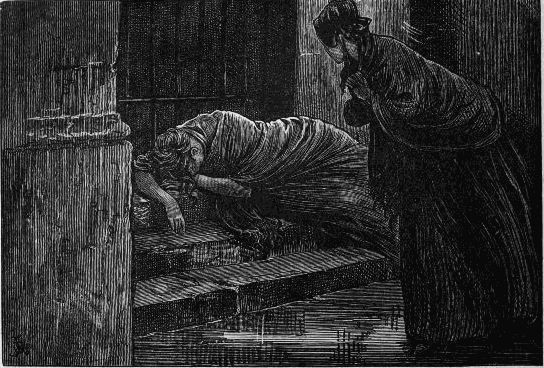

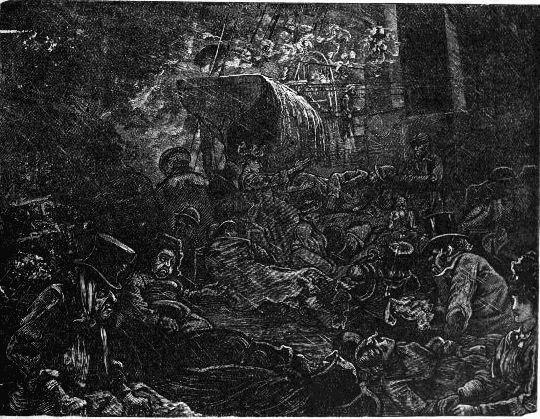

One Gentleman was observed suddenly to rush from table without the slightest

ostensible reason, and dart up the steps with incredible swiftness, thereby

greatly damaging both himself and the Steward, who happened to be coming

down at the same moment—Tales, chap. vii.

One Gentleman was observed suddenly to rush from table without the slightest

ostensible reason, and dart up the steps with incredible swiftness, thereby

greatly damaging both himself and the Steward, who happened to be coming

down at the same moment—Tales, chap. vii.

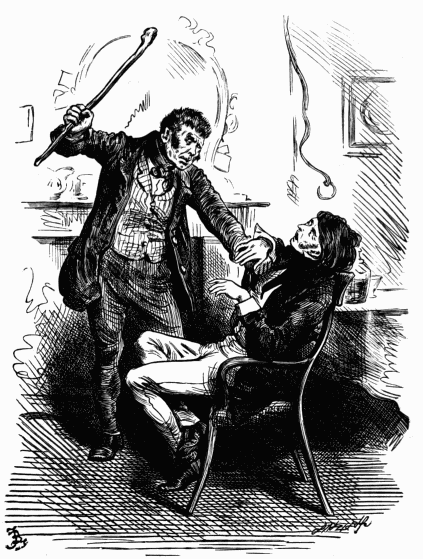

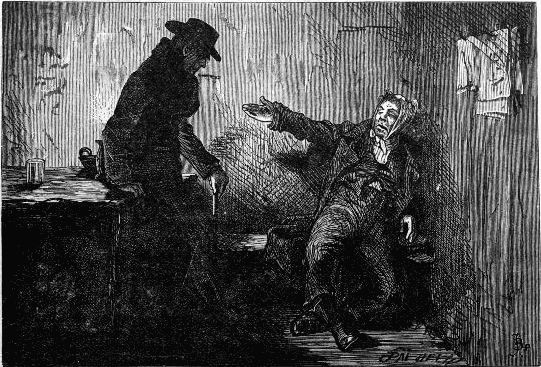

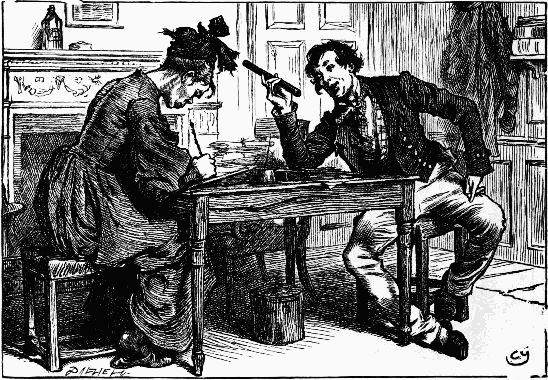

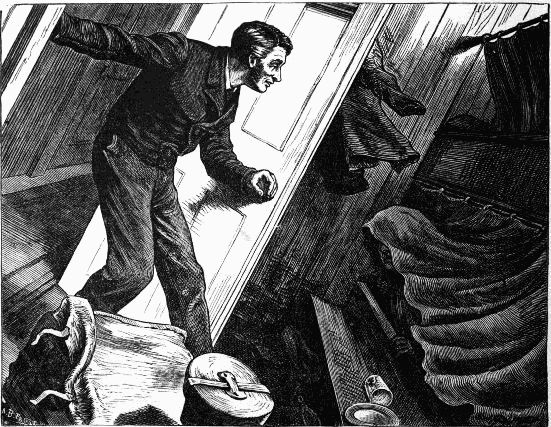

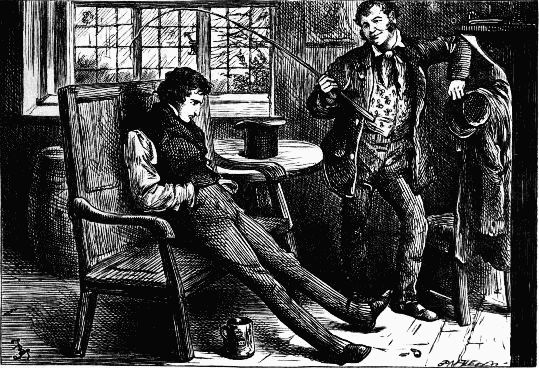

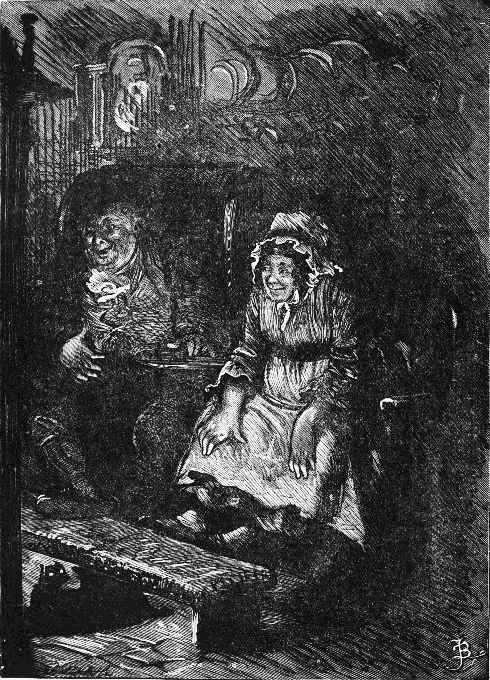

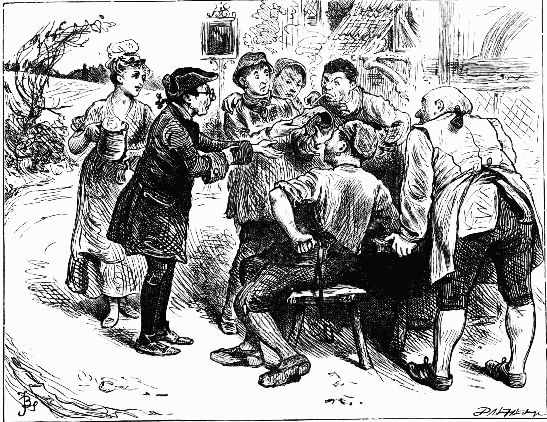

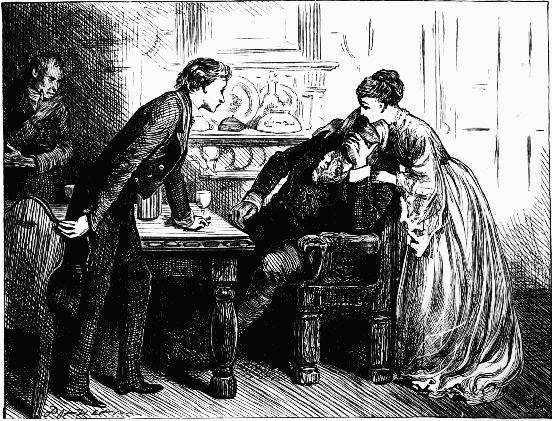

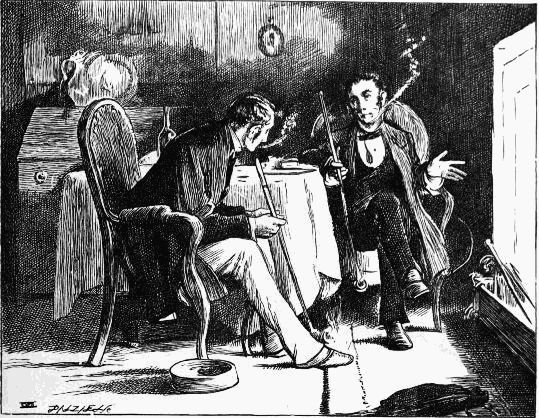

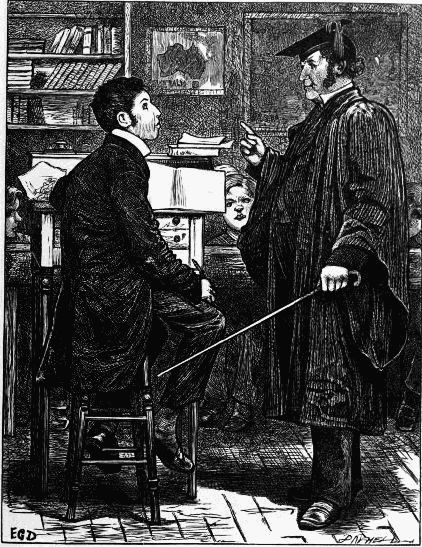

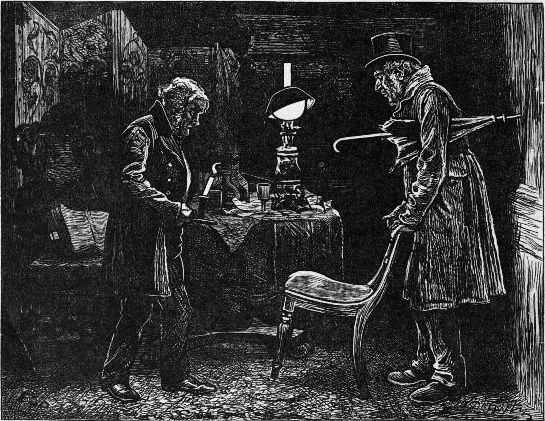

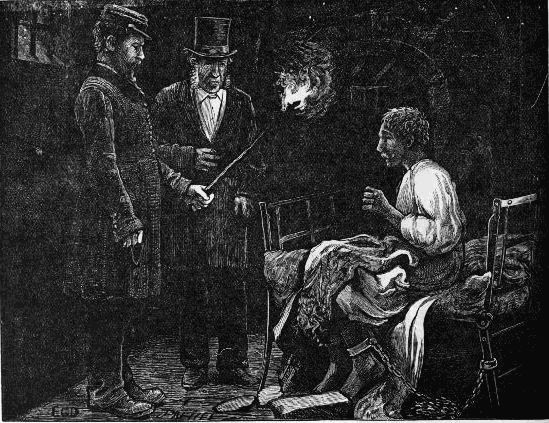

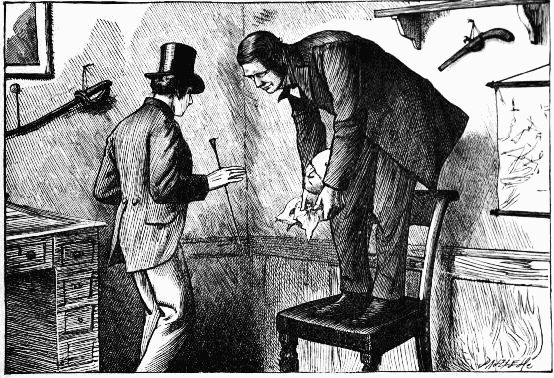

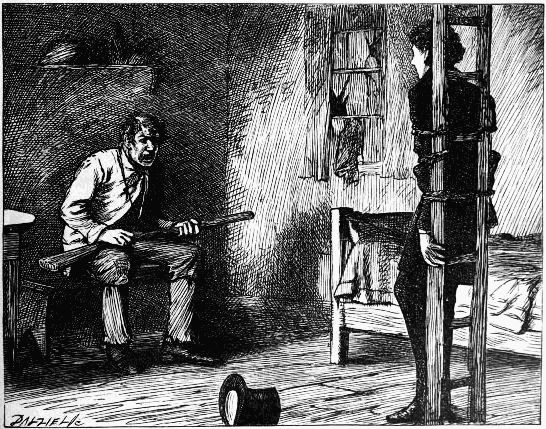

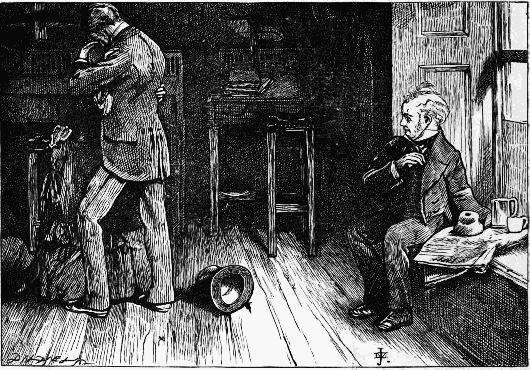

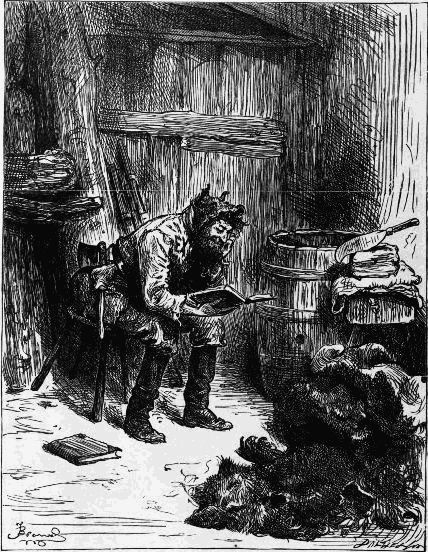

"Leave that 'ere bell alone, you wretched loo-nattic!" said the Boots,

suddenly forcing the unfortunate Trott back into his chair, and brandishing

the stick aloft—Tales, chap. viii.

"Leave that 'ere bell alone, you wretched loo-nattic!" said the Boots,

suddenly forcing the unfortunate Trott back into his chair, and brandishing

the stick aloft—Tales, chap. viii.

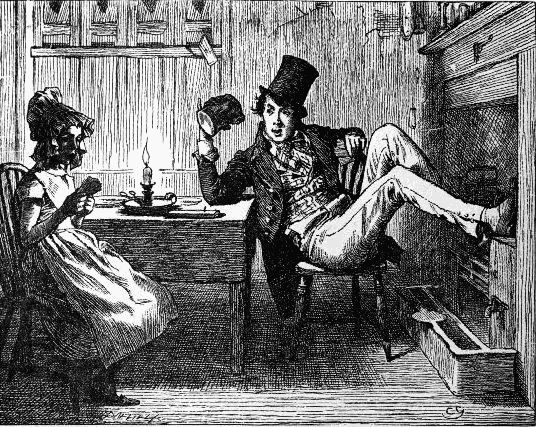

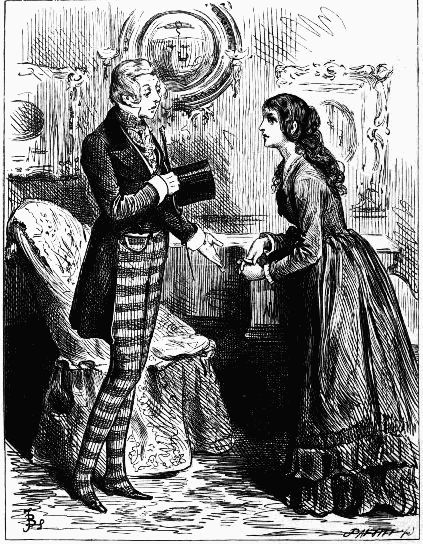

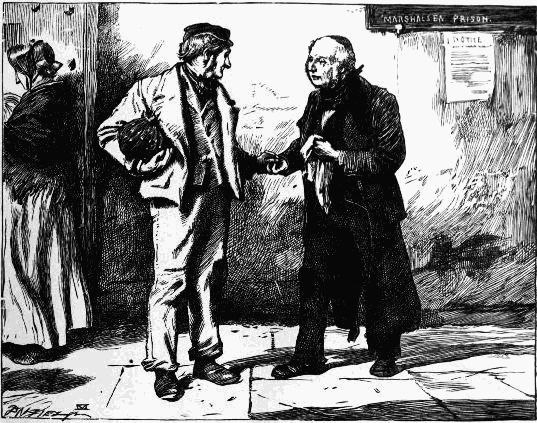

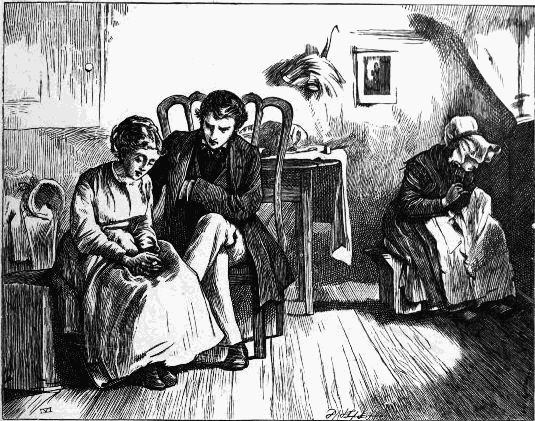

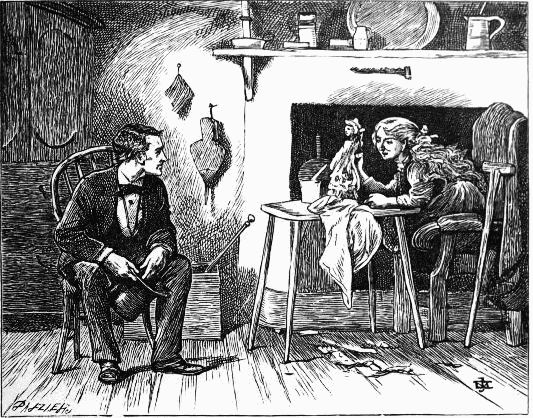

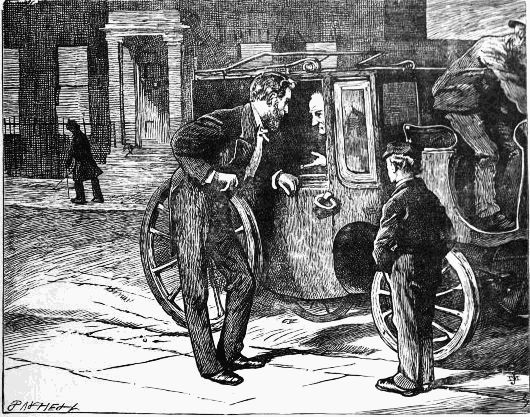

"Why," replied Mr. Walkins Tottle evasively; for he trembled violently, and felt a sudden

tingling throughout his whole frame; "Why—i should certainly—at least, i think i should

like——"—Tales, chap. x. 1

"Why," replied Mr. Walkins Tottle evasively; for he trembled violently, and felt a sudden

tingling throughout his whole frame; "Why—i should certainly—at least, i think i should

like——"—Tales, chap. x. 1

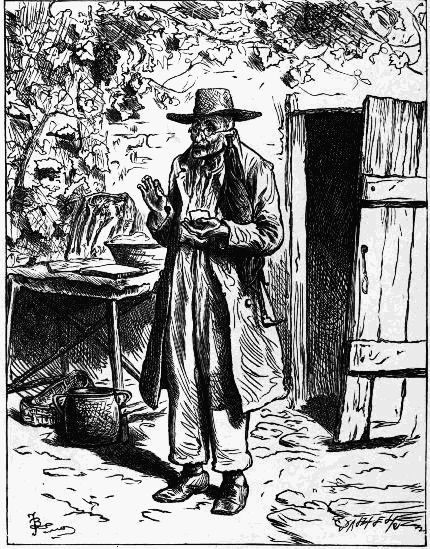

Mr. Nicodemus Dumps . . . cross, cadaverous, odd and ill-natured—Tales,

chap. xi.

Mr. Nicodemus Dumps . . . cross, cadaverous, odd and ill-natured—Tales,

chap. xi.

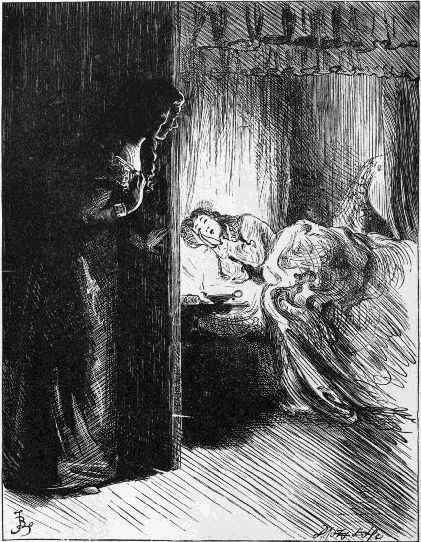

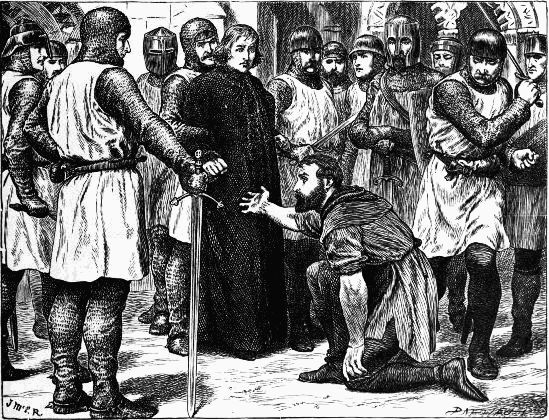

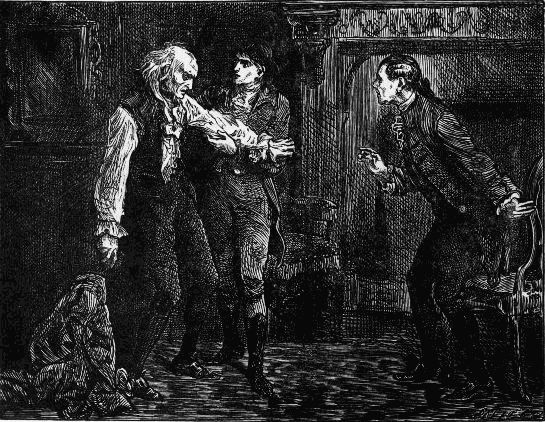

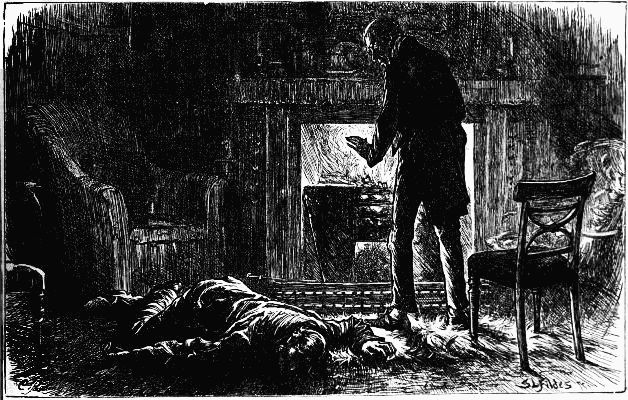

He raised his manacled hands in a threatening attitude, fixed his eyes on his shrinking

Parent and slowly left the room—Tales, chap. xii.

He raised his manacled hands in a threatening attitude, fixed his eyes on his shrinking

Parent and slowly left the room—Tales, chap. xii.

Looks that he had long forgotten were fixed upon him once more; voices

long since hushed in death sounded in his ears like the music of village

bells—Tales, chap. xii.

Looks that he had long forgotten were fixed upon him once more; voices

long since hushed in death sounded in his ears like the music of village

bells—Tales, chap. xii.

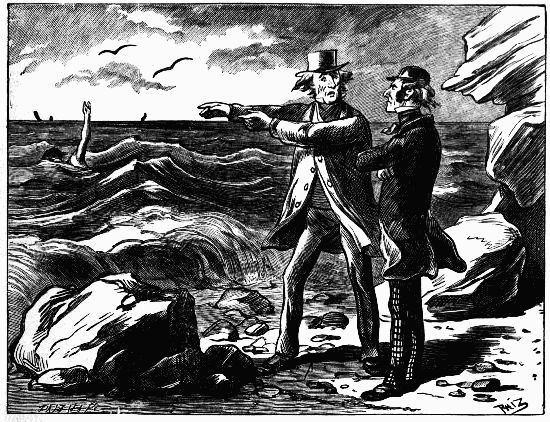

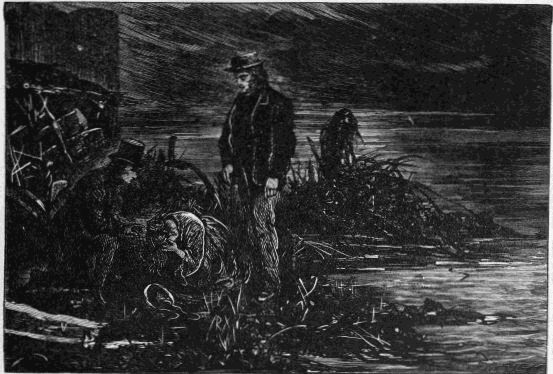

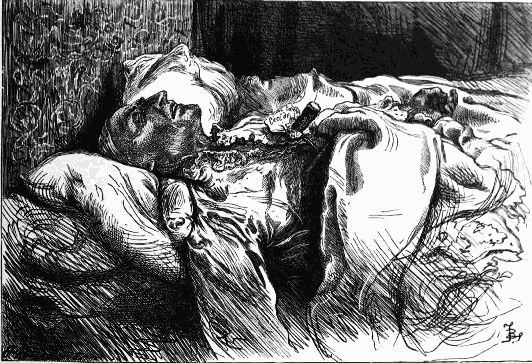

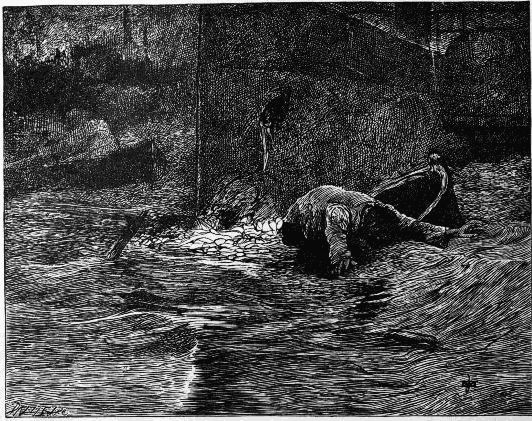

The body was washed ashore, some miles down the river, a swollen disfigured mass—Tales, chap. xii.

The body was washed ashore, some miles down the river, a swollen disfigured mass—Tales, chap. xii.

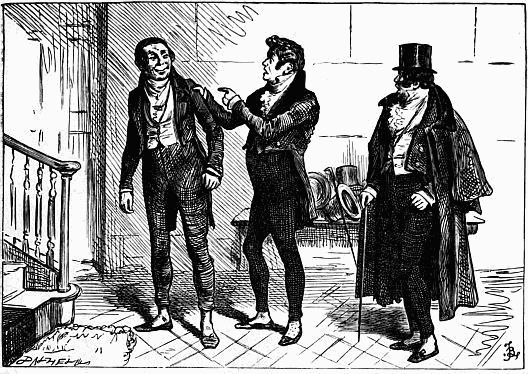

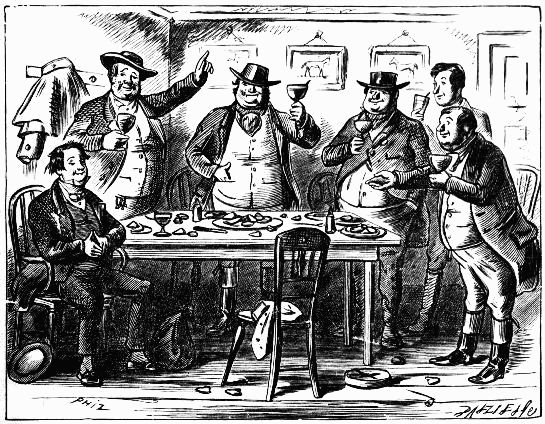

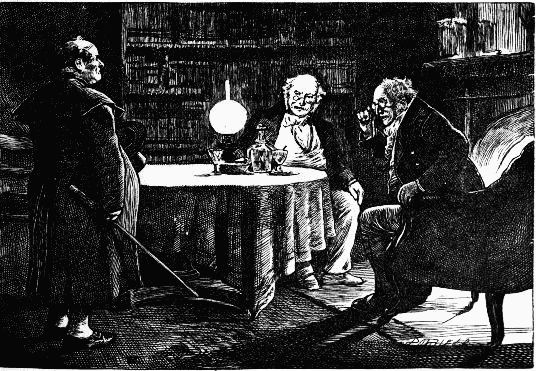

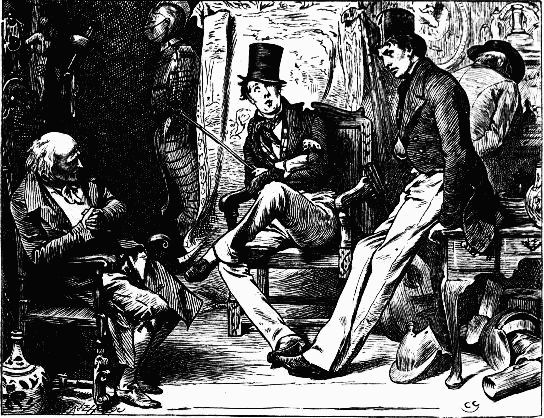

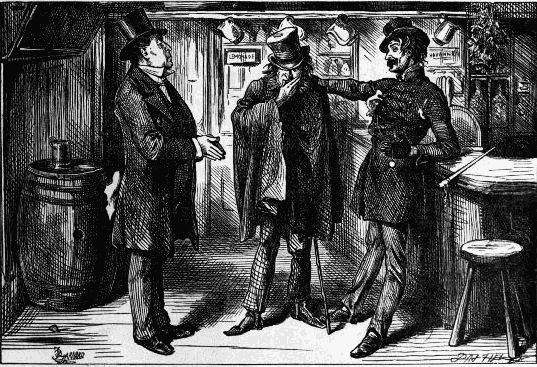

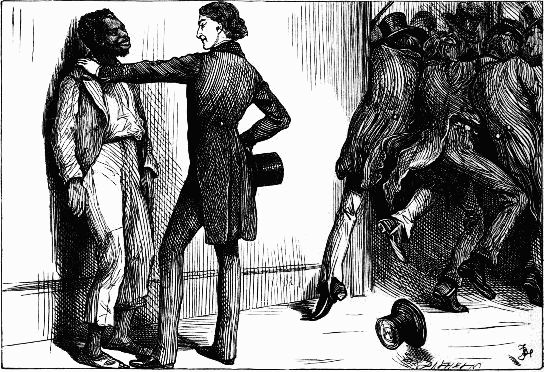

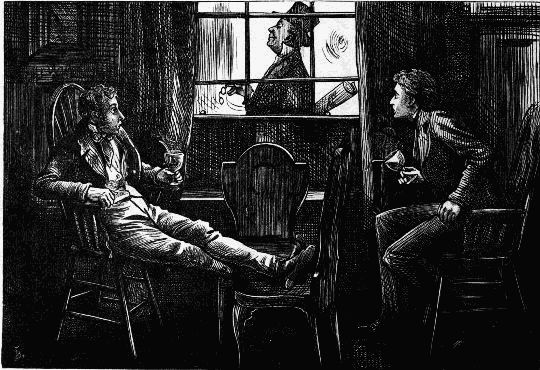

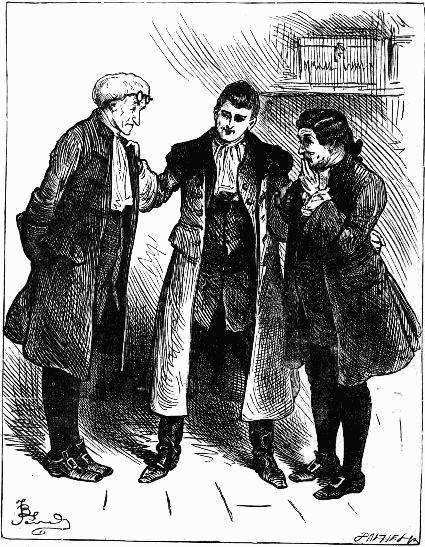

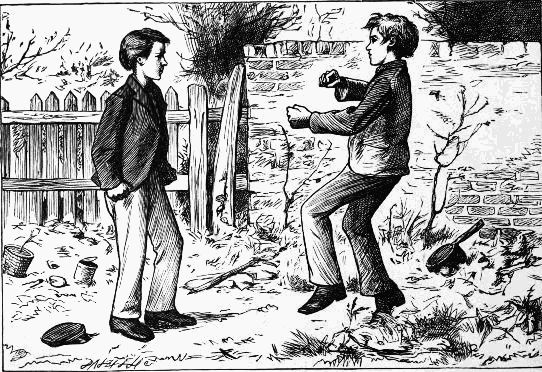

"What! introducing his friend!"—Chap. ii.

"What! introducing his friend!"—Chap. ii.

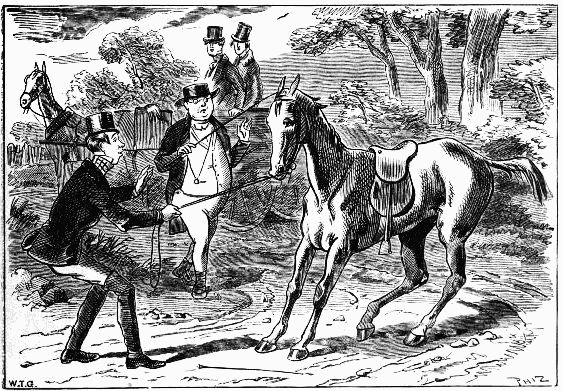

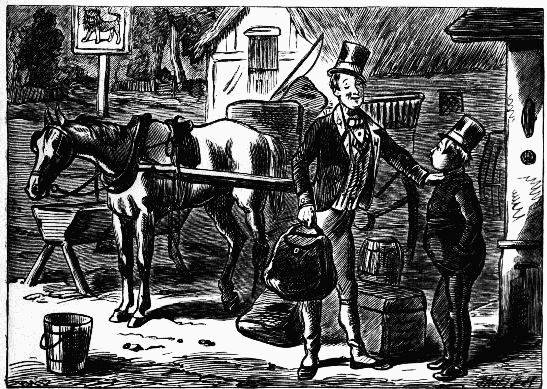

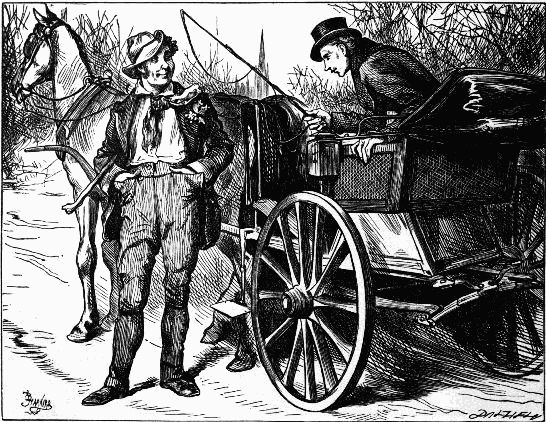

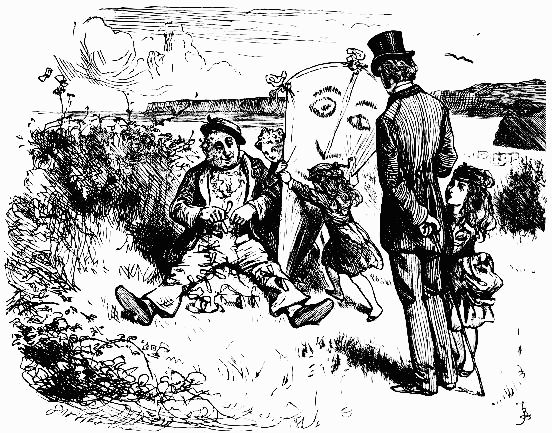

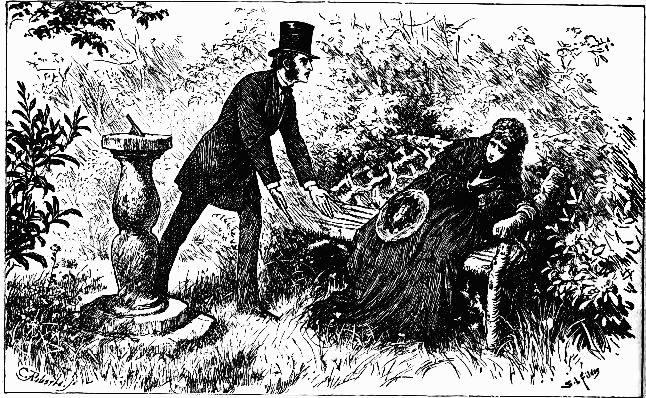

The horse no sooner beheld Mr. Pickwick advancing with the chaise whip in his hand—Chap. v.

The horse no sooner beheld Mr. Pickwick advancing with the chaise whip in his hand—Chap. v.

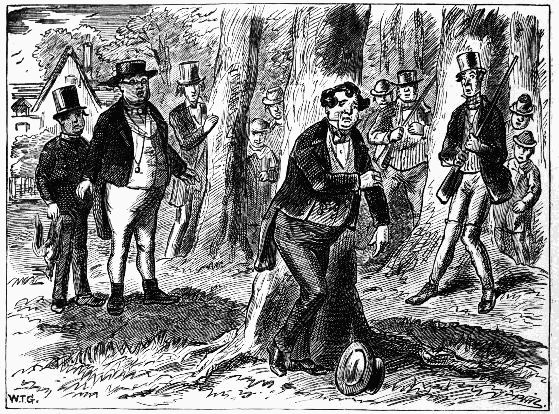

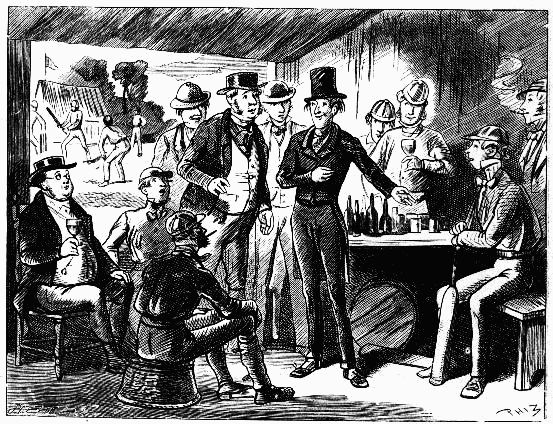

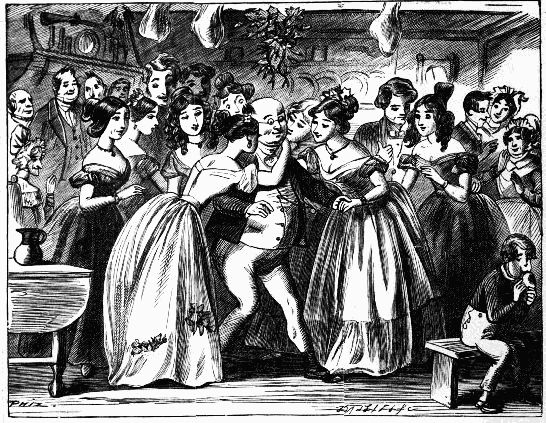

Mr. Wardle looked on, in silent wonder—Chap. vii.

Mr. Wardle looked on, in silent wonder—Chap. vii.

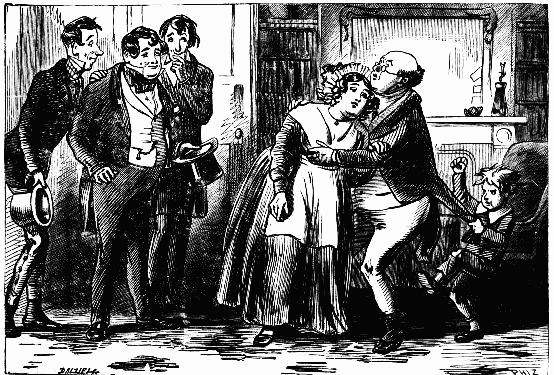

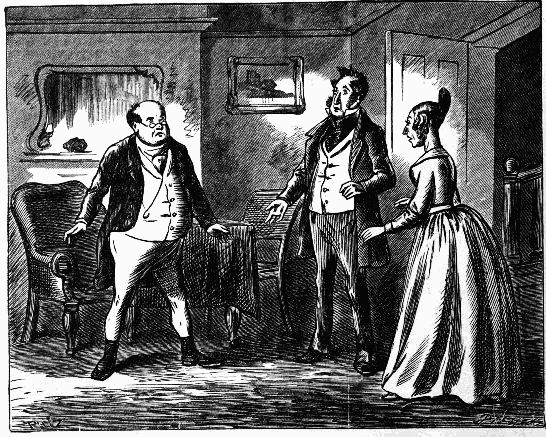

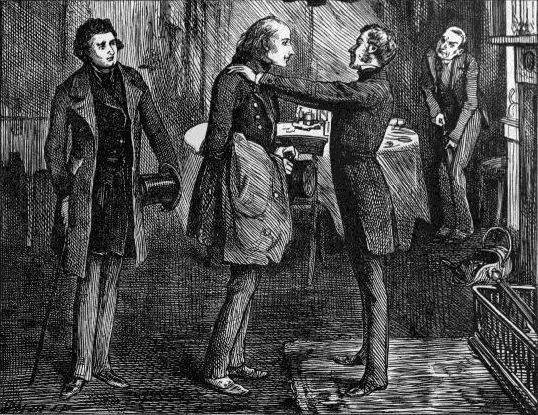

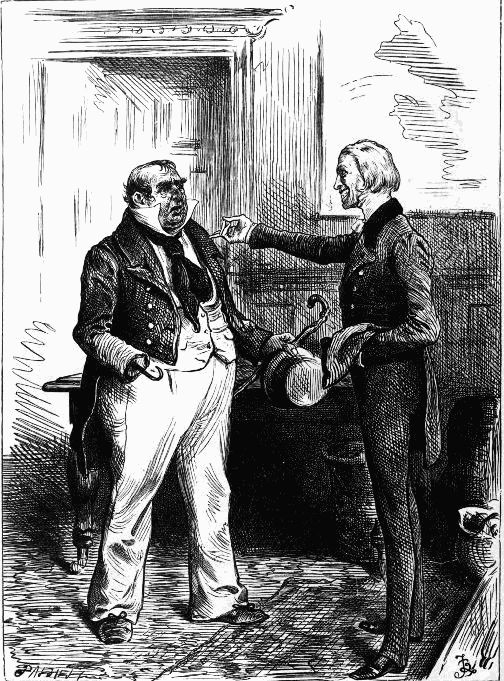

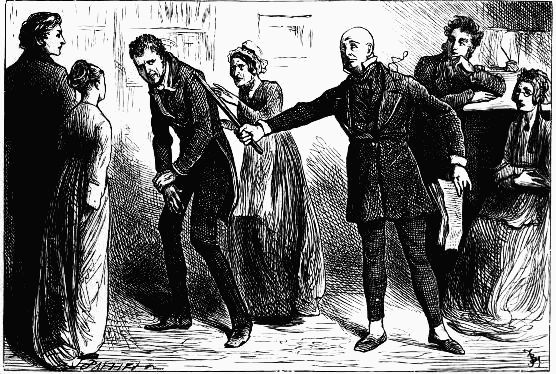

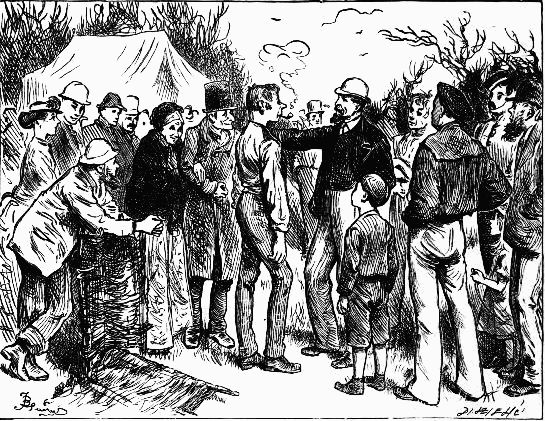

Old Mr. Wardle, with a highly-inflamed countenance, was grasping the hand of a strange gentleman—Chap. viii.

Old Mr. Wardle, with a highly-inflamed countenance, was grasping the hand of a strange gentleman—Chap. viii.

Sam stole a look at the inquirer—Chap. x.

Sam stole a look at the inquirer—Chap. x.

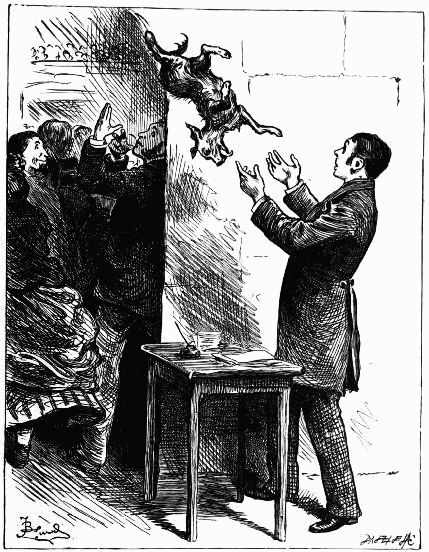

"Take this little villain away," said the agonised Mr. Pickwick—Chap. xii.

"Take this little villain away," said the agonised Mr. Pickwick—Chap. xii.

The chair was an ugly old gentleman; and what was more, he was winking at Tom Smart—Chap. xiv.

The chair was an ugly old gentleman; and what was more, he was winking at Tom Smart—Chap. xiv.

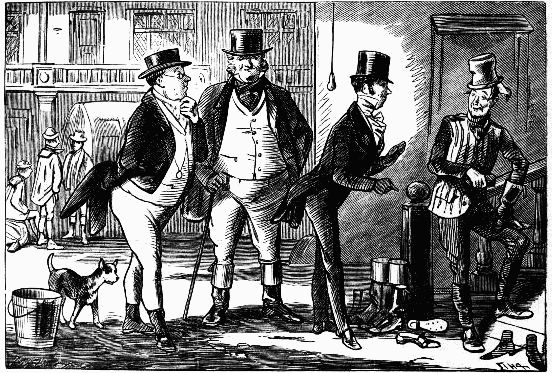

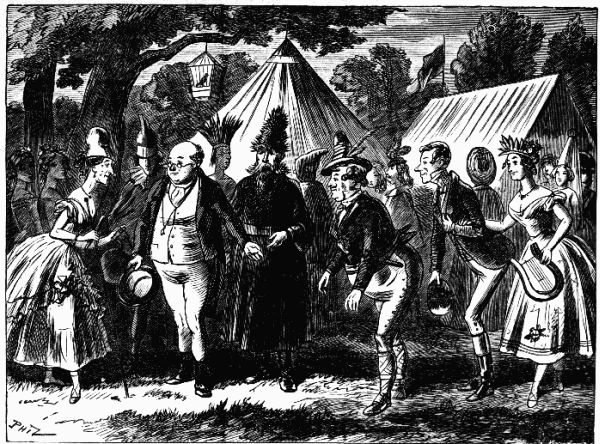

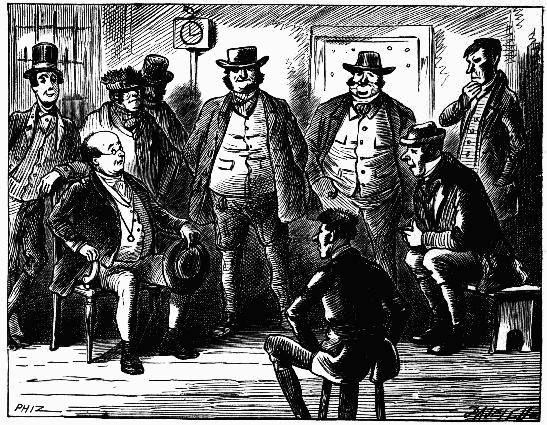

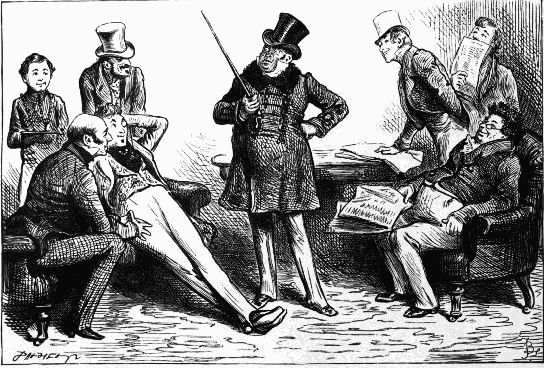

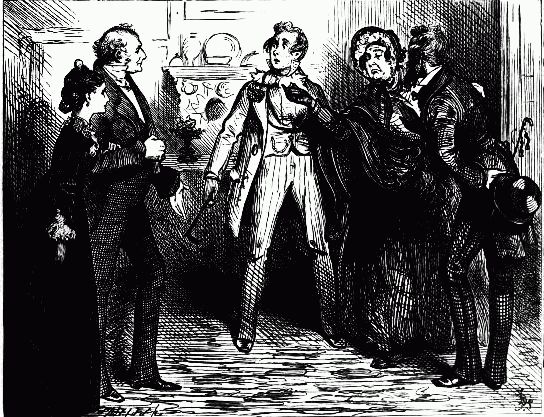

"Permit me to introduce my friends—Mr. Tupman—Mr. Winkle—Mr. Snodgrass"—Chap. xv.

"Permit me to introduce my friends—Mr. Tupman—Mr. Winkle—Mr. Snodgrass"—Chap. xv.

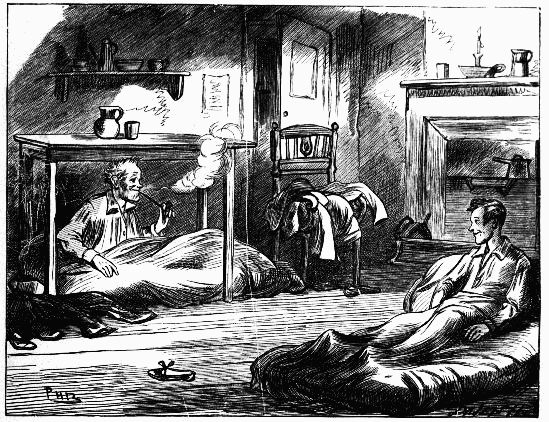

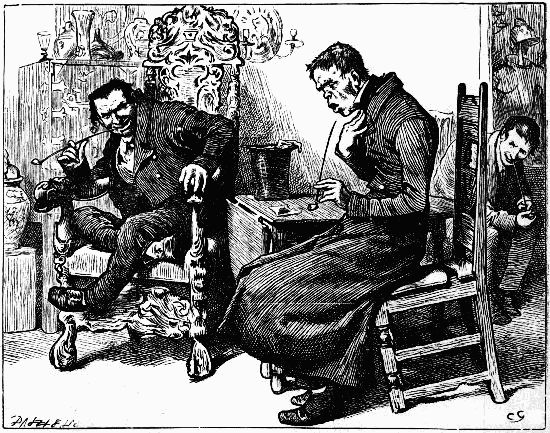

Mr. Weller was dispelling all the feverish remains of the previous evening's conviviality, . . . when

he was attracted by the appearance of a young fellow in mulberry-coloured livery—Chap. xvi.

Mr. Weller was dispelling all the feverish remains of the previous evening's conviviality, . . . when

he was attracted by the appearance of a young fellow in mulberry-coloured livery—Chap. xvi.

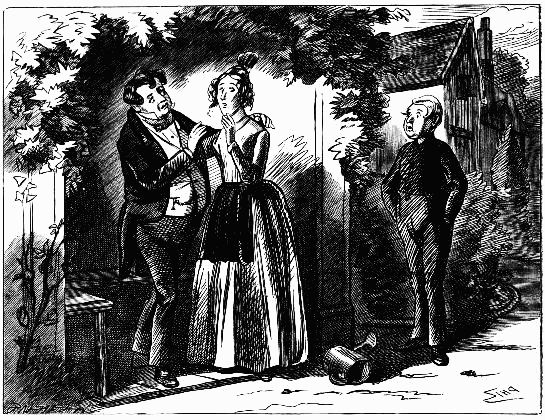

Old Lobbs gave it one tug, and open it flew, disclosing Nathaniel Pipkin standing bolt upright inside,

and shaking with apprehension from head to foot—Chap. xvii.

Old Lobbs gave it one tug, and open it flew, disclosing Nathaniel Pipkin standing bolt upright inside,

and shaking with apprehension from head to foot—Chap. xvii.

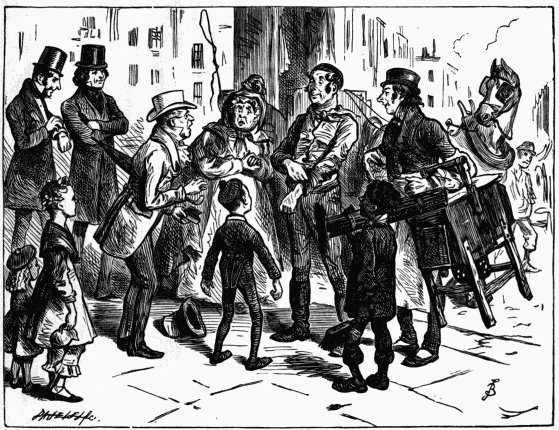

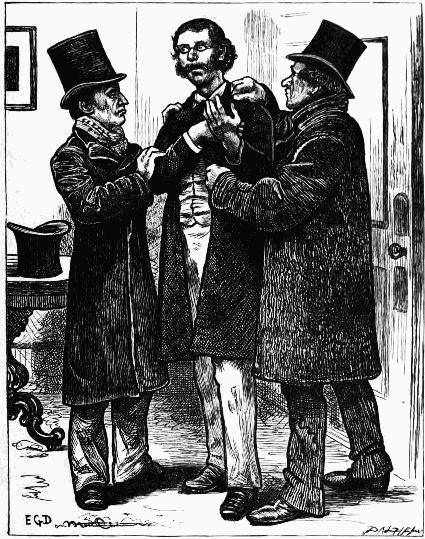

"You just come away," said Mr. Weller. "Battledore and Shuttlecock's a wery good game, when you

an't the shuttlecock and two lawyers the battledores"—Chap. xx.

"You just come away," said Mr. Weller. "Battledore and Shuttlecock's a wery good game, when you

an't the shuttlecock and two lawyers the battledores"—Chap. xx.

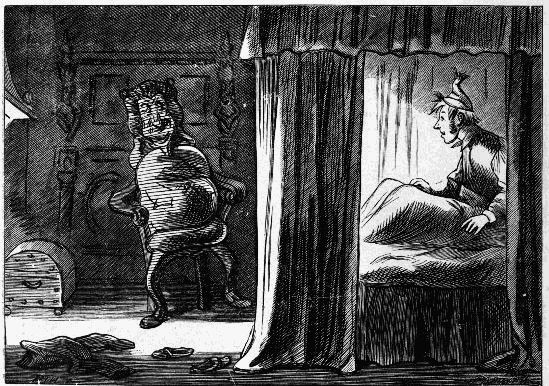

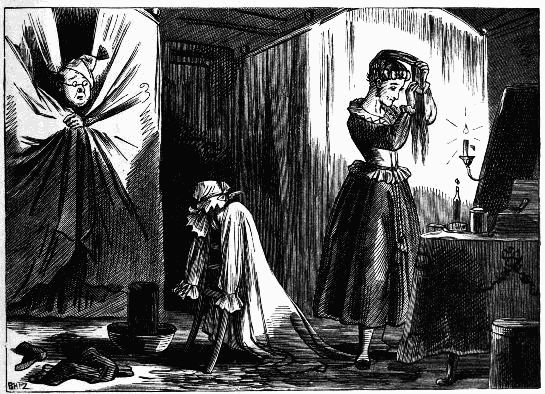

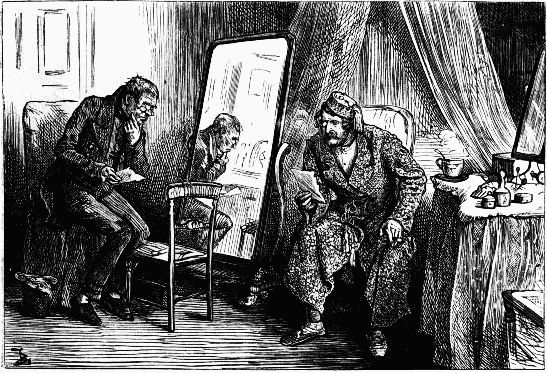

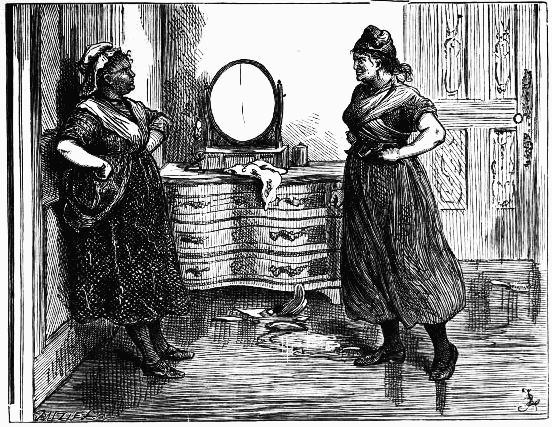

Standing before the dressing-glass was a middle-aged lady in yellow curl-papers, busily engaged in

brushing what ladies call their "back hair"—Chap. xxii.

Standing before the dressing-glass was a middle-aged lady in yellow curl-papers, busily engaged in

brushing what ladies call their "back hair"—Chap. xxii.

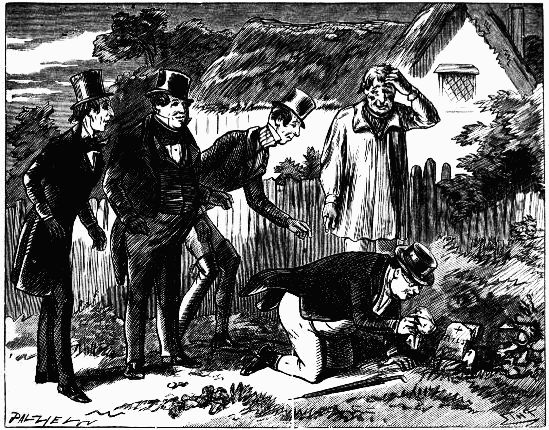

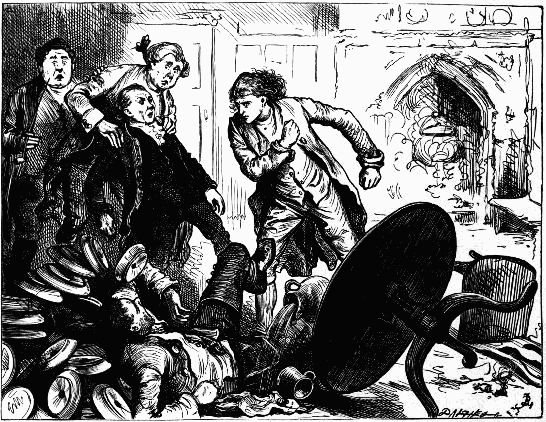

A compliment which Mr. Weller Returned by knocking him down out of hand: having previously, with

the utmost consideration, knocked down a chairman for him to lie upon—Chap. xxiv.

A compliment which Mr. Weller Returned by knocking him down out of hand: having previously, with

the utmost consideration, knocked down a chairman for him to lie upon—Chap. xxiv.

Sam looked at the fat boy with great astonishment, but without saying a word—Chap. xxviii.

Sam looked at the fat boy with great astonishment, but without saying a word—Chap. xxviii.

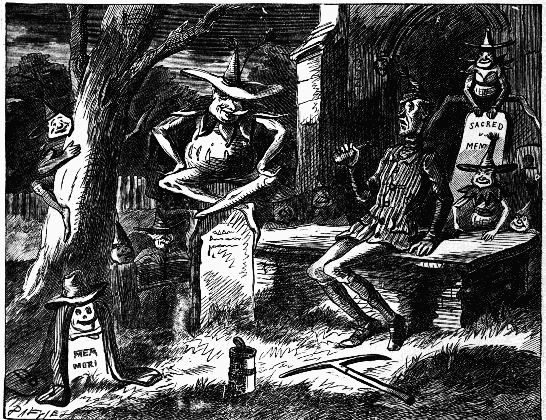

Seated on an upright tombstone, close to him, was a strange unearthly figure—Chap. xxix.

Seated on an upright tombstone, close to him, was a strange unearthly figure—Chap. xxix.

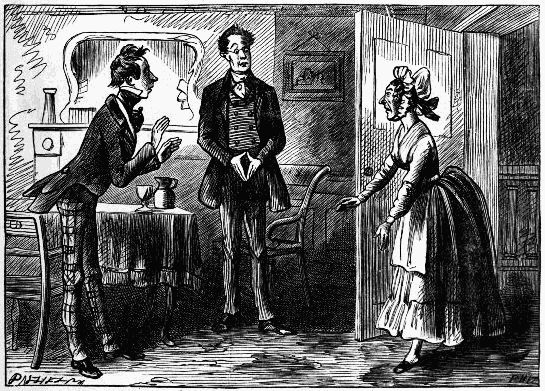

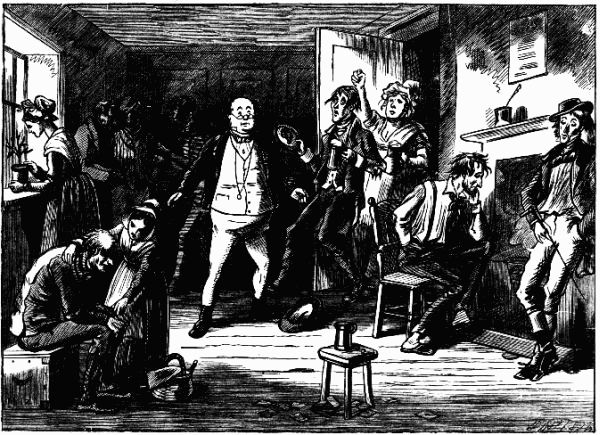

A little fierce woman bounced into the room, all in a tremble with passion, and pale with rage—Chap. xxxii.

A little fierce woman bounced into the room, all in a tremble with passion, and pale with rage—Chap. xxxii.

Before Sam could interfere to prevent it, his heroic parent had penetrated into a remote corner of

the room, and attacked the Reverend Mr. Stiggins with manual dexterity—Chap. xxxiii.

Before Sam could interfere to prevent it, his heroic parent had penetrated into a remote corner of

the room, and attacked the Reverend Mr. Stiggins with manual dexterity—Chap. xxxiii.

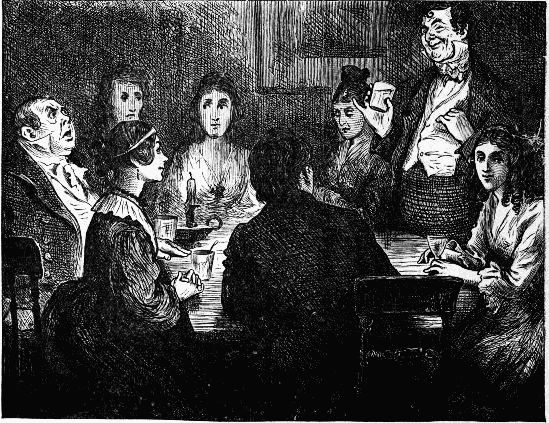

Poor Mr. Pickwick! he had never played with three thorough-paced female card-players before—Chap. xxxv.

Poor Mr. Pickwick! he had never played with three thorough-paced female card-players before—Chap. xxxv.

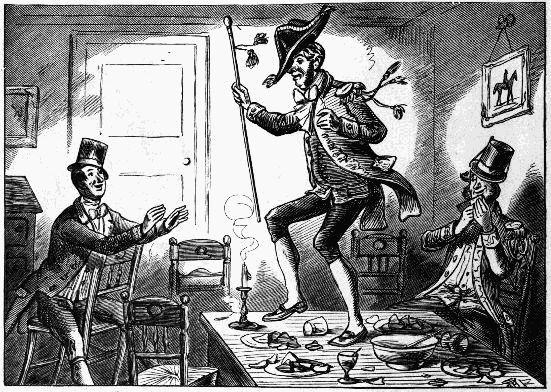

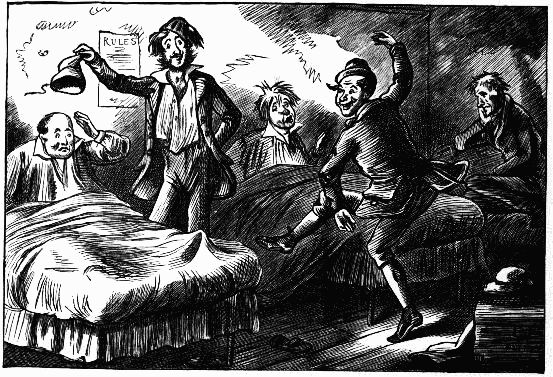

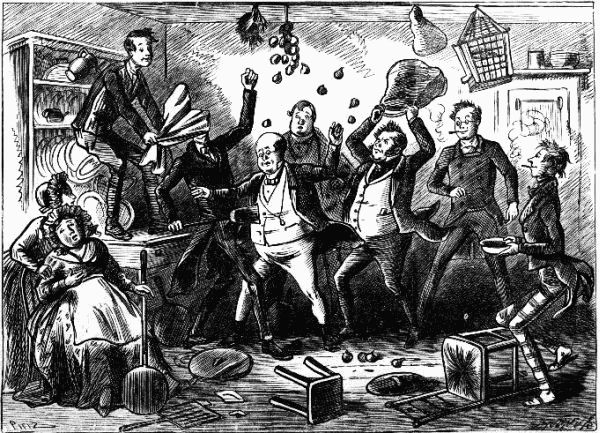

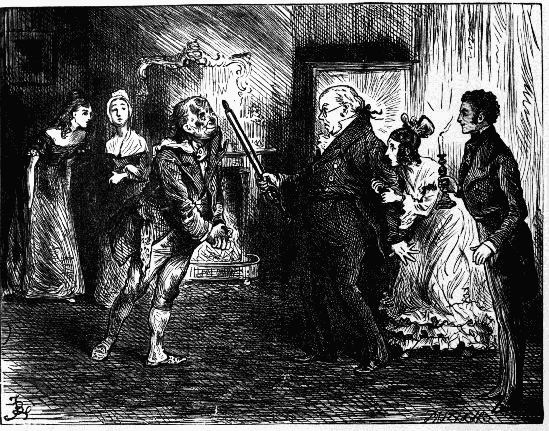

Mr. Tuckle, dressed out with the cocked-hat and stick, danced the frog hornpipe among the shells on

the table—Chap. xxxvii.

Mr. Tuckle, dressed out with the cocked-hat and stick, danced the frog hornpipe among the shells on

the table—Chap. xxxvii.

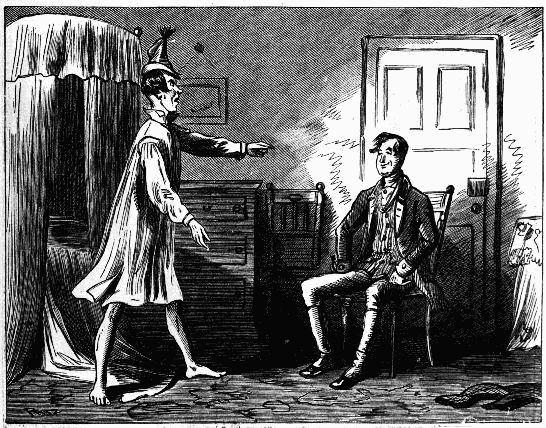

"Unlock that door, and leave this room immediately, sir," said Mr. Winkle—Chap. xxxviii.

"Unlock that door, and leave this room immediately, sir," said Mr. Winkle—Chap. xxxviii.

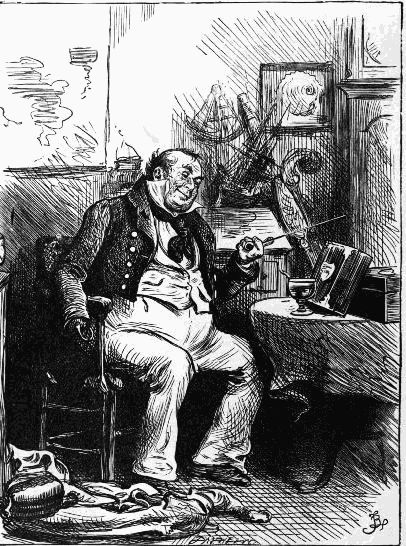

Mr. Pickwick sitting for his portrait—Chap. xl.

Mr. Pickwick sitting for his portrait—Chap. xl.

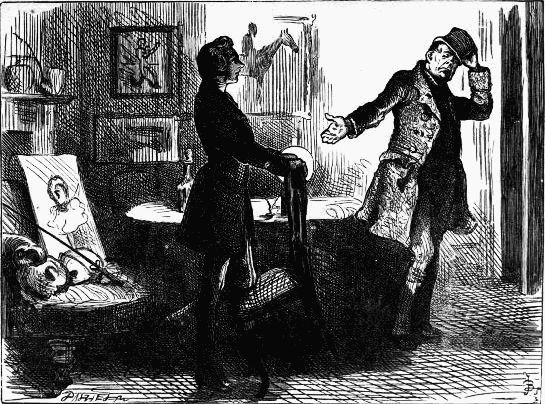

Letting his hat fall on the floor, he stood perfectly fixed and immovable with astonishment—Chap. xlii.

Letting his hat fall on the floor, he stood perfectly fixed and immovable with astonishment—Chap. xlii.

Sam, having been formally introduced . . . . as the offspring of Mr. Weller, of the Belle Savage, was

treated with marked distinction—Chap. xliii.

Sam, having been formally introduced . . . . as the offspring of Mr. Weller, of the Belle Savage, was

treated with marked distinction—Chap. xliii.

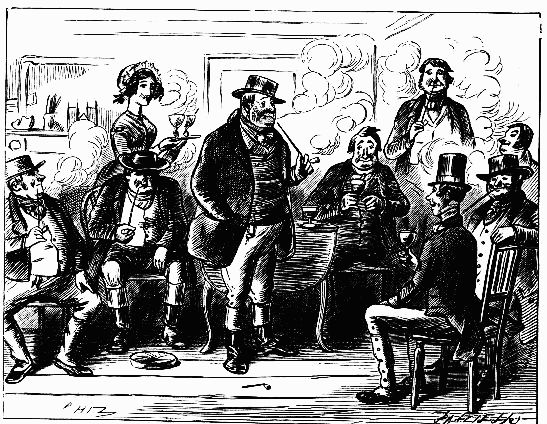

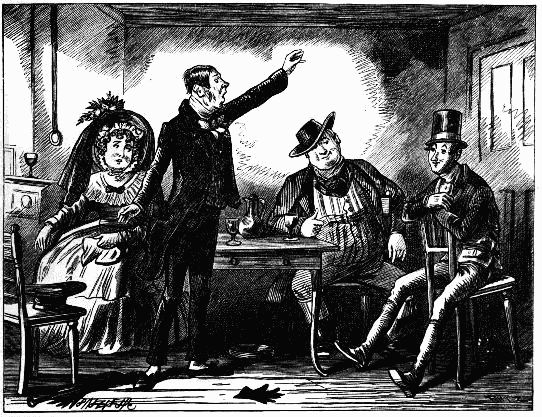

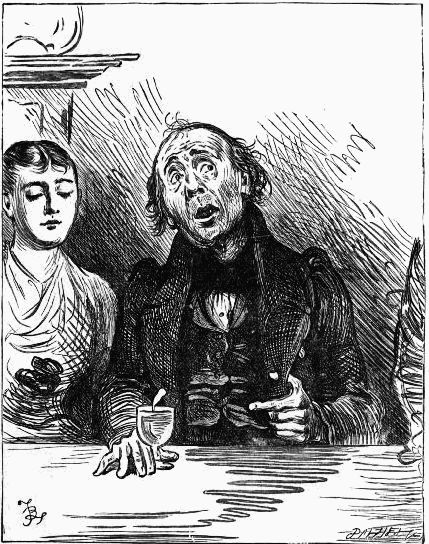

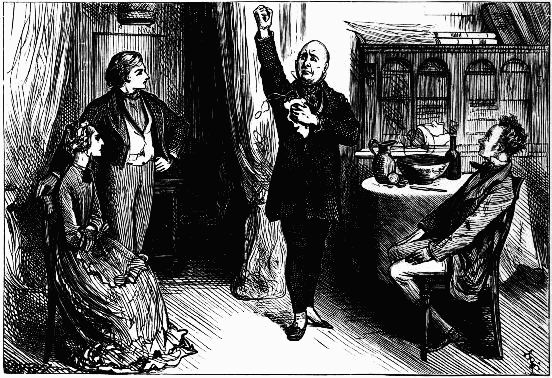

Mr. Stiggins, getting on his legs as well as he could, proceeded to deliver an edifying discourse for

the benefit of the company—Chap. xlv.

Mr. Stiggins, getting on his legs as well as he could, proceeded to deliver an edifying discourse for

the benefit of the company—Chap. xlv.

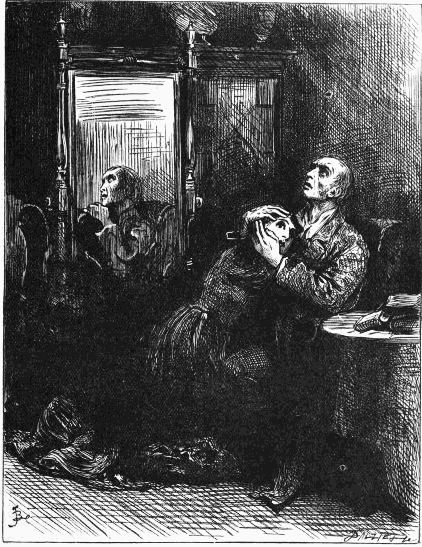

Mr. Pickwick could scarcely believe the evidence of his own senses—Chap. xlvii.

Mr. Pickwick could scarcely believe the evidence of his own senses—Chap. xlvii.

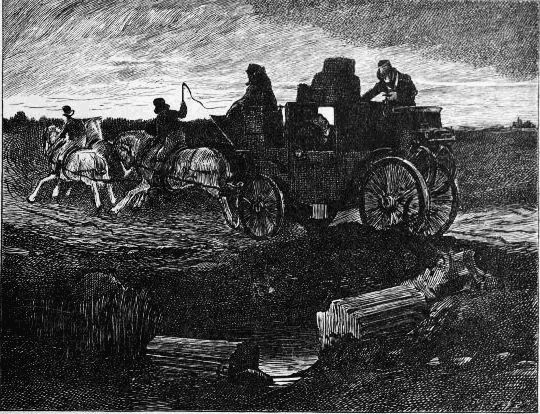

Mr. Bob Sawyer was seated: not in the dickey, but on the roof of the chaise—Chap. l.

Mr. Bob Sawyer was seated: not in the dickey, but on the roof of the chaise—Chap. l.

Snatching up a meal-sack, effectually stopped the conflict by drawing it over the head and shoulders of the mighty Pott—Chap. ii.

Snatching up a meal-sack, effectually stopped the conflict by drawing it over the head and shoulders of the mighty Pott—Chap. ii.

It was a still more exciting spectacle to behold Mr. Weller . . . . immersing Mr. Stiggins's head in

a horse-trough full of water, and holding it there until he was half suffocated—Chap. lii.

It was a still more exciting spectacle to behold Mr. Weller . . . . immersing Mr. Stiggins's head in

a horse-trough full of water, and holding it there until he was half suffocated—Chap. lii.

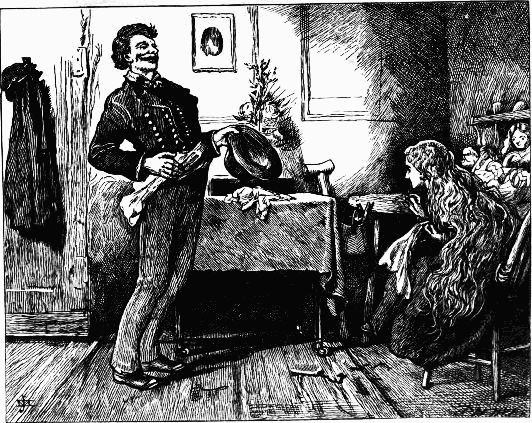

"I say, how nice you look!"—Chap. liv.

"I say, how nice you look!"—Chap. liv.

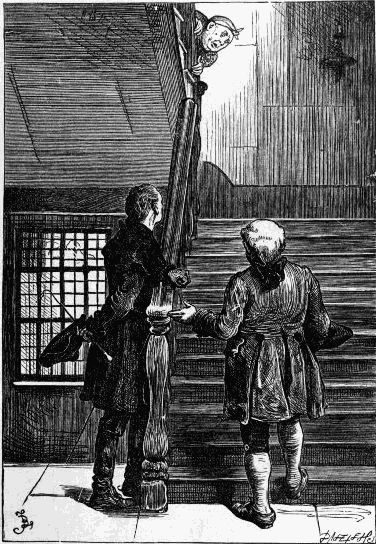

The words were scarcely out of the old gentleman's lips, when footsteps were heard ascending the

stairs—Chap. lvi.

The words were scarcely out of the old gentleman's lips, when footsteps were heard ascending the

stairs—Chap. lvi.

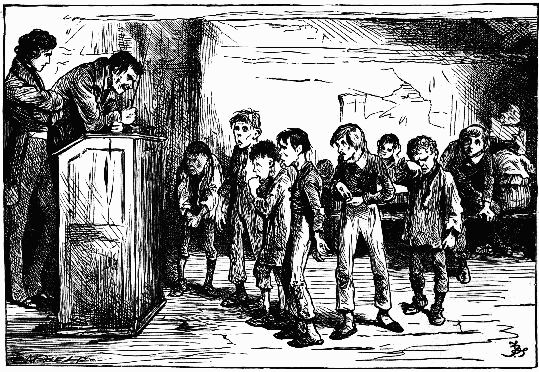

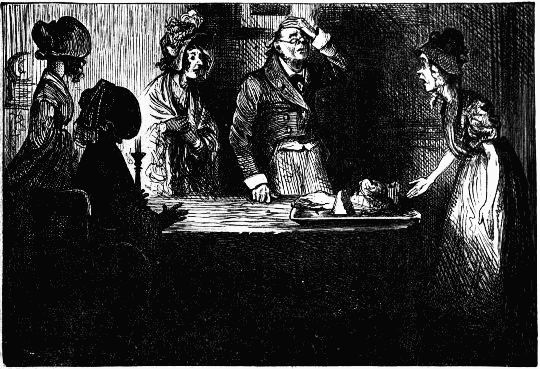

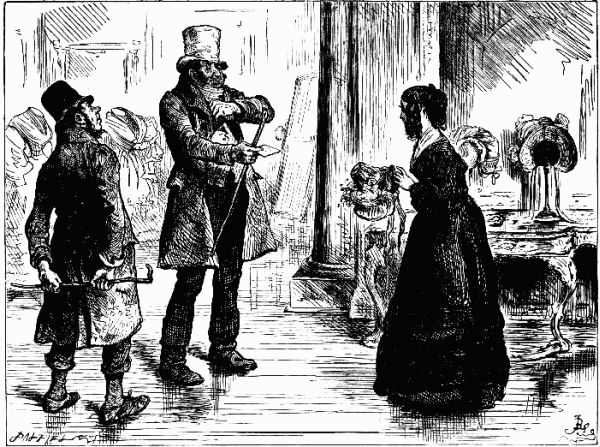

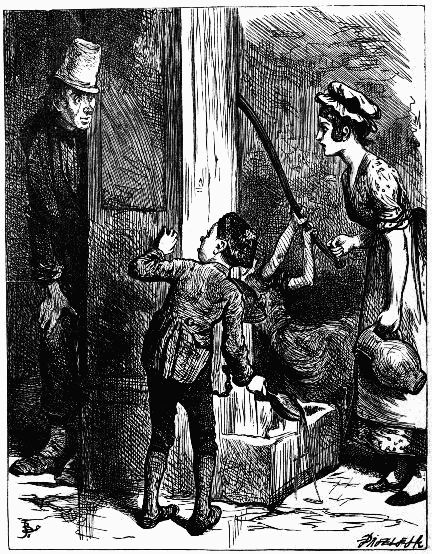

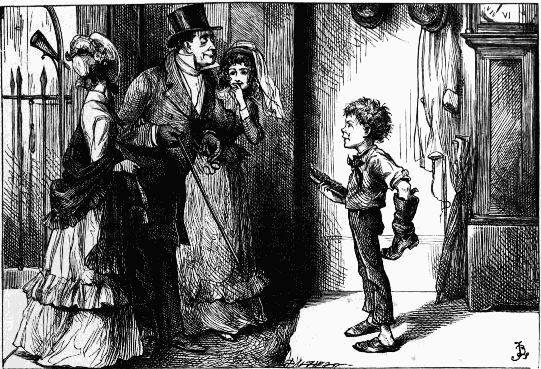

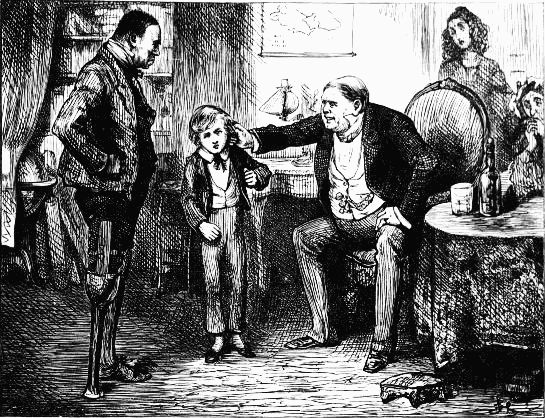

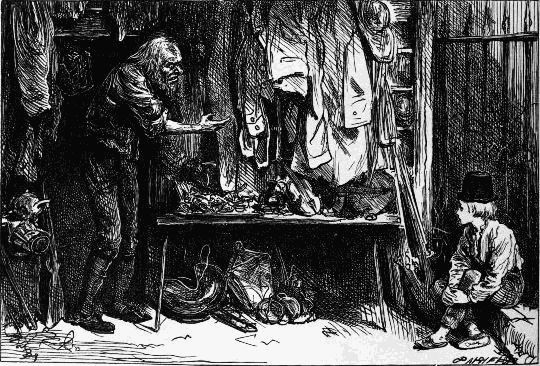

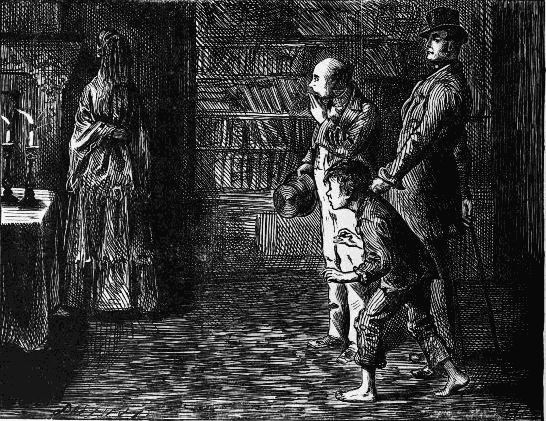

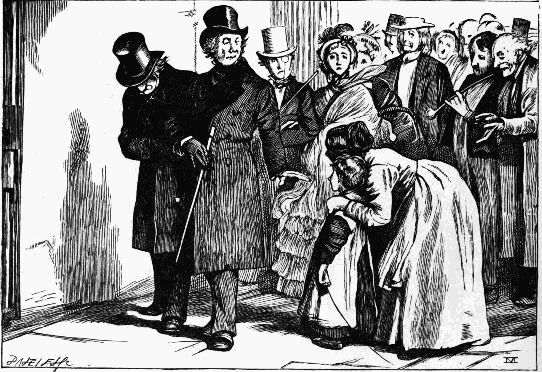

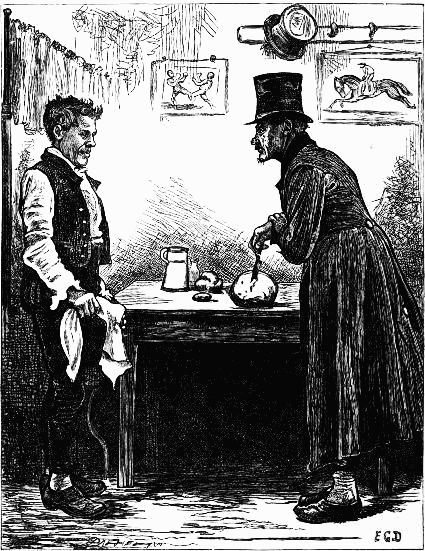

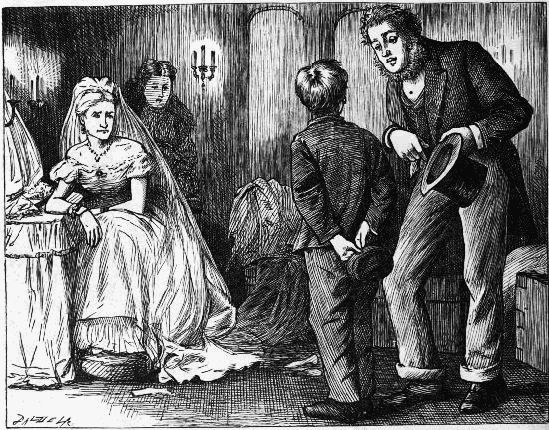

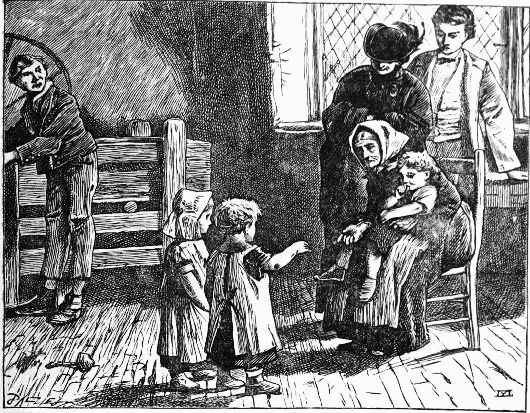

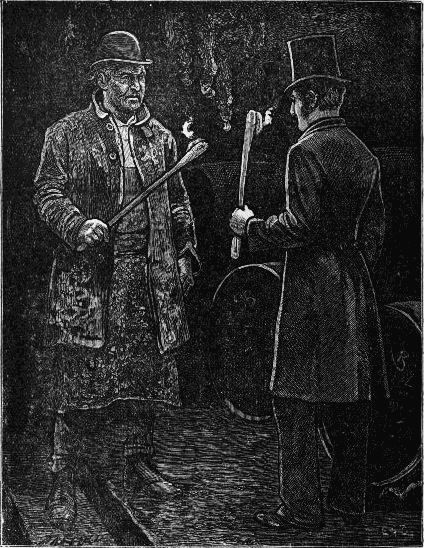

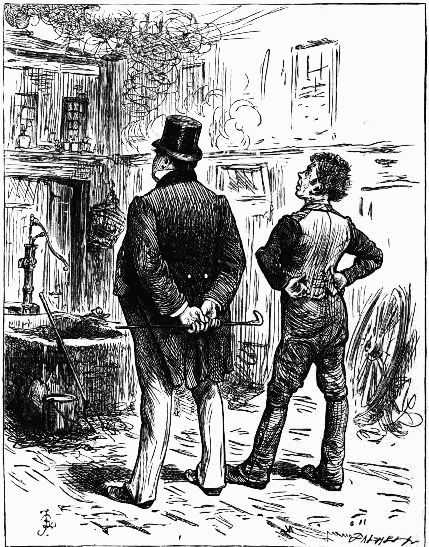

"Liberal terms, Mr. Sowerberry, liberal terms!"—Chap. iv.

"Liberal terms, Mr. Sowerberry, liberal terms!"—Chap. iv.

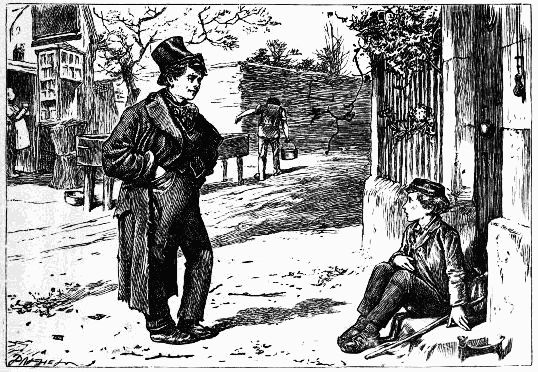

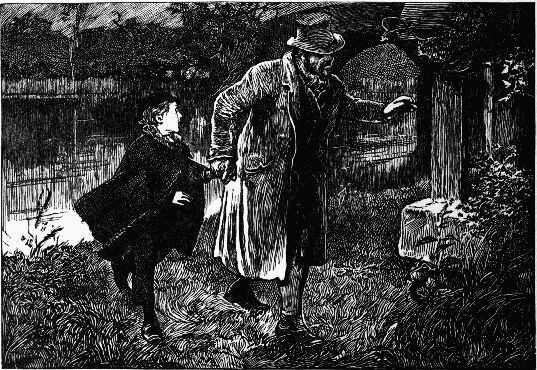

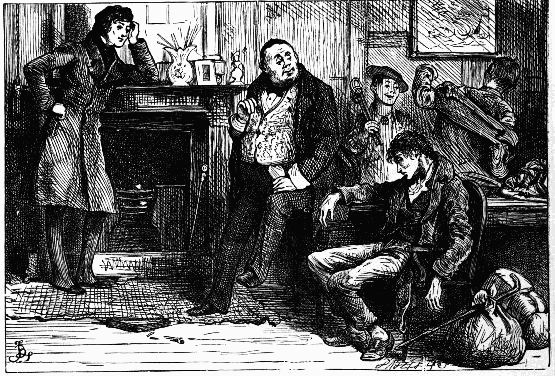

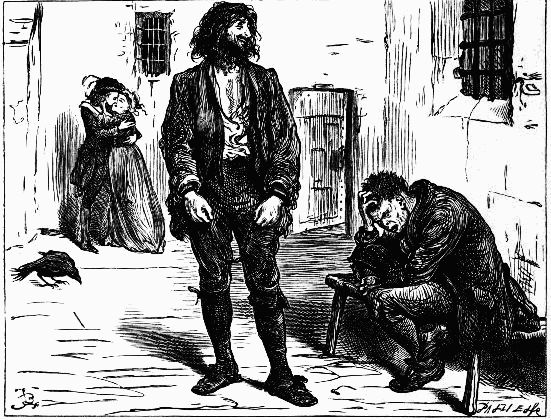

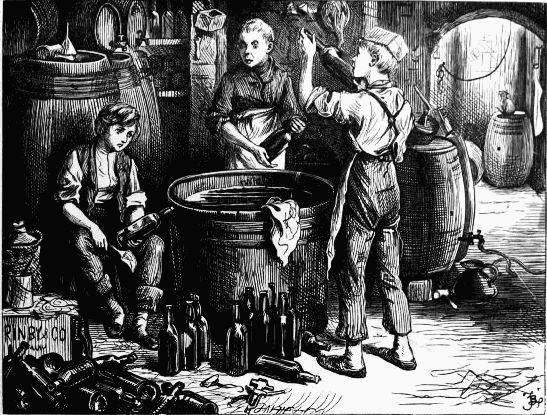

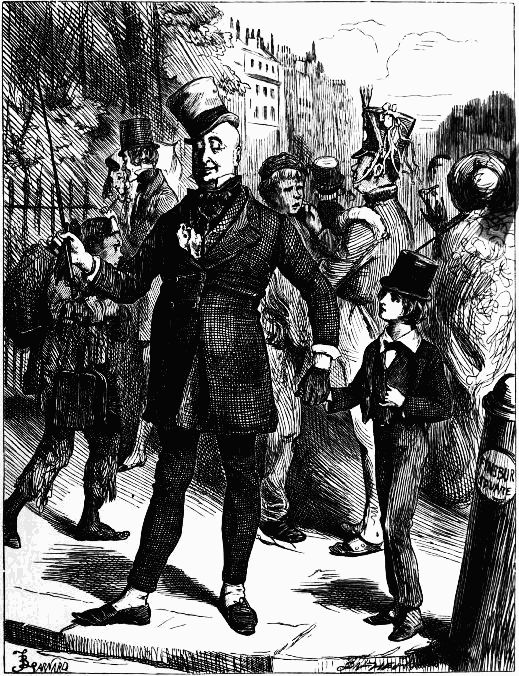

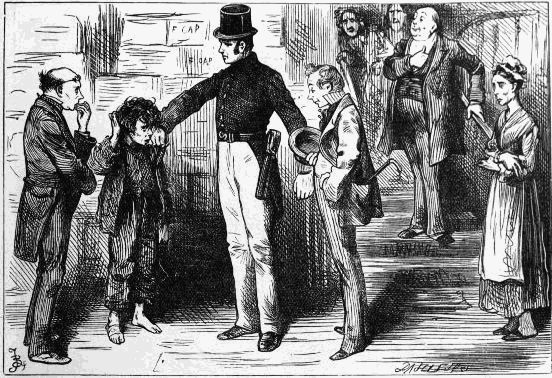

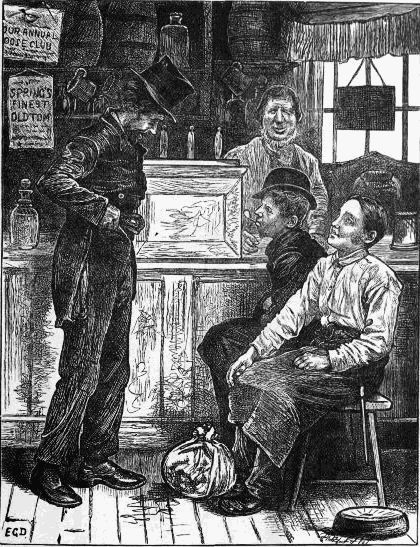

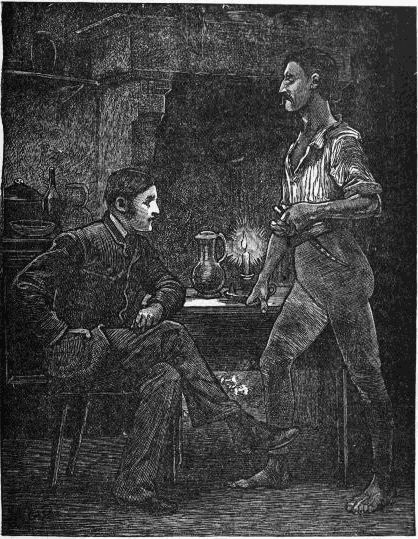

"Hullo, my covey! What's the row?"—Chap. viii.

"Hullo, my covey! What's the row?"—Chap. viii.

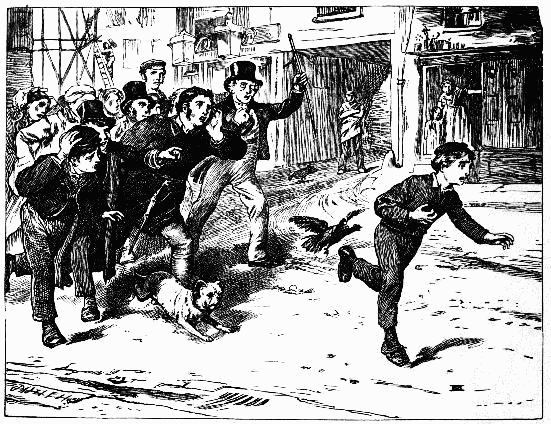

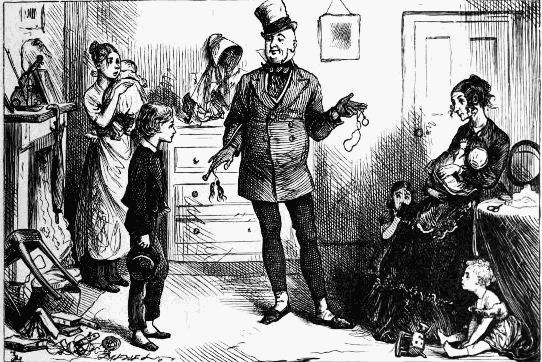

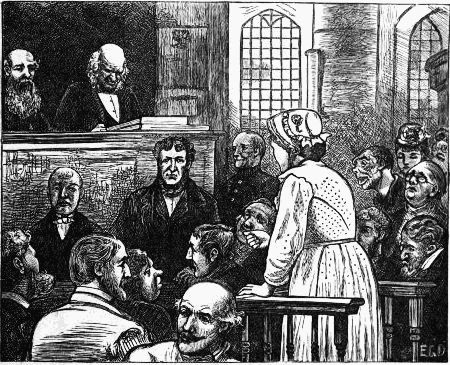

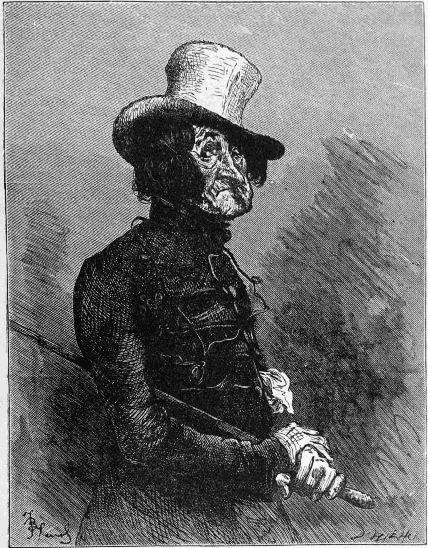

"A beadle! A parish beadle, or I'll eat my head"—Chap. xvii.

"A beadle! A parish beadle, or I'll eat my head"—Chap. xvii.

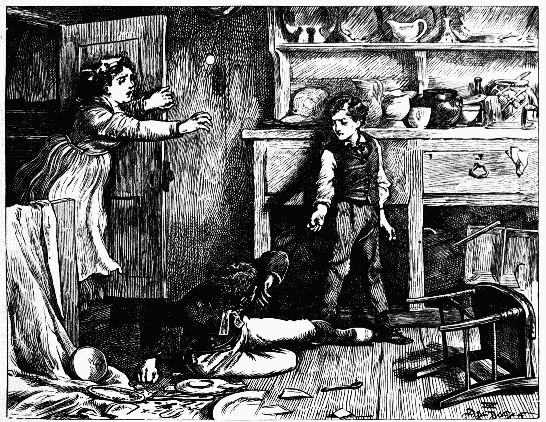

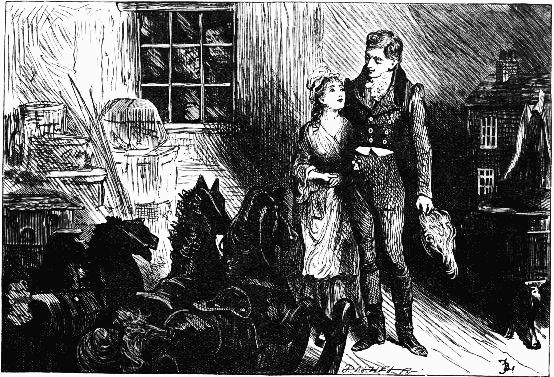

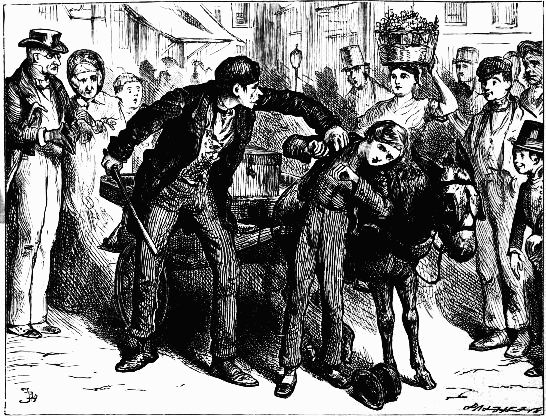

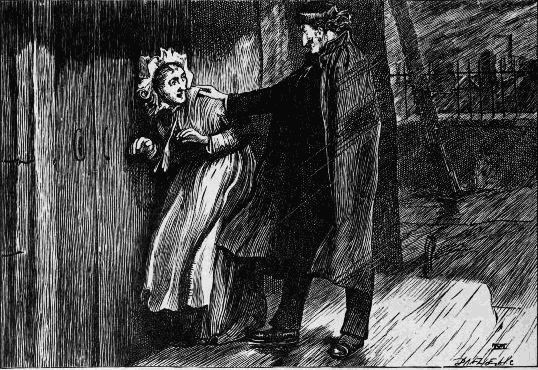

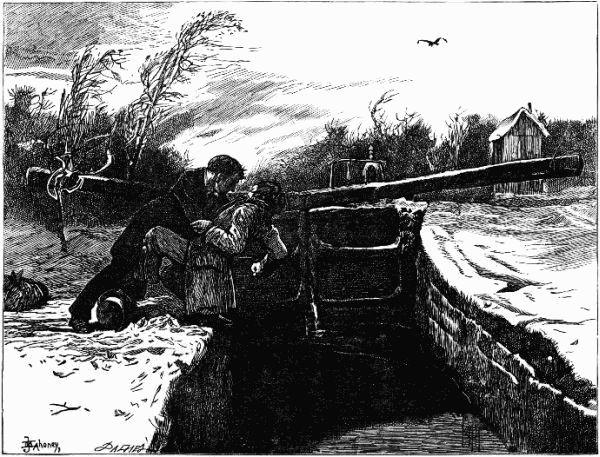

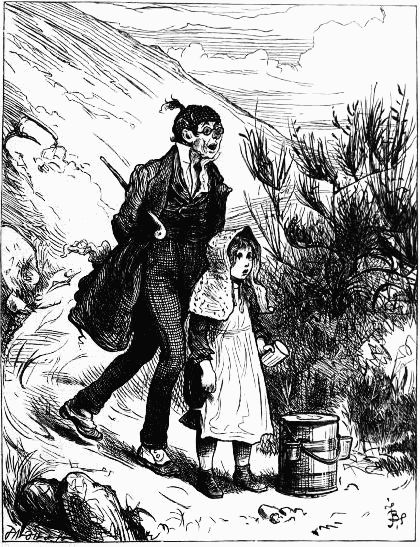

Sikes, with Oliver's hands still in his, softly approached the low porch—Chap. xxi.

Sikes, with Oliver's hands still in his, softly approached the low porch—Chap. xxi.

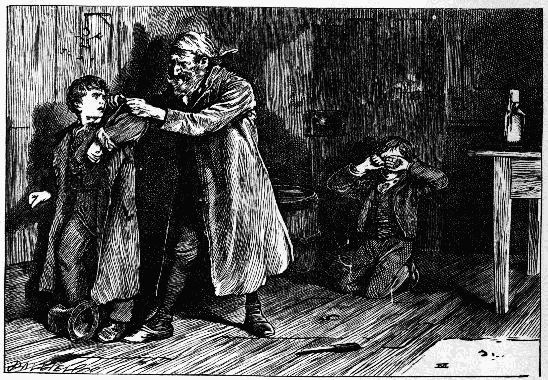

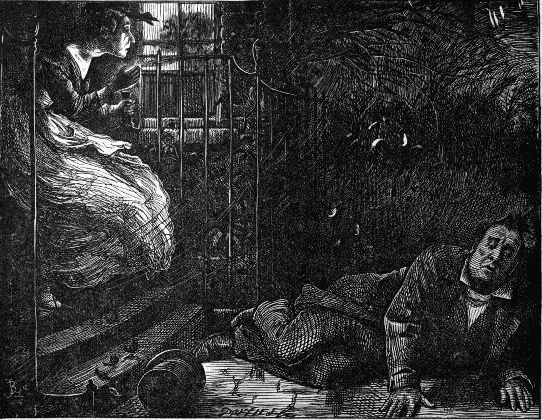

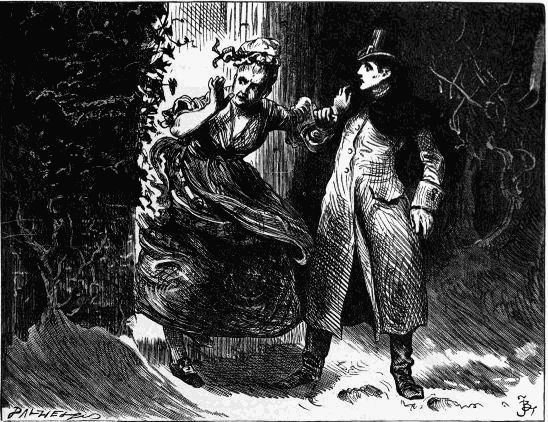

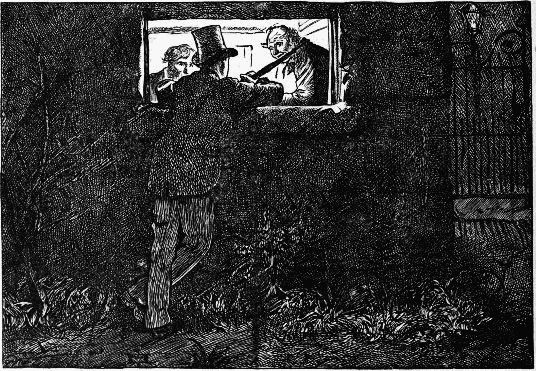

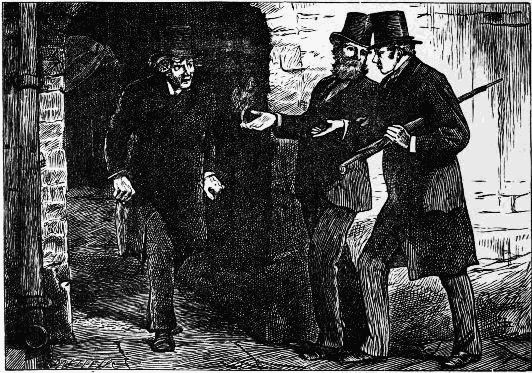

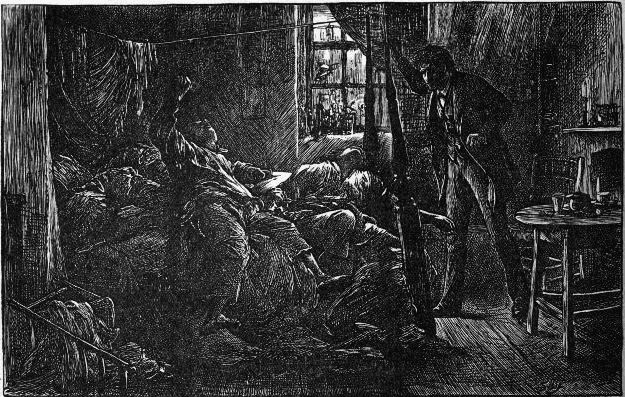

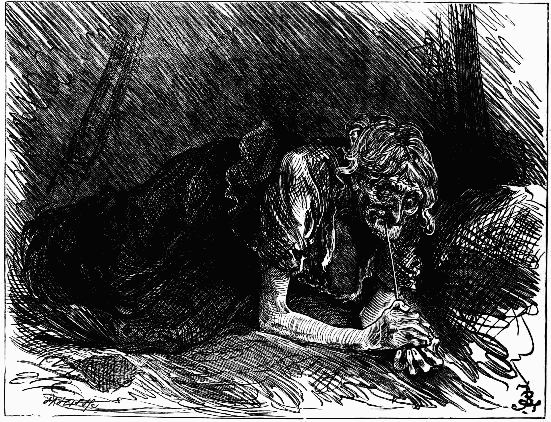

"Fagin!" whispered a voice close to his ear—Chap. xxvi.

"Fagin!" whispered a voice close to his ear—Chap. xxvi.

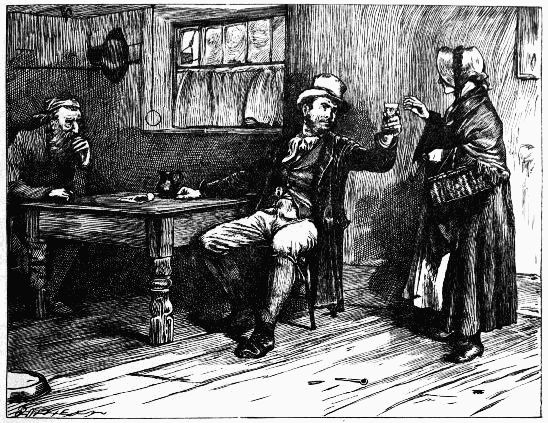

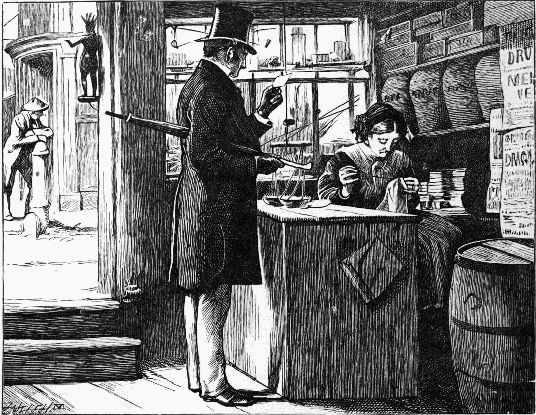

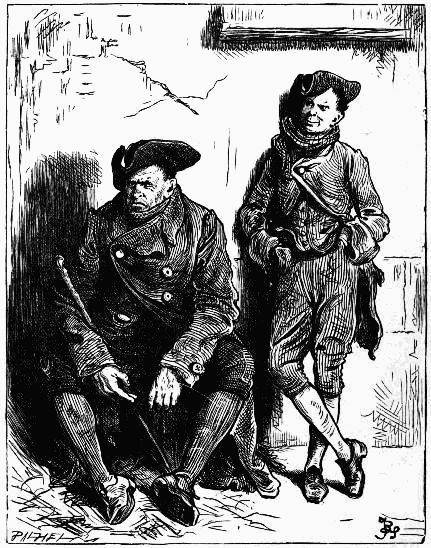

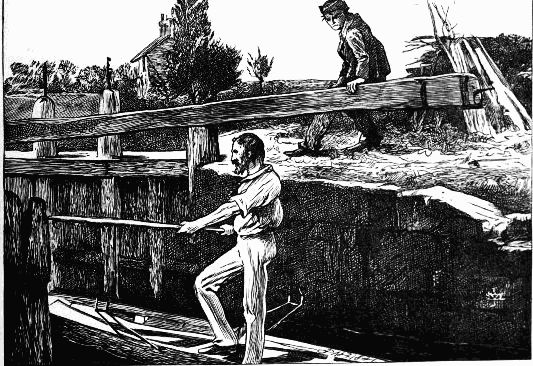

"Just send somebody out to relieve my mate, will you, young man?"—Chap. xxxi.

"Just send somebody out to relieve my mate, will you, young man?"—Chap. xxxi.

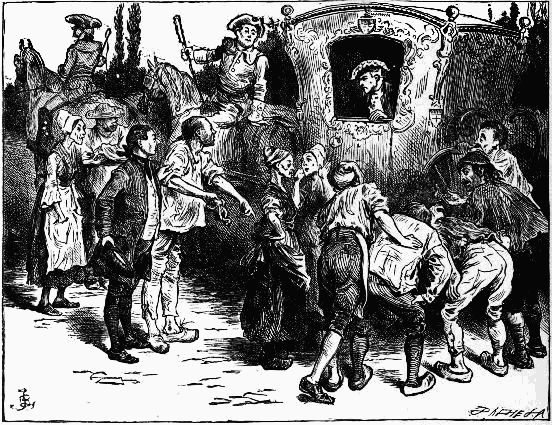

Looking round, he saw that it was a post-chaise, driven at great speed—Chap. xxxiv.

Looking round, he saw that it was a post-chaise, driven at great speed—Chap. xxxiv.

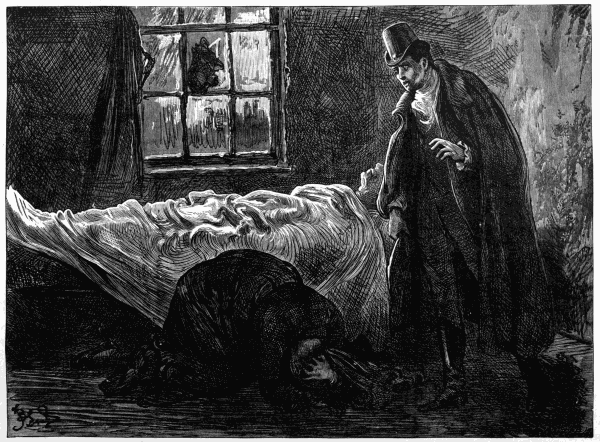

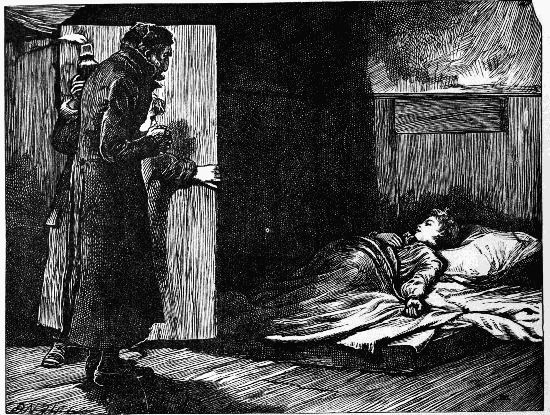

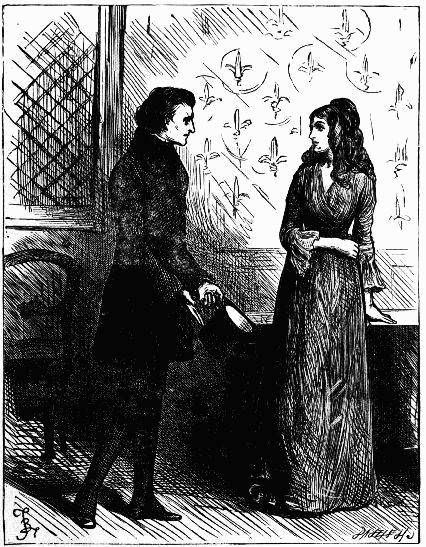

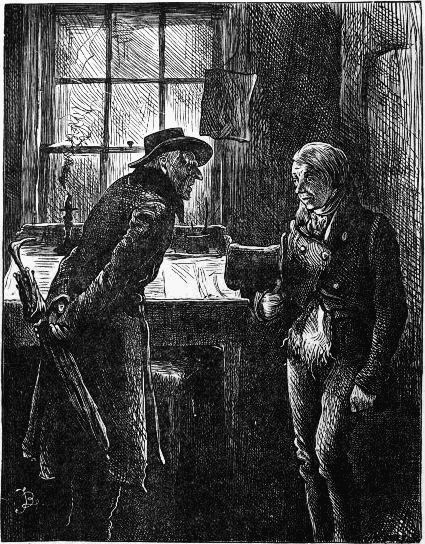

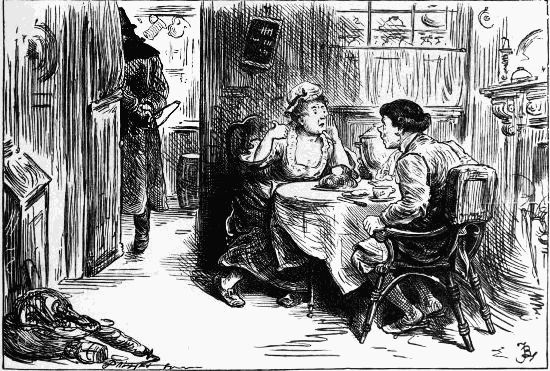

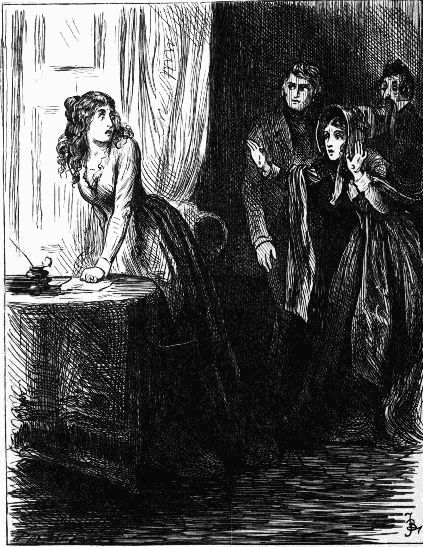

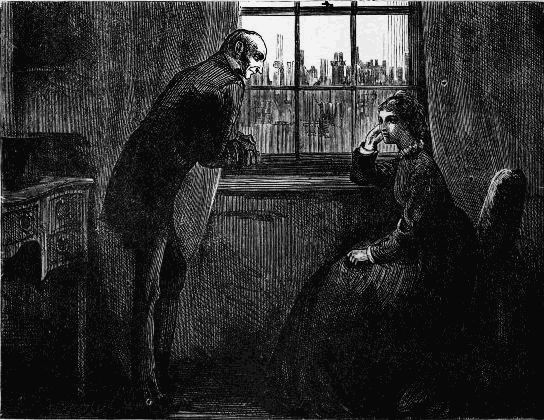

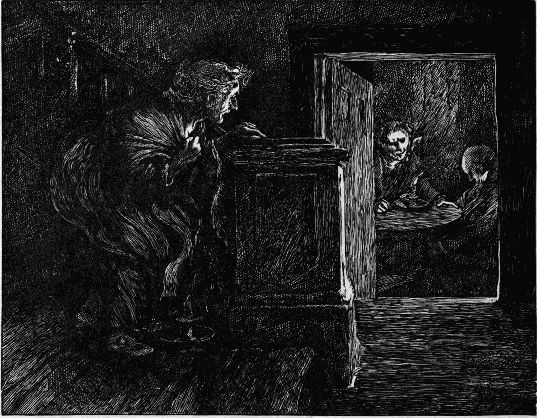

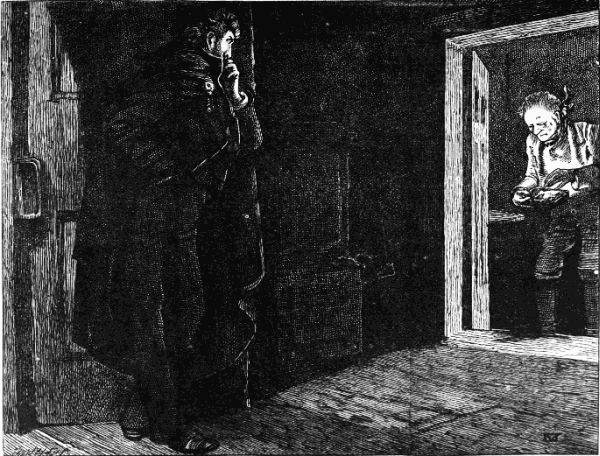

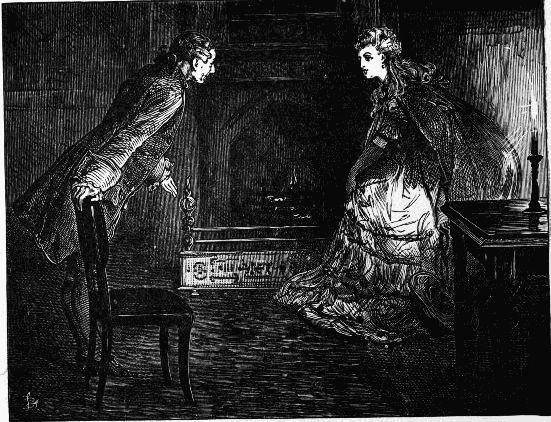

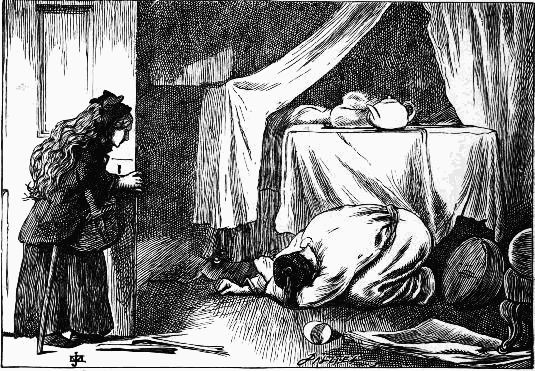

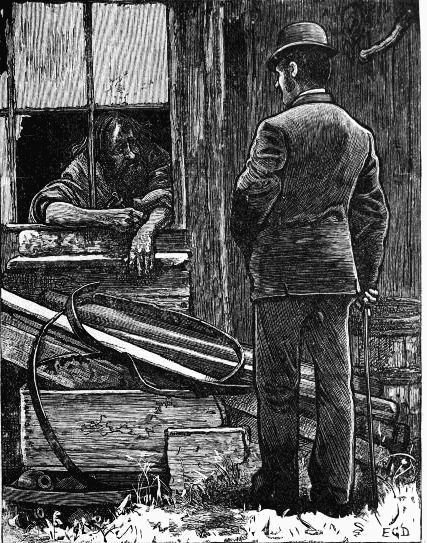

"Were you looking for me," he said, "when you peered in at the window?"—Chap. xxxvii.

"Were you looking for me," he said, "when you peered in at the window?"—Chap. xxxvii.

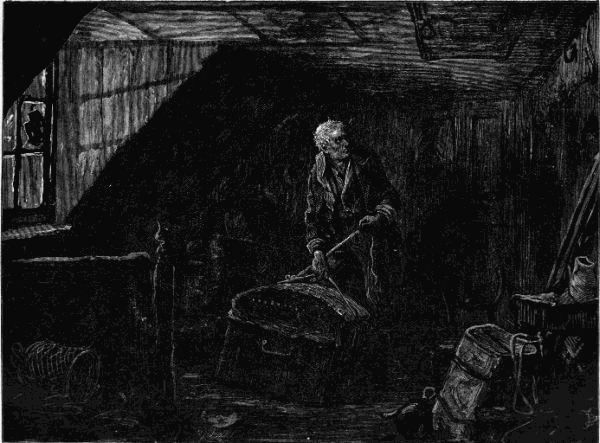

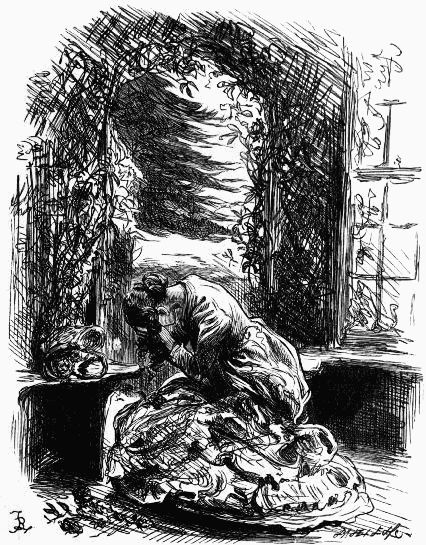

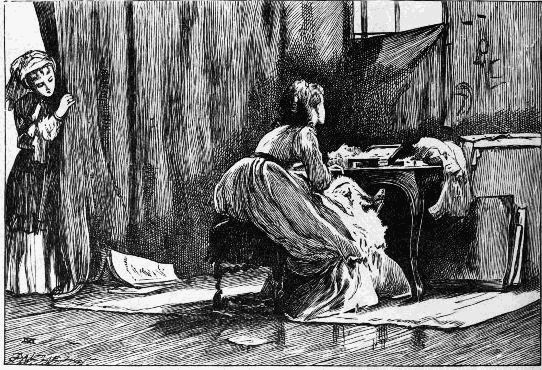

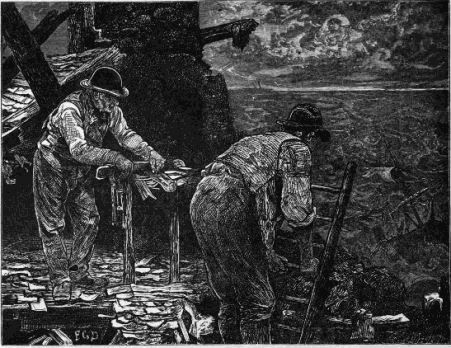

The evidence destroyed—Chap. xxxviii.

The evidence destroyed—Chap. xxxviii.

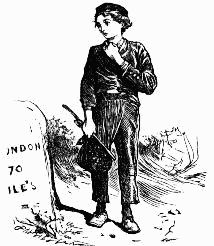

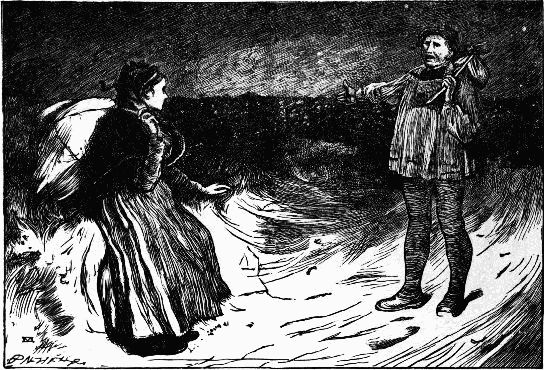

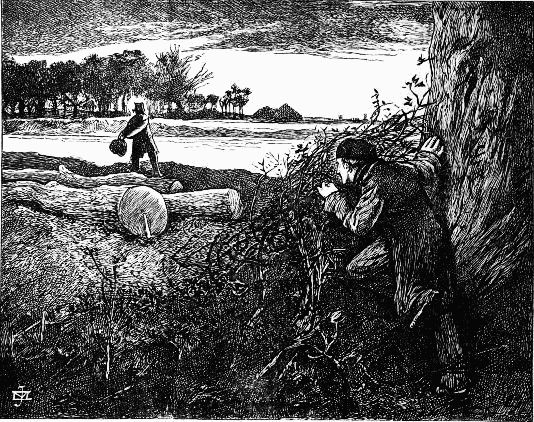

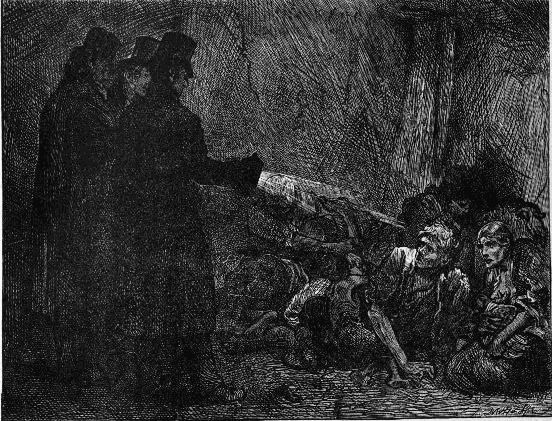

"Look there! Those are the lights of London"—Chap. xlii.

"Look there! Those are the lights of London"—Chap. xlii.

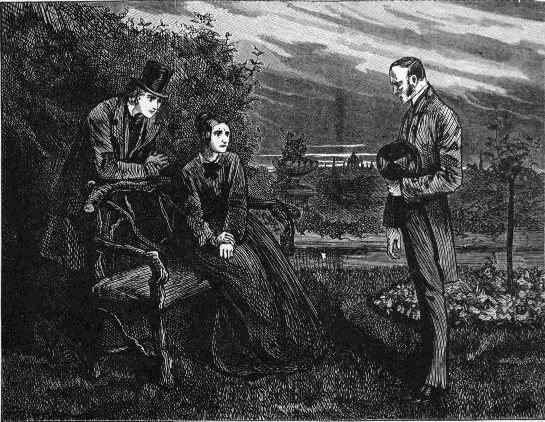

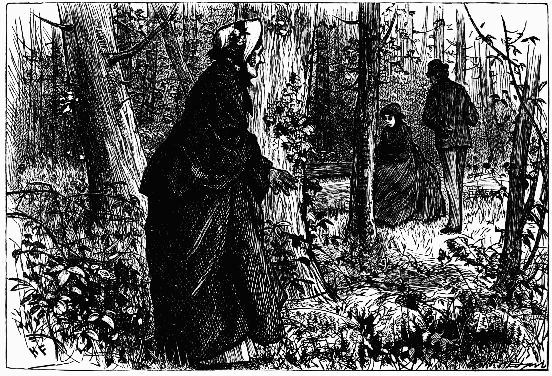

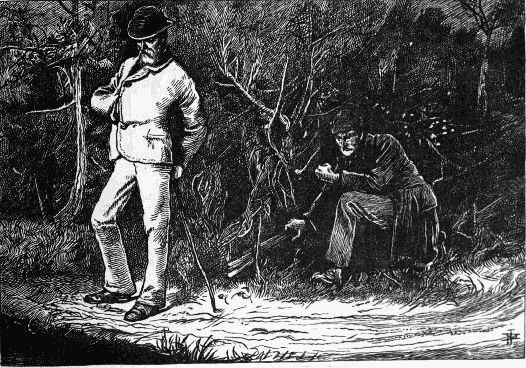

When she was about the same distance in advance as she had been before, he slipped quietly down,

and followed her again—Chap. xlvi.

When she was about the same distance in advance as she had been before, he slipped quietly down,

and followed her again—Chap. xlvi.

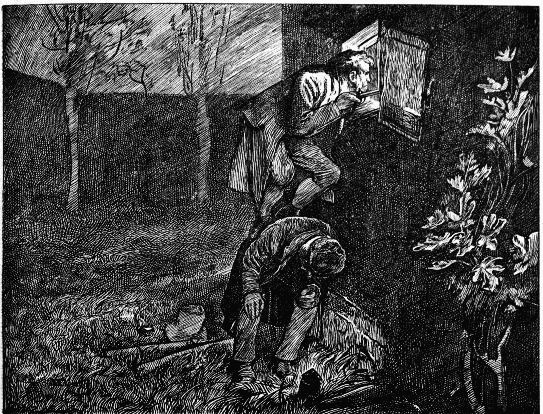

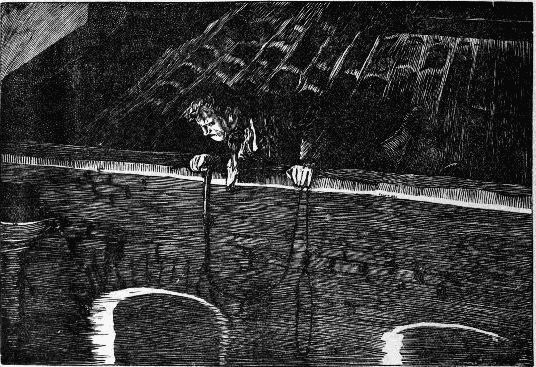

And creeping over the tiles, looked over the low parapet—Chap. l.

And creeping over the tiles, looked over the low parapet—Chap. l.

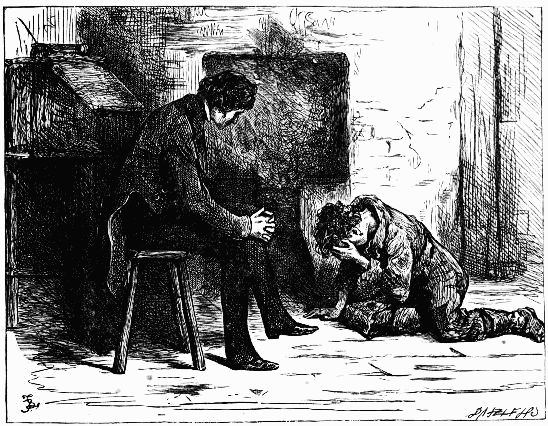

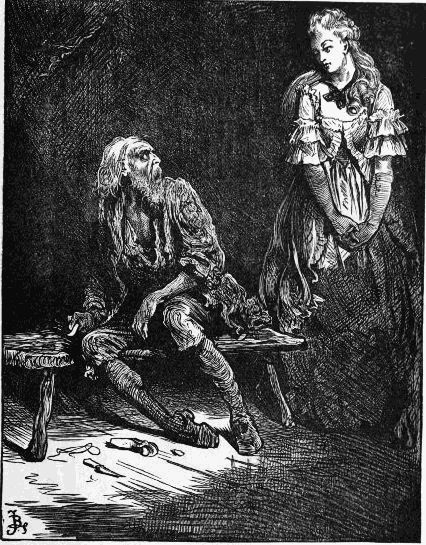

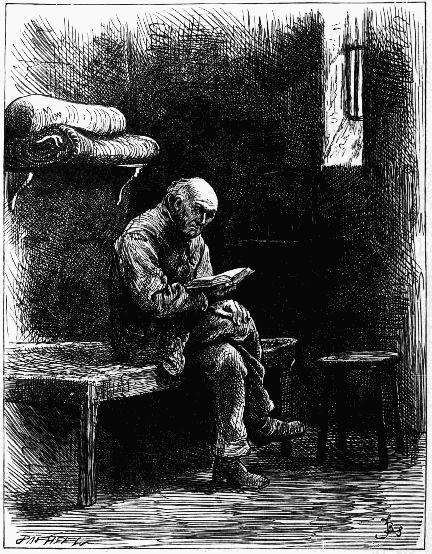

He sat down on the stone bench opposite the door—Chap. lvi.

He sat down on the stone bench opposite the door—Chap. lvi.

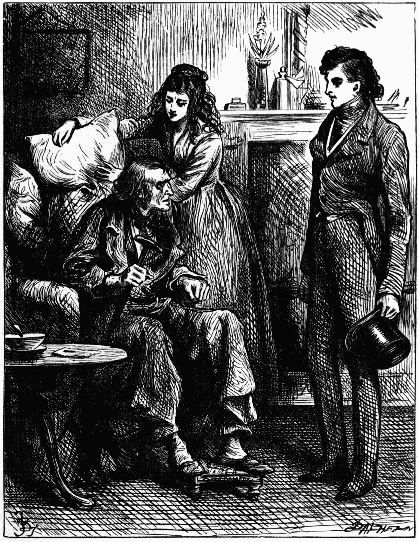

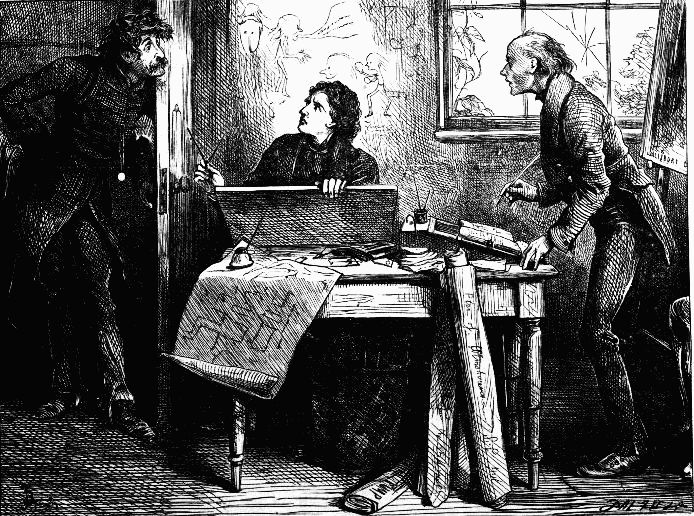

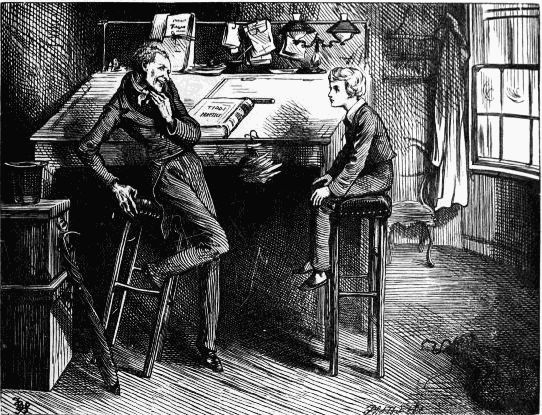

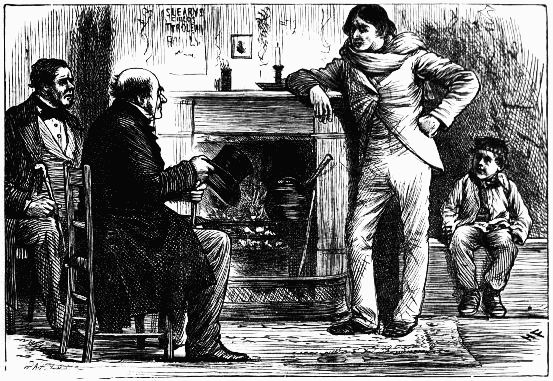

The Uncle and Nephew looked at each other for some seconds without speaking—Chap. iii.

The Uncle and Nephew looked at each other for some seconds without speaking—Chap. iii.

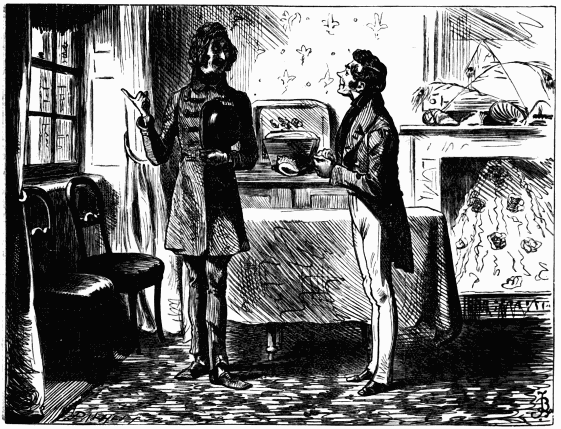

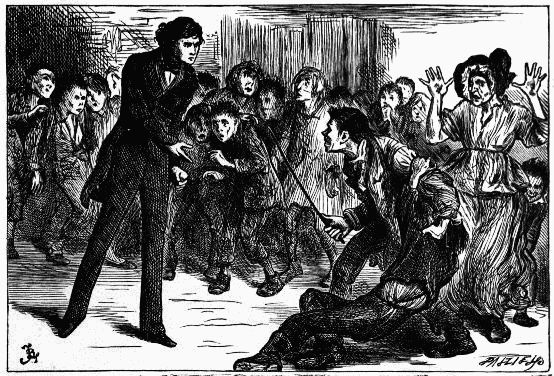

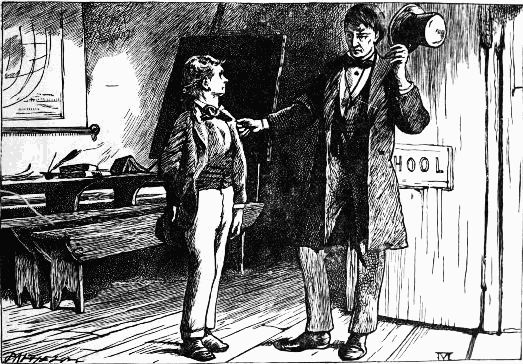

The schoolmaster and his companion looked steadily at each other for a few seconds, and then exchanged a very meaning smile—Chap. iv.

The schoolmaster and his companion looked steadily at each other for a few seconds, and then exchanged a very meaning smile—Chap. iv.

"Snubs and Romans are plentiful enough, and there are flats of all sorts

and sizes when there's a meeting at Exeter Hall"—Chap. v.

"Snubs and Romans are plentiful enough, and there are flats of all sorts

and sizes when there's a meeting at Exeter Hall"—Chap. v.

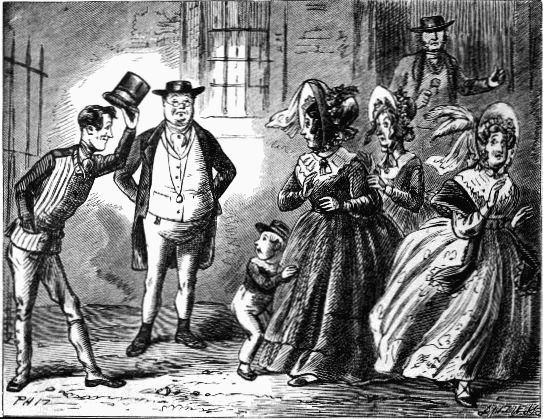

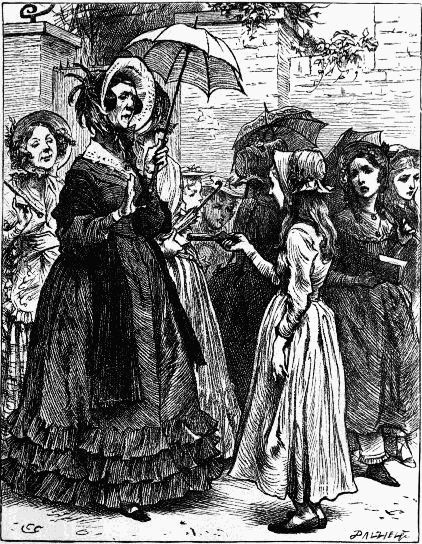

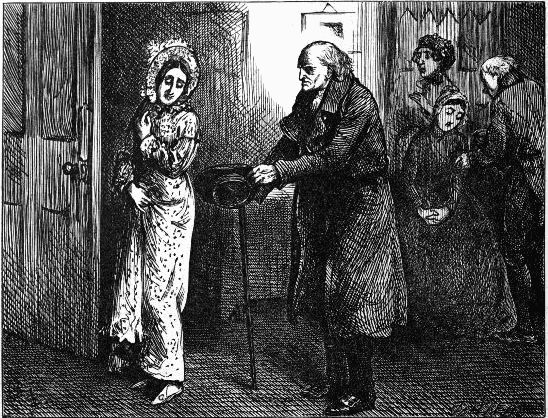

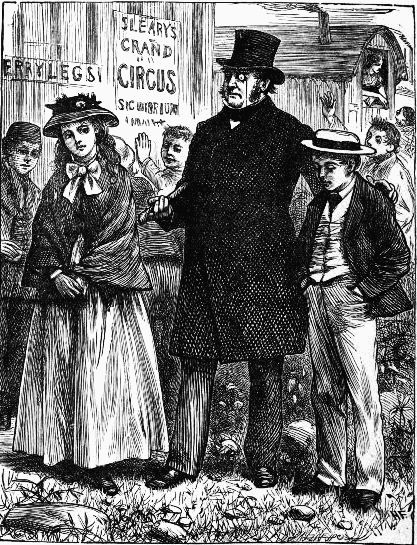

"Very glad to make your acquaintance, Miss," said Squeers, raising his hat an

inch or two—Chap. v.

"Very glad to make your acquaintance, Miss," said Squeers, raising his hat an

inch or two—Chap. v.

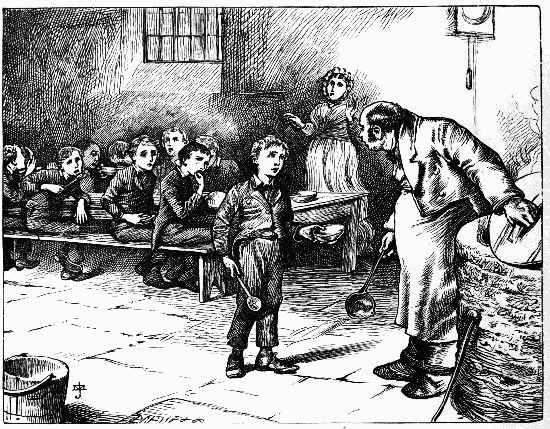

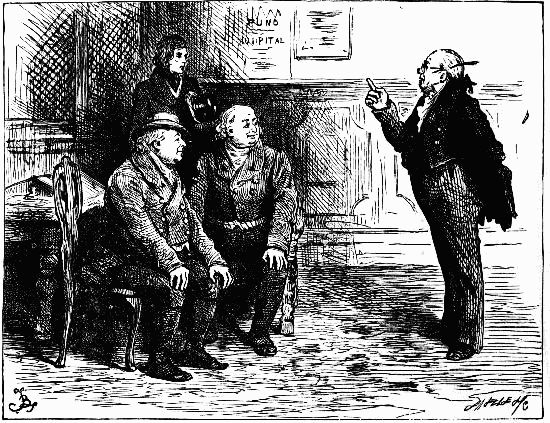

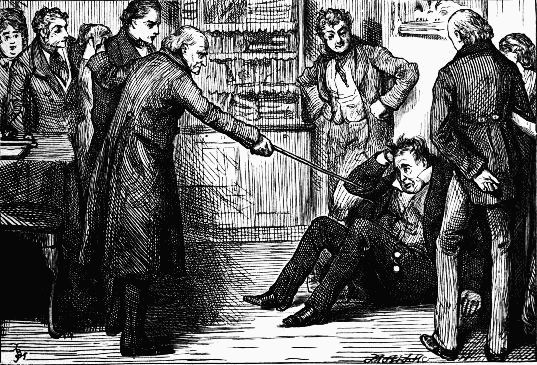

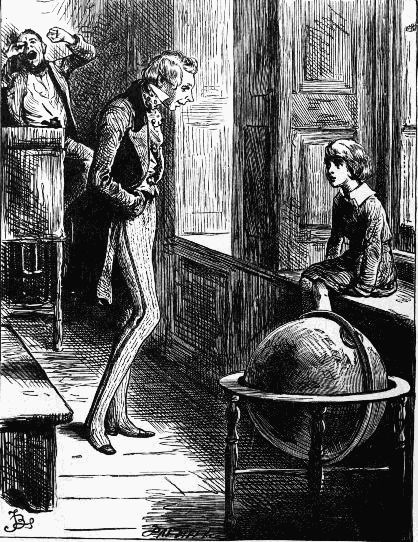

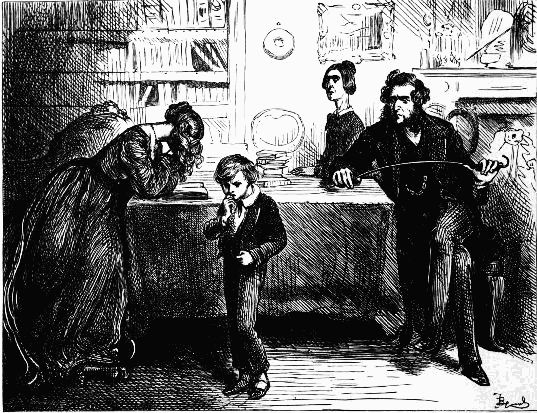

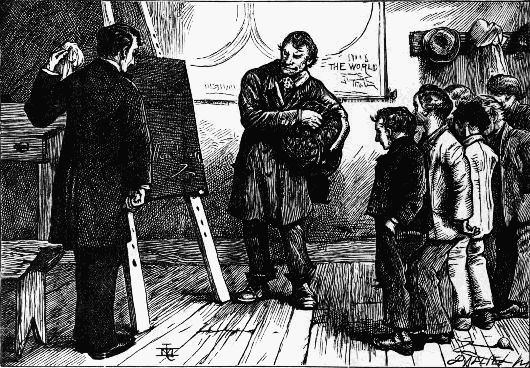

The first class English spelling and philosophy—Chap. viii.

The first class English spelling and philosophy—Chap. viii.

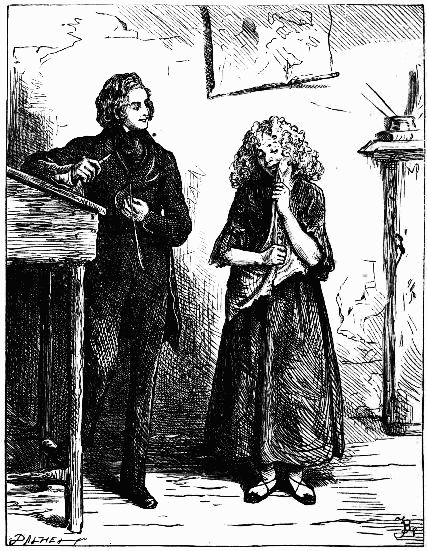

Kate walked sadly back to their lodgings in the Strand—Chap. x.

Kate walked sadly back to their lodgings in the Strand—Chap. x.

"Oh! as soft as possible, if you please"—Chap. ix.

"Oh! as soft as possible, if you please"—Chap. ix.

"I can—not help it, and it don't signify," sobbed Mrs. Kenwigs. "Oh! they're too beautiful to live,

much too beautiful!"—Chap. xiv.

"I can—not help it, and it don't signify," sobbed Mrs. Kenwigs. "Oh! they're too beautiful to live,

much too beautiful!"—Chap. xiv.

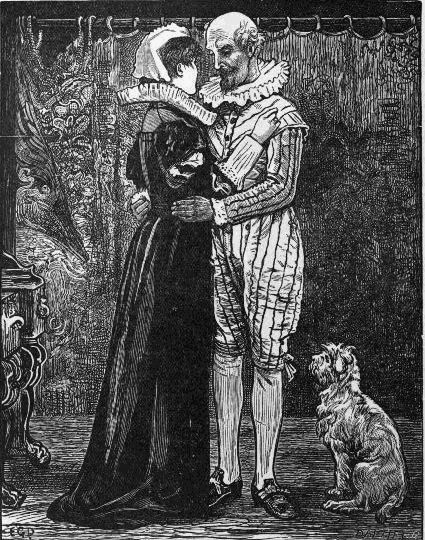

"I don't forget you, my soul, and never shall, and never can," said Mantalini, kissing his wife's hand

and grimacing aside to Miss Nickleby, who turned away—Chap. xvii.

"I don't forget you, my soul, and never shall, and never can," said Mantalini, kissing his wife's hand

and grimacing aside to Miss Nickleby, who turned away—Chap. xvii.

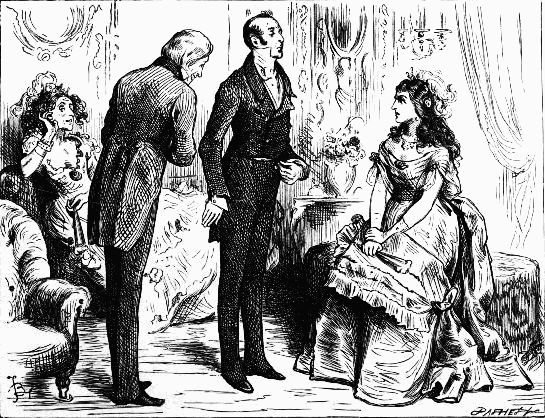

"I am afraid you have been giving her some of your wicked looks, my lord," said the intended—Chap. xviii.

"I am afraid you have been giving her some of your wicked looks, my lord," said the intended—Chap. xviii.

The dressing-room door being hastily flung open, Mr. Mantalini was disclosed to view, with his shirt

collar symmetrically thrown back: putting a fine edge to a breakfast knife by means of his razor

strop—Chap. xxi.

The dressing-room door being hastily flung open, Mr. Mantalini was disclosed to view, with his shirt

collar symmetrically thrown back: putting a fine edge to a breakfast knife by means of his razor

strop—Chap. xxi.

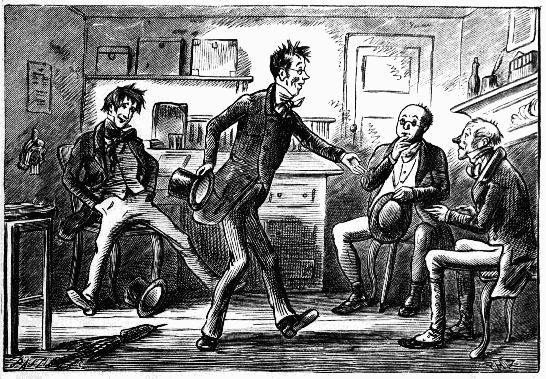

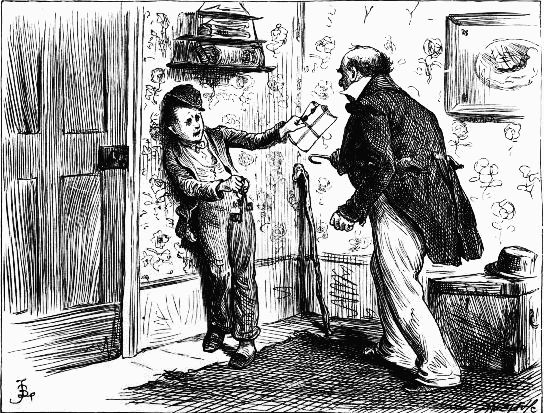

"You can just give him that ere card, and tell him if he wants to speak to me, and save trouble, here I am, that's all"—Chap. xxi.

"You can just give him that ere card, and tell him if he wants to speak to me, and save trouble, here I am, that's all"—Chap. xxi.

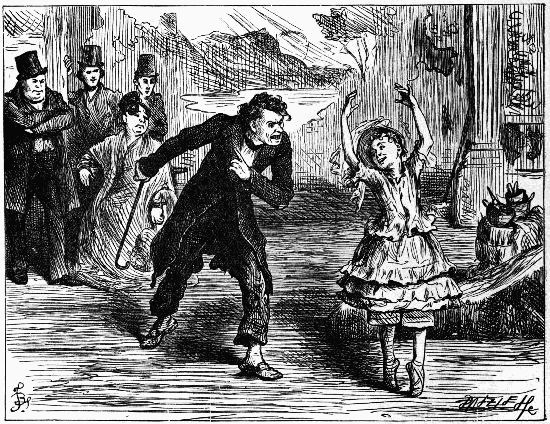

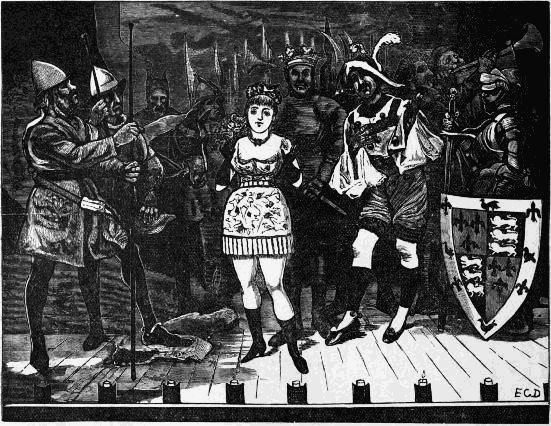

The Indian savage and the maiden—Chap. xxiii.

The Indian savage and the maiden—Chap. xxiii.

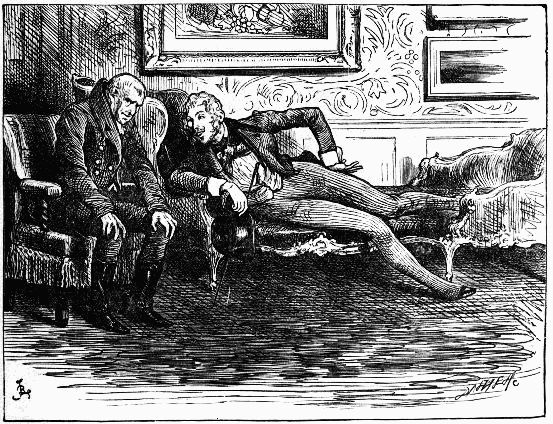

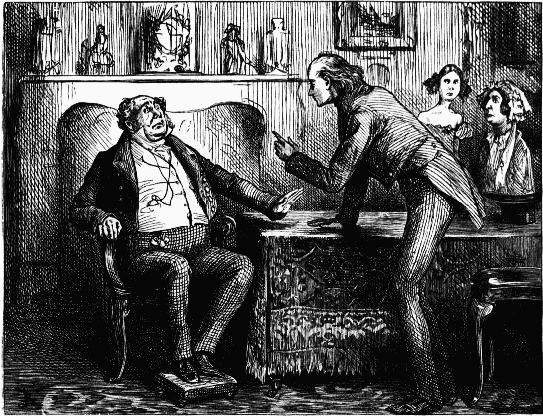

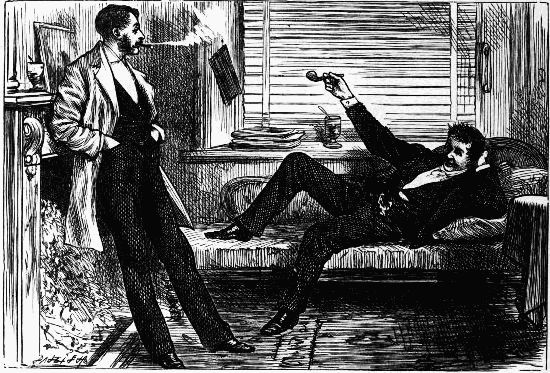

"Nickleby," said his client, throwing himself along the sofa on which he had been previously seated,

so as to bring his lips nearer to the old man's ear, "what a pretty creature your niece is!"—Chap. xxvi.

"Nickleby," said his client, throwing himself along the sofa on which he had been previously seated,

so as to bring his lips nearer to the old man's ear, "what a pretty creature your niece is!"—Chap. xxvi.

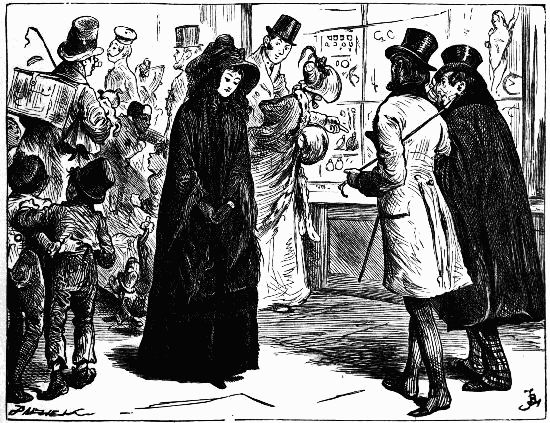

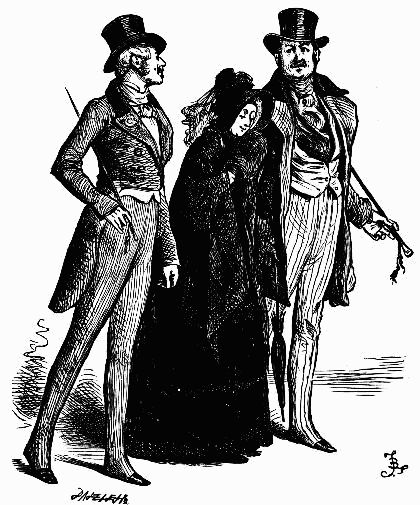

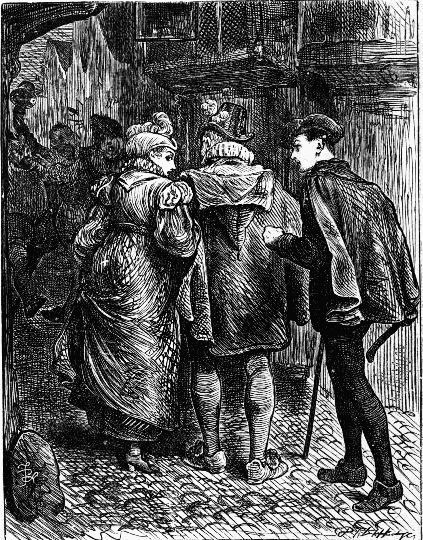

Sir Mulberry Hawk and his friend exchanged glances over the top of the

bonnet—Chap. xxvi.

Sir Mulberry Hawk and his friend exchanged glances over the top of the

bonnet—Chap. xxvi.

"I see how it is," said poor Noggs, drawing from his pocket what seemed to be

a very old duster, and wiping Kate's eyes with it as gently as if she were an

infant—Chap. xxviii.

"I see how it is," said poor Noggs, drawing from his pocket what seemed to be

a very old duster, and wiping Kate's eyes with it as gently as if she were an

infant—Chap. xxviii.

Mr. Snevellicci repeated the wink, and, drinking to Mrs. Lilyvick in dumb-show, actually blew her a

kiss—Chap. xxx.

Mr. Snevellicci repeated the wink, and, drinking to Mrs. Lilyvick in dumb-show, actually blew her a

kiss—Chap. xxx.

"Look at them tears, Sir!" said Squeers with a triumphant air, as master Wackford wiped his eyes with

the cuff of his jacket; "there's oiliness"—Chap. xxxiv.

"Look at them tears, Sir!" said Squeers with a triumphant air, as master Wackford wiped his eyes with

the cuff of his jacket; "there's oiliness"—Chap. xxxiv.

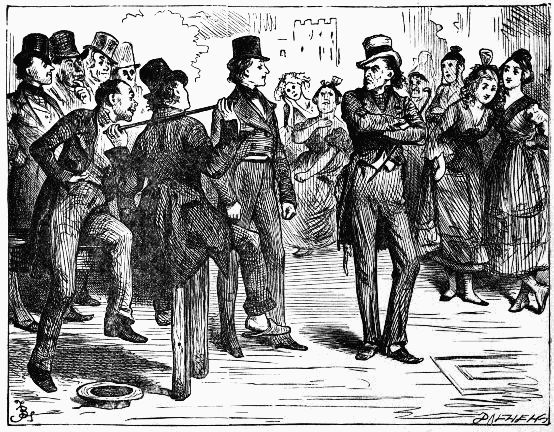

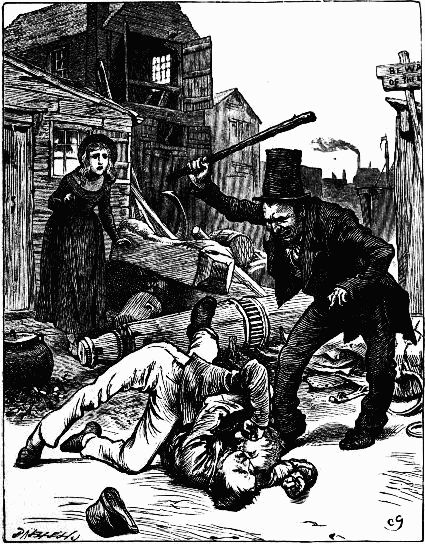

Sir Mulberry, shortening his whip, applied it furiously to the head and shoulders of Nicholas. It was broken in the struggle:

Nicholas gained the heavy handle, and with it laid open one side of his antagonist's face from the eye to the lip—Chap. xxxii.

Sir Mulberry, shortening his whip, applied it furiously to the head and shoulders of Nicholas. It was broken in the struggle:

Nicholas gained the heavy handle, and with it laid open one side of his antagonist's face from the eye to the lip—Chap. xxxii.

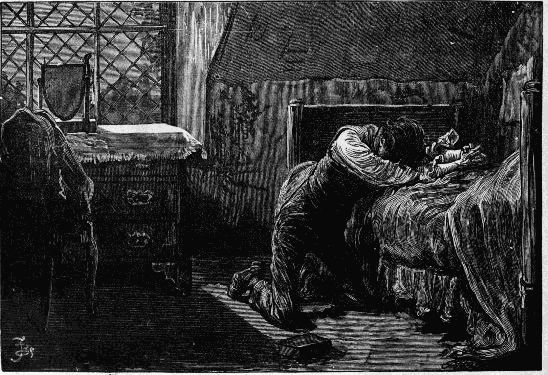

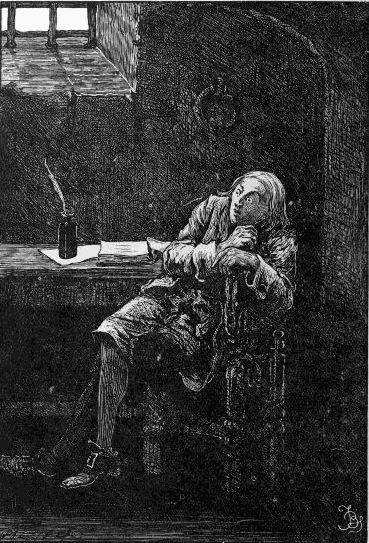

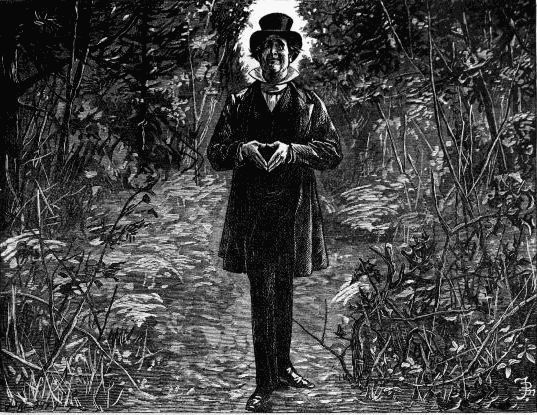

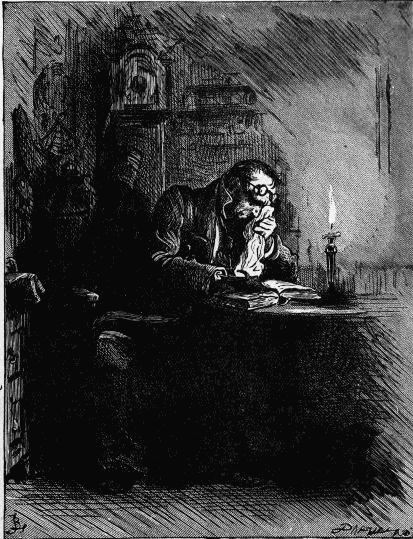

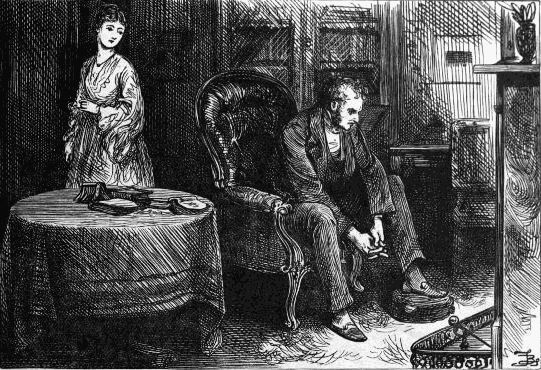

Night found him, at last, still harping on the same theme, and still pursuing

the same unprofitable reflections—Chap. xxxiv.

Night found him, at last, still harping on the same theme, and still pursuing

the same unprofitable reflections—Chap. xxxiv.

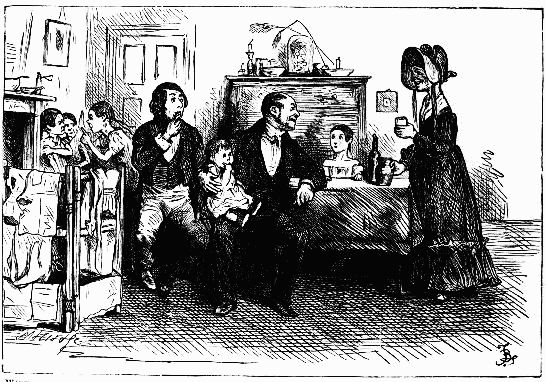

With this the doctor laughed; but he didn't laugh half as much as a married friend of Mrs.

Kenwigs's, who had just come in from the sick chamber—Chap. xxxvi.

With this the doctor laughed; but he didn't laugh half as much as a married friend of Mrs.

Kenwigs's, who had just come in from the sick chamber—Chap. xxxvi.

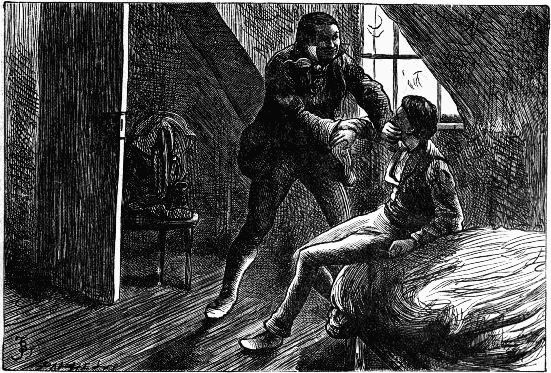

Darting in, covered Smike's mouth with his huge hand before he could utter a sound—Chap. xxxix.

Darting in, covered Smike's mouth with his huge hand before he could utter a sound—Chap. xxxix.

The meditative ogre—Chap. xl.

The meditative ogre—Chap. xl.

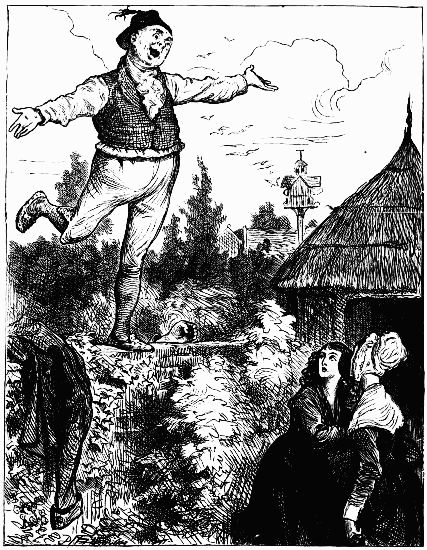

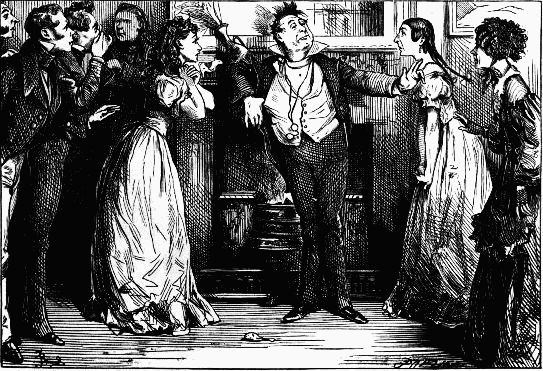

Concluded by standing on one leg, and repeating his favourite bellow with

increased vehemence—Chap. xli.

Concluded by standing on one leg, and repeating his favourite bellow with

increased vehemence—Chap. xli.

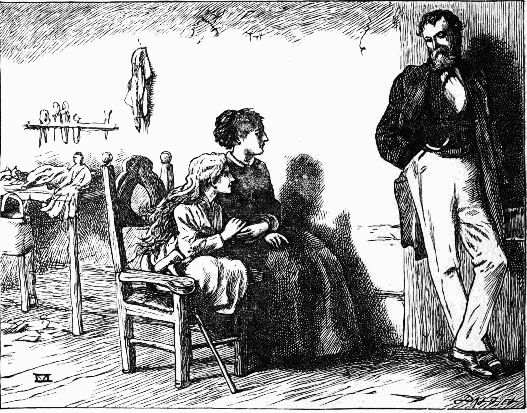

Fell upon his face in a passion of bitter grief—Chap. xliii.

Fell upon his face in a passion of bitter grief—Chap. xliii.

"I am a most miserable and wretched outcast, nearly sixty years old, and as

destitute and helpless as a child of six"—Chap. xliv.

"I am a most miserable and wretched outcast, nearly sixty years old, and as

destitute and helpless as a child of six"—Chap. xliv.

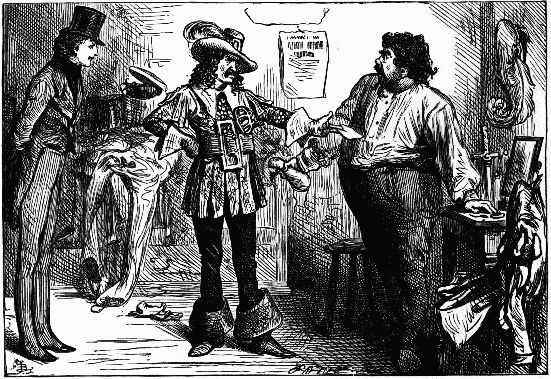

Was presently conducted by a robber, with a very large belt and buckle round his waist, and very

large leather gauntlets on his hands, into the presence of his former manager—Chap. xlviii.

Was presently conducted by a robber, with a very large belt and buckle round his waist, and very

large leather gauntlets on his hands, into the presence of his former manager—Chap. xlviii.

"No matter! do you think you bring your paltry money here as a favour or a

gift; or as a matter of business, and in return for value received"—Chap. xlvi.

"No matter! do you think you bring your paltry money here as a favour or a

gift; or as a matter of business, and in return for value received"—Chap. xlvi.

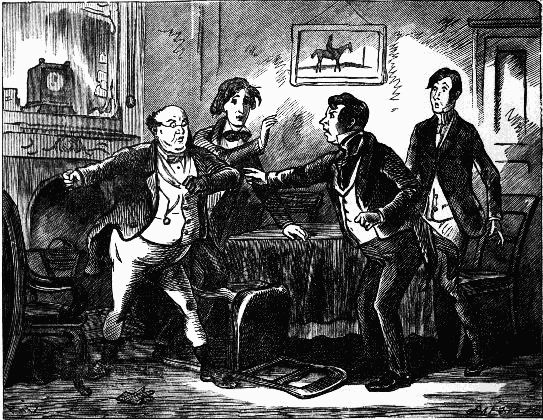

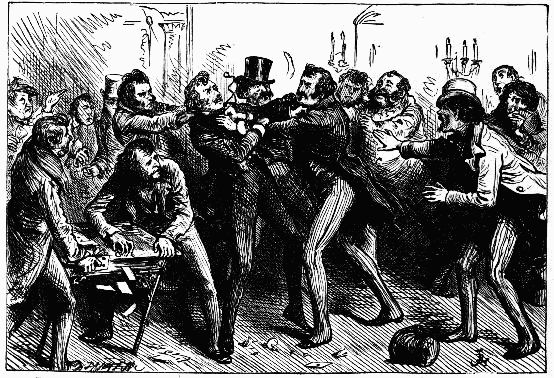

Two men, seizing each other by the throat, struggled into the middle of the room—Chap. l.

Two men, seizing each other by the throat, struggled into the middle of the room—Chap. l.

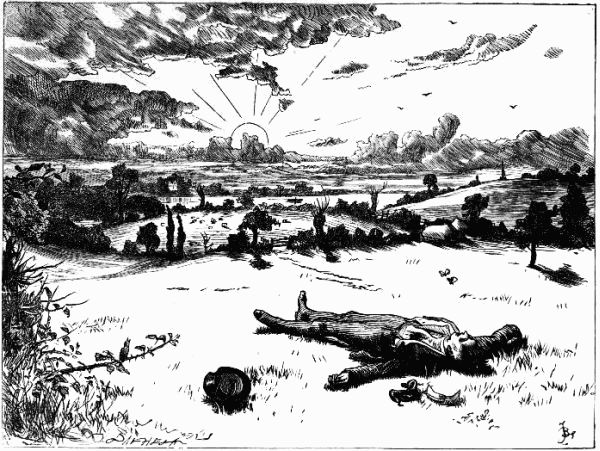

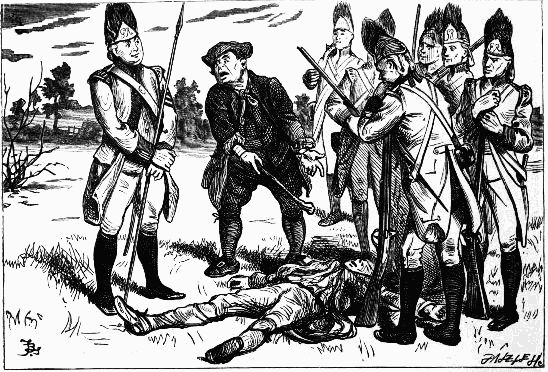

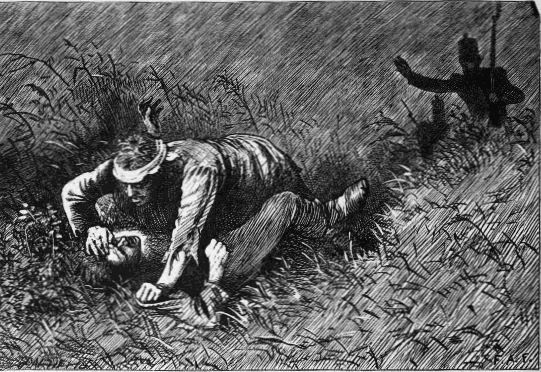

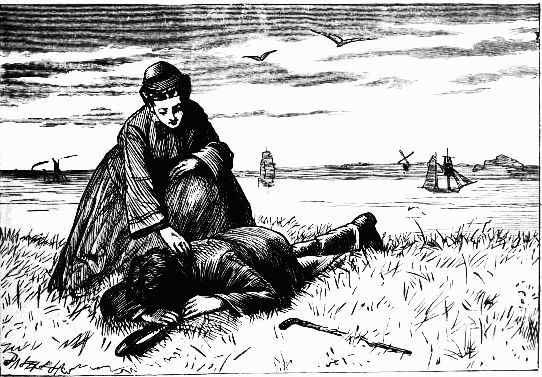

All the light and life of day came on; and amidst it all, and pressing down the grass whose every blade bore twenty tiny lives,

lay the dead man, with his stark and rigid face turned upwards to the sky—Chap. l.

All the light and life of day came on; and amidst it all, and pressing down the grass whose every blade bore twenty tiny lives,

lay the dead man, with his stark and rigid face turned upwards to the sky—Chap. l.

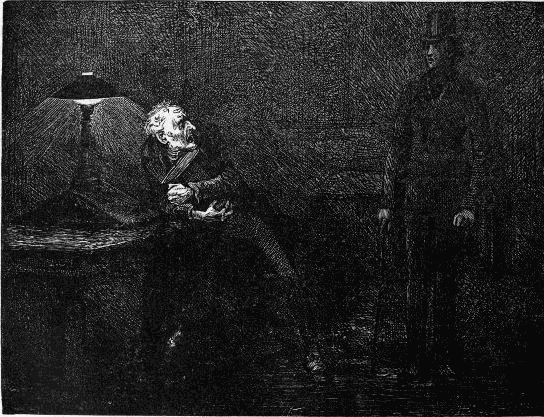

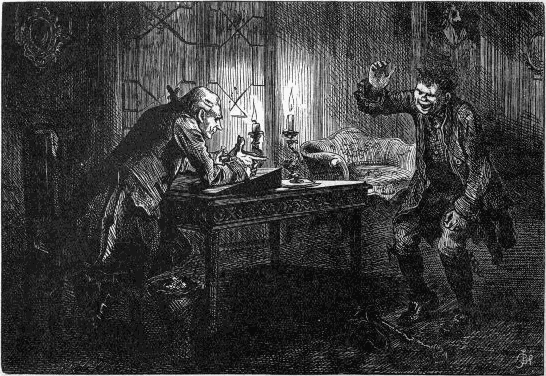

"Thieves! thieves!" shrieked the usurer, starting up and folding his book to his breast; "robbers!

murder!"—Chap. liii.

"Thieves! thieves!" shrieked the usurer, starting up and folding his book to his breast; "robbers!

murder!"—Chap. liii.

"I must beseech you to contemplate again the fearful course to which you have

been impelled"—Chap. liii.

"I must beseech you to contemplate again the fearful course to which you have

been impelled"—Chap. liii.

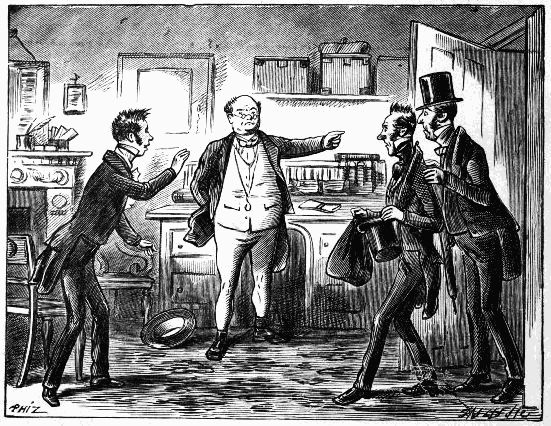

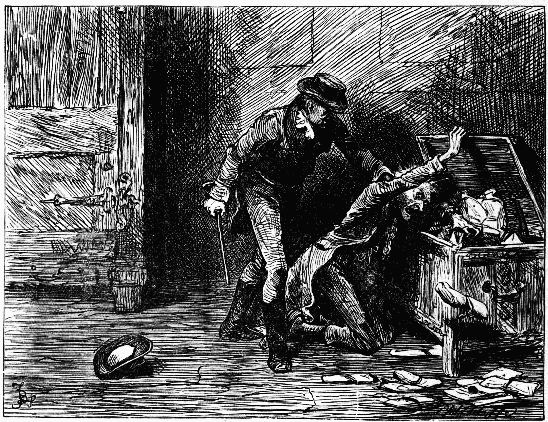

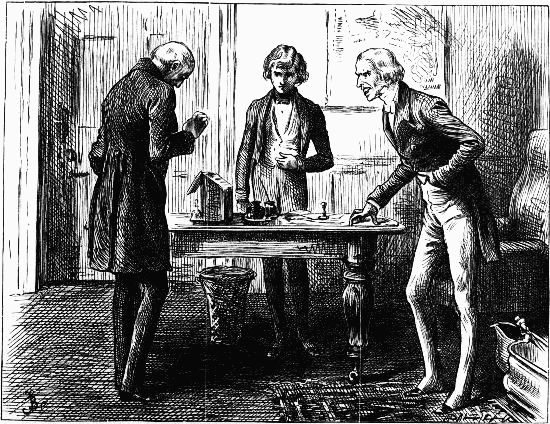

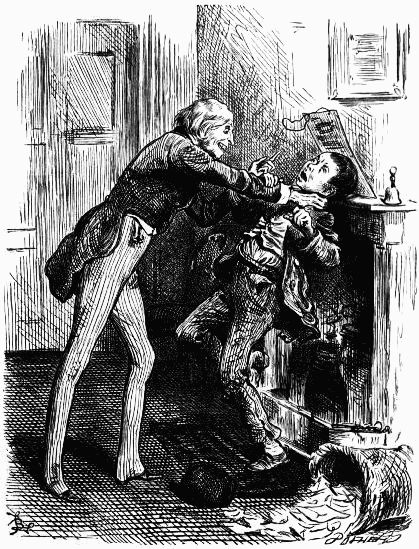

"There is something missing, you say," said Ralph, shaking him furiously by the collar. "What is it?"—Chap. lvi.

"There is something missing, you say," said Ralph, shaking him furiously by the collar. "What is it?"—Chap. lvi.

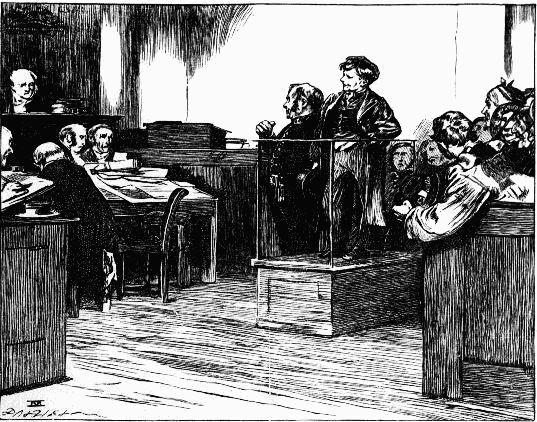

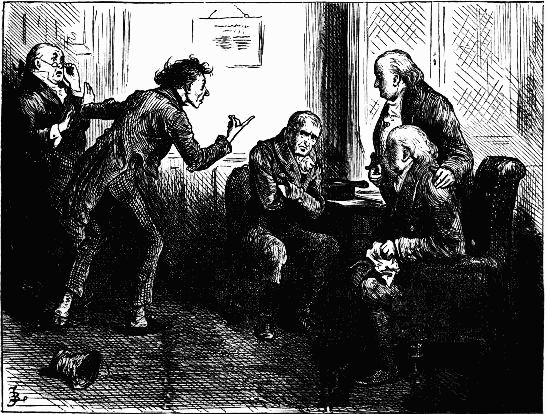

"Who tampered with a selfish father, urging him to sell his daughter to old Arthur Gride, and

tampered with Gride too, and did so in the little office, with a closet in the room"—Chap. lix.

"Who tampered with a selfish father, urging him to sell his daughter to old Arthur Gride, and

tampered with Gride too, and did so in the little office, with a closet in the room"—Chap. lix.

"Total, all up with Squeers!"—Chap. lx.

"Total, all up with Squeers!"—Chap. lx.

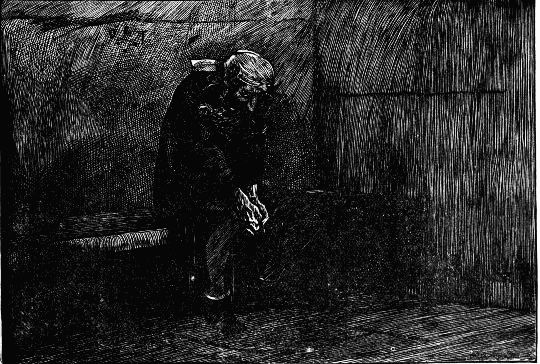

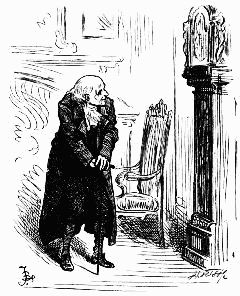

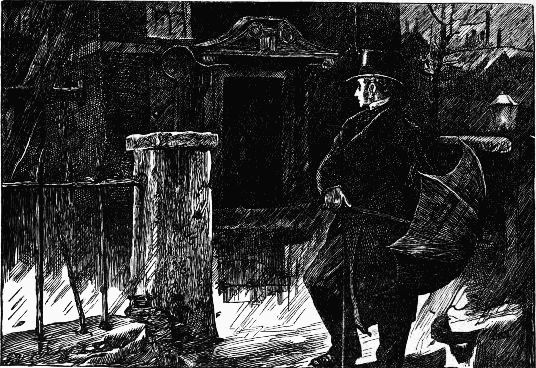

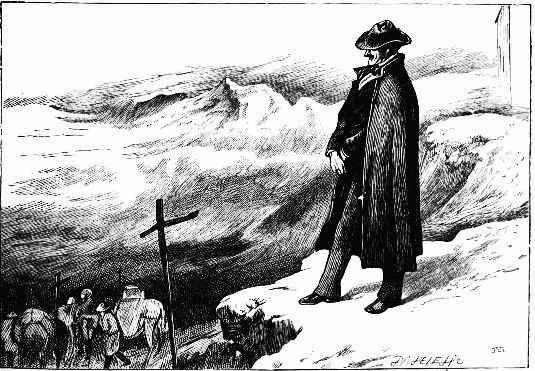

Ralph makes one last appointment—and keeps it—Chap. lxii.

Ralph makes one last appointment—and keeps it—Chap. lxii.

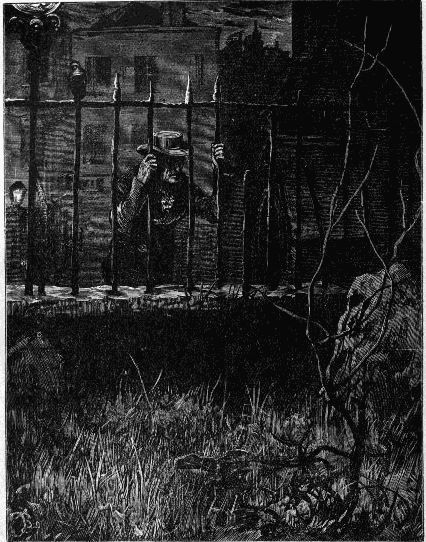

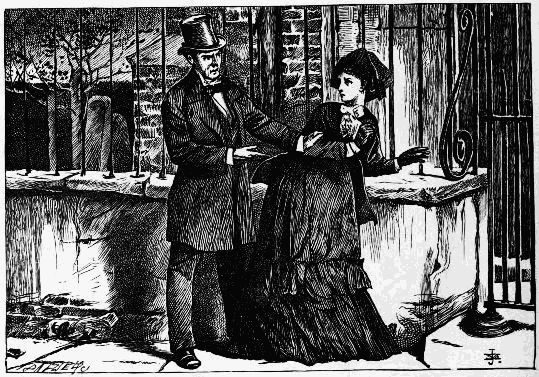

Clasping the iron railings with his hands, looked eagerly in, wondering which

might be his grave—Chap. lxii.

Clasping the iron railings with his hands, looked eagerly in, wondering which

might be his grave—Chap. lxii.

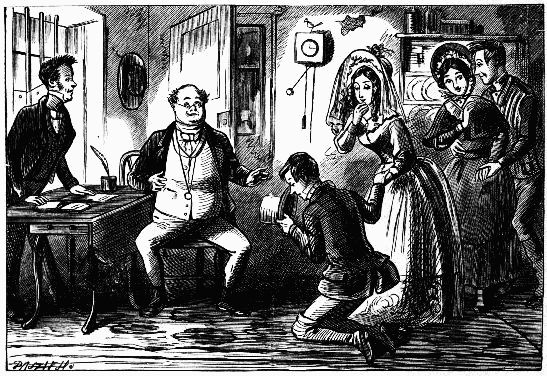

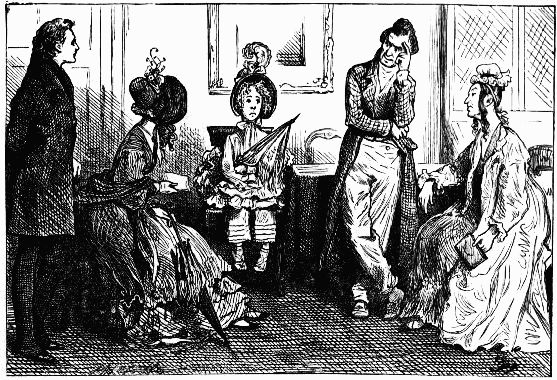

"Oh, Mr. Linkinwater, you're joking!" "No, no, I'm not. I'm not indeed," said Tim.

"I will, if you will. Do, my dear!"—Chap. lxiii.

"Oh, Mr. Linkinwater, you're joking!" "No, no, I'm not. I'm not indeed," said Tim.

"I will, if you will. Do, my dear!"—Chap. lxiii.

The little people could do nothing without dear Newman Noggs—Chap. lxv.

The little people could do nothing without dear Newman Noggs—Chap. lxv.

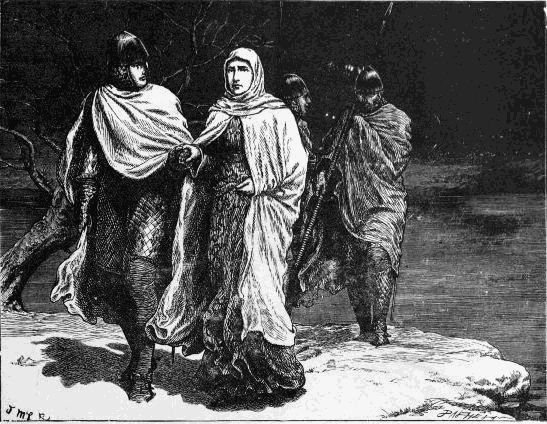

At such times, or when the shouts of straggling brawlers met her ear, the

Bowyer's daughter would look timidly back at Hugh, beseeching him to draw

nearer.—Master Humphrey's Clock, chap. i.

At such times, or when the shouts of straggling brawlers met her ear, the

Bowyer's daughter would look timidly back at Hugh, beseeching him to draw

nearer.—Master Humphrey's Clock, chap. i.

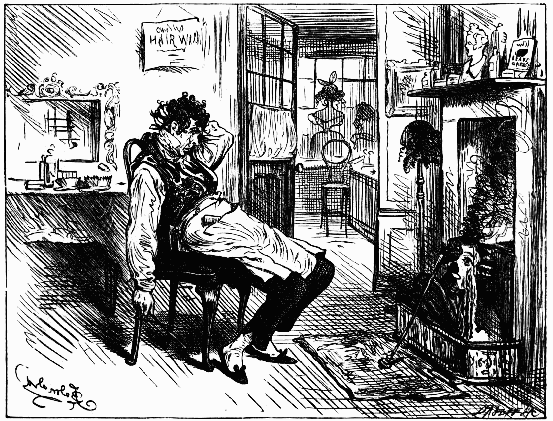

"Vith these vords he rushes into the shop, breaks the dummy's nose with a blow of his curlin'-irons,

melts him down at the parlour fire, and never smiles afterwards."—Master Humphrey's Clock, chap. v.

"Vith these vords he rushes into the shop, breaks the dummy's nose with a blow of his curlin'-irons,

melts him down at the parlour fire, and never smiles afterwards."—Master Humphrey's Clock, chap. v.

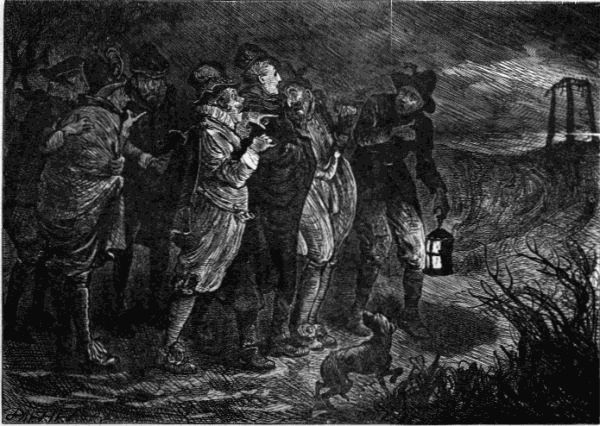

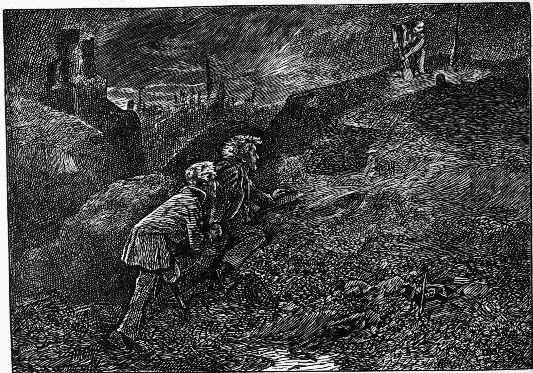

At last they made a halt at the opening of a lonely, desolate space, and, pointing to a black object at some distance, asked

Will if he saw that yonder.—Master Humphrey's Clock, chap. iii.

At last they made a halt at the opening of a lonely, desolate space, and, pointing to a black object at some distance, asked

Will if he saw that yonder.—Master Humphrey's Clock, chap. iii.

"With a look of scorn, she put into my hand a bit of paper, and took another

partner. On the paper was pencilled, 'Heavens! Can I write the word? Is my

husband a cow?'"—Holiday Romance, Part i.

"With a look of scorn, she put into my hand a bit of paper, and took another

partner. On the paper was pencilled, 'Heavens! Can I write the word? Is my

husband a cow?'"—Holiday Romance, Part i.

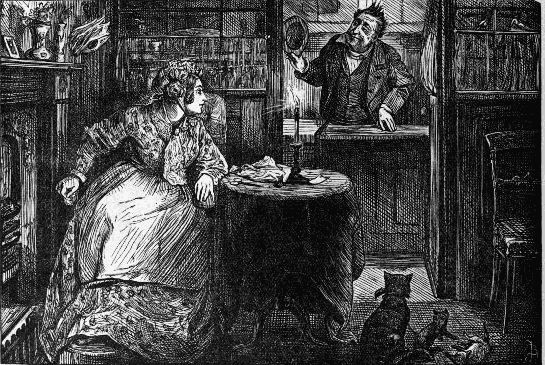

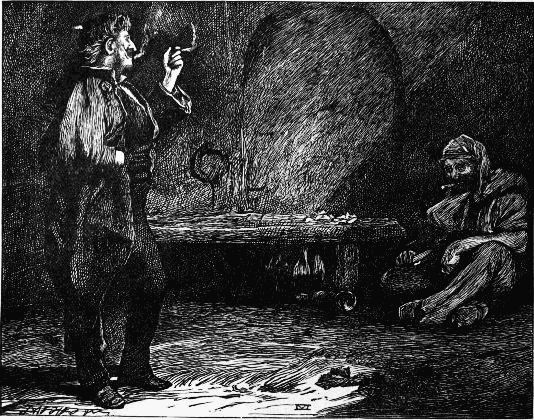

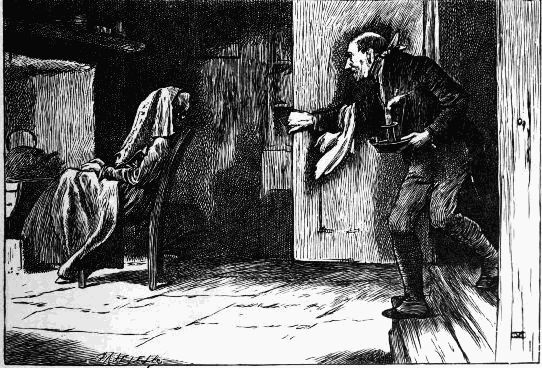

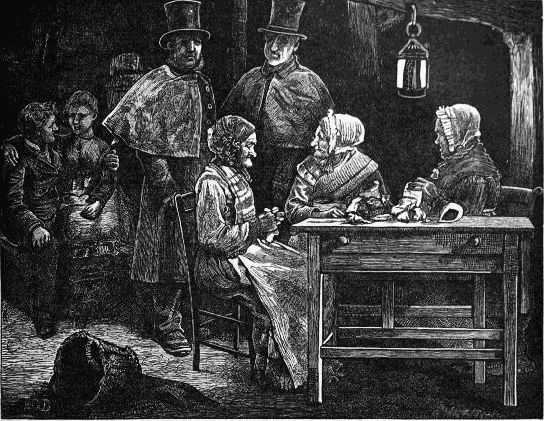

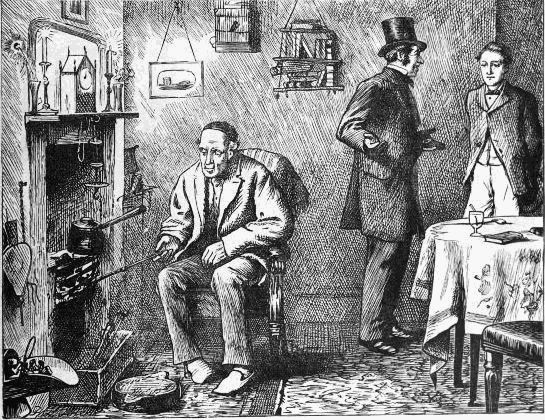

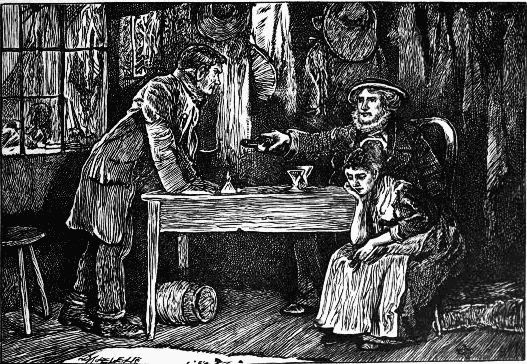

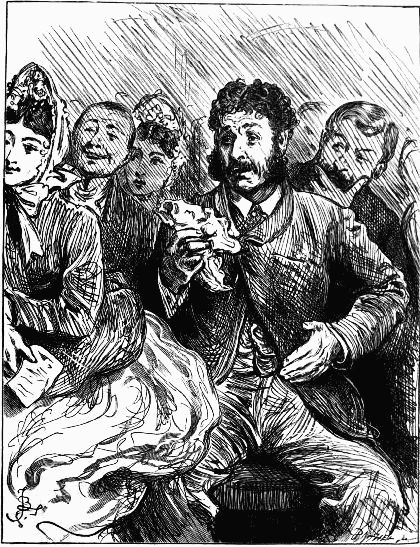

"What is the matter?" asked Brother Haukyard.

"Ay! what is the matter?" asked Brother Gimblet.—George Silverman's Explanation, chap. vi.

"What is the matter?" asked Brother Haukyard.

"Ay! what is the matter?" asked Brother Gimblet.—George Silverman's Explanation, chap. vi.

"You shall see me once again in the body, when you are tried for your life. You shall see me once

again in the spirit, when the cord is round your neck and the crowd are crying against you."—Hunted

Down, chap. v.

"You shall see me once again in the body, when you are tried for your life. You shall see me once

again in the spirit, when the cord is round your neck and the crowd are crying against you."—Hunted

Down, chap. v.

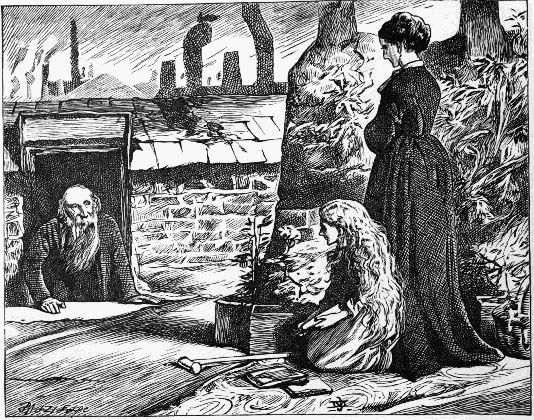

The door being opened, the child addressed him as her grandfather—Chap. i.

The door being opened, the child addressed him as her grandfather—Chap. i.

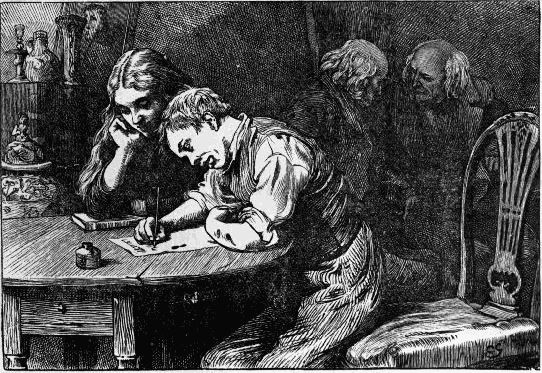

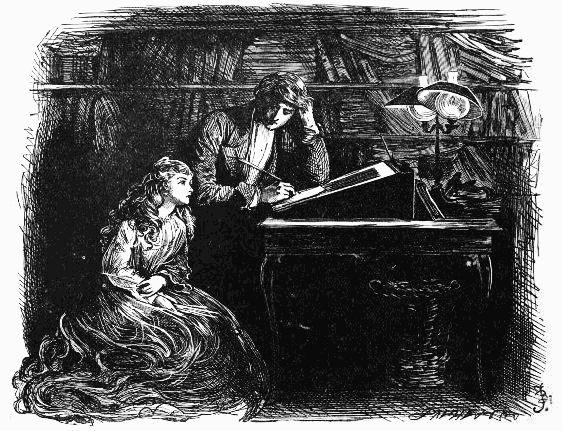

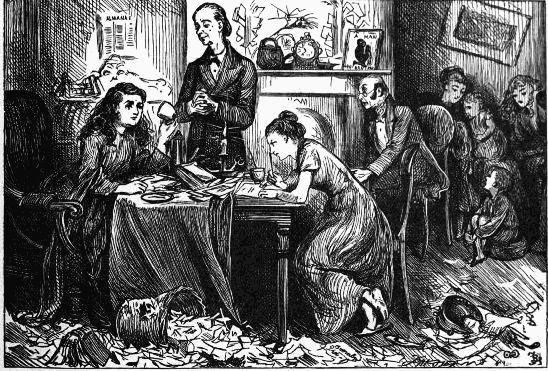

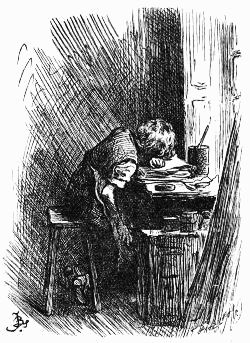

When he did sit down, he tucked up his sleeves and squared his elbows and put his face close to the

copy-book—Chap. iii.

When he did sit down, he tucked up his sleeves and squared his elbows and put his face close to the

copy-book—Chap. iii.

He soon cast his eyes upon a chair, into which he skipped with uncommon agility, and, perching himself

on the back with his feet upon the seat, was thus enabled to look on—Chap. ix.

He soon cast his eyes upon a chair, into which he skipped with uncommon agility, and, perching himself

on the back with his feet upon the seat, was thus enabled to look on—Chap. ix.

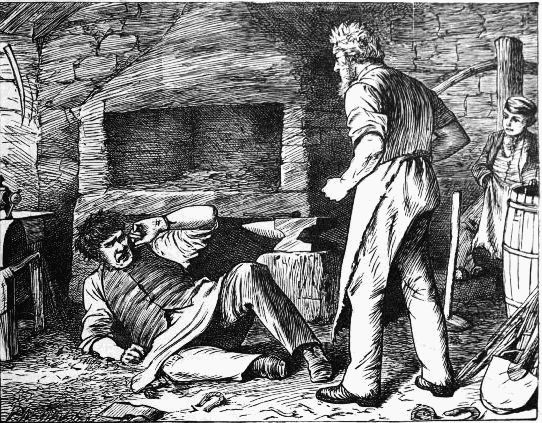

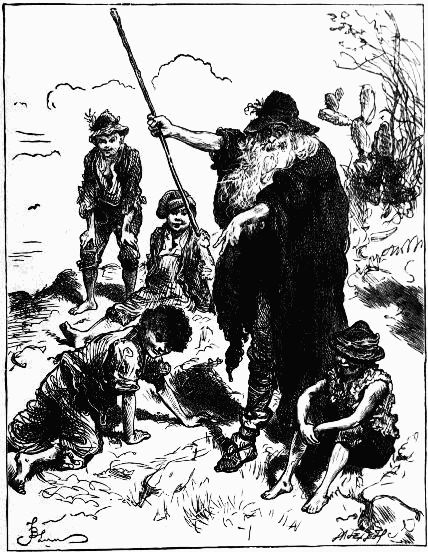

"I'll beat you to pulp, you dogs"—Chap. vi.

"I'll beat you to pulp, you dogs"—Chap. vi.

Not to be behindhand in the bustle, Mr. Quilp went to work with surprising vigour—Chap. xiii.

Not to be behindhand in the bustle, Mr. Quilp went to work with surprising vigour—Chap. xiii.

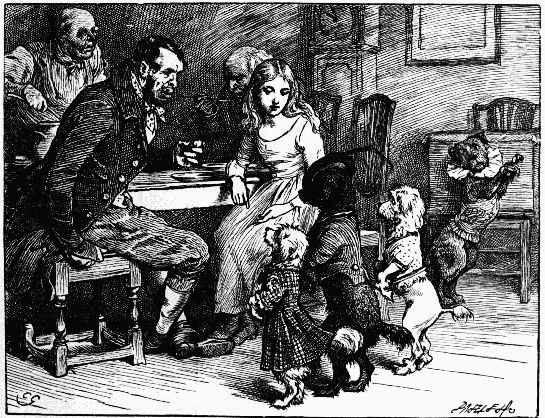

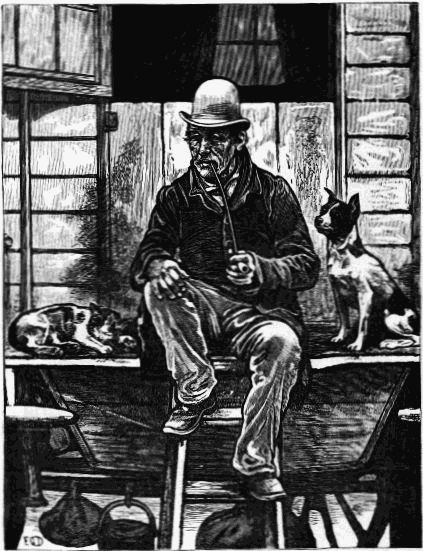

"Now, gentlemen," said Jerry, looking at them attentively, "the dog whose name's called, eats"—Chap. xviii.

"Now, gentlemen," said Jerry, looking at them attentively, "the dog whose name's called, eats"—Chap. xviii.

A small white-headed boy with a sunburnt face appeared at the door while he was speaking, and

stopping there to make a rustic bow, came in—Chap. xxv.

A small white-headed boy with a sunburnt face appeared at the door while he was speaking, and

stopping there to make a rustic bow, came in—Chap. xxv.

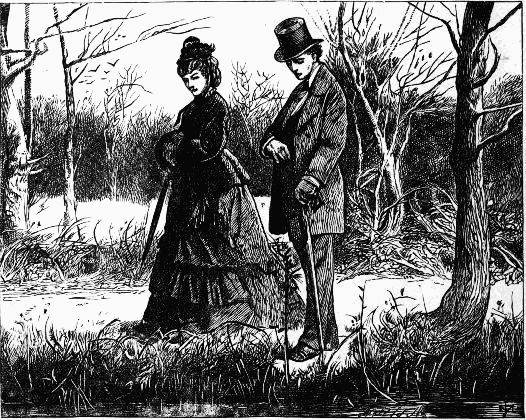

And then they went on arm-in-arm, very lovingly together—Chap. xxiii.

And then they went on arm-in-arm, very lovingly together—Chap. xxiii.

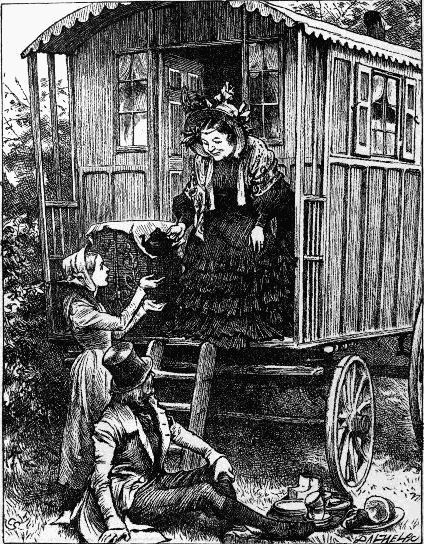

She handed down to them the tea-tray, the bread and butter, the knuckle of

ham, and, in short, everything of which she had partaken herself—Chap. xxvi.

She handed down to them the tea-tray, the bread and butter, the knuckle of

ham, and, in short, everything of which she had partaken herself—Chap. xxvi.

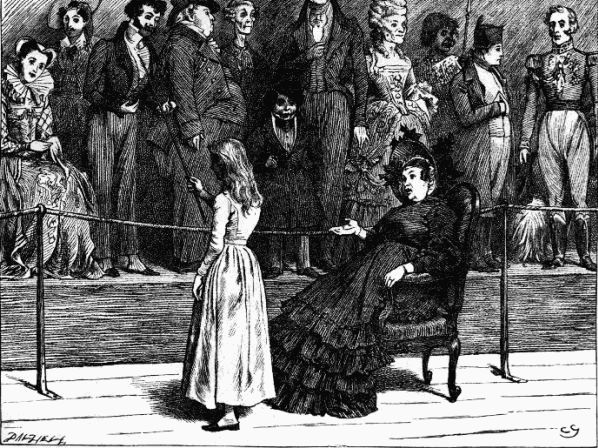

"That, ladies and gentlemen," said Mrs. Jarley, "is Jasper Packlemerton of atrocious memory"—Chap. xxviii.

"That, ladies and gentlemen," said Mrs. Jarley, "is Jasper Packlemerton of atrocious memory"—Chap. xxviii.

In some of these flourishes it went close to Miss Sally's head—Chap. xxxiii.

In some of these flourishes it went close to Miss Sally's head—Chap. xxxiii.

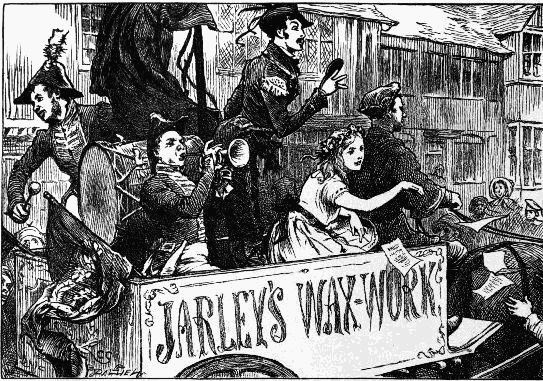

"You're the wax-work child, are you not?"—Chap. xxxi.

"You're the wax-work child, are you not?"—Chap. xxxi.

"Do you see this?"—Chap. xxxvi.

"Do you see this?"—Chap. xxxvi.

The old man stood helplessly among them for a little time—Chap. xiii.

The old man stood helplessly among them for a little time—Chap. xiii.

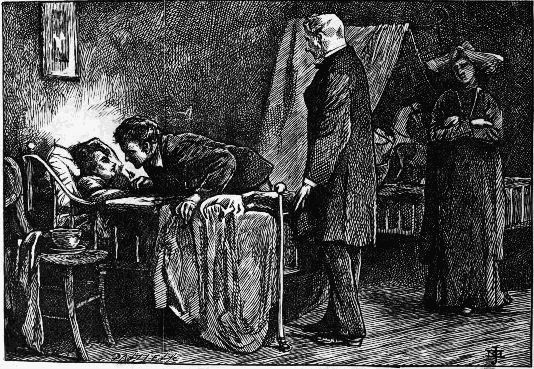

"She is quite exhausted," said the schoolmaster—Chap. xlvi.

"She is quite exhausted," said the schoolmaster—Chap. xlvi.

Both mother and daughter, trembling with terror and cold, . . . . obeyed Mr. Quilp's directions in

submissive silence—Chap. l.

Both mother and daughter, trembling with terror and cold, . . . . obeyed Mr. Quilp's directions in

submissive silence—Chap. l.

"Halloa!"—Chap. l.

"Halloa!"—Chap. l.

The child sat down in this old silent place—Chap. liii.

The child sat down in this old silent place—Chap. liii.

The air was, "Away with Melancholy"—Chap. lvlli.

The air was, "Away with Melancholy"—Chap. lvlli.

The Marchioness jumped up quickly, and clapped her hands—Chap. lxiv.

The Marchioness jumped up quickly, and clapped her hands—Chap. lxiv.

Tom immediately walked upon his hands to the window, and—if the expression be allowable—looked

in with his shoes—Chap. lxvii.

Tom immediately walked upon his hands to the window, and—if the expression be allowable—looked

in with his shoes—Chap. lxvii.

"Master!" he cried, stooping on one knee and catching at his hand. "Dear Master! speak to me!"—Chap. lxxi.

"Master!" he cried, stooping on one knee and catching at his hand. "Dear Master! speak to me!"—Chap. lxxi.

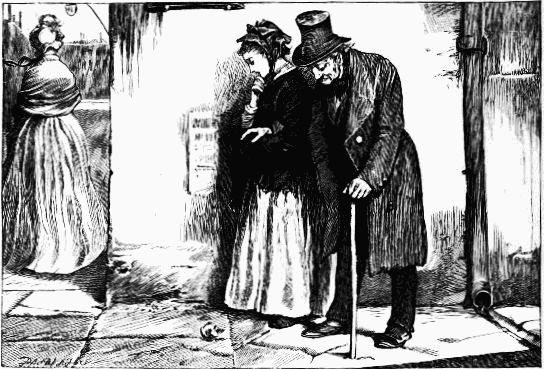

Two wretched people were more than once observed to crawl at dusk from the

inmost recesses of St. Giles's—Chap. lxxiii.

Two wretched people were more than once observed to crawl at dusk from the

inmost recesses of St. Giles's—Chap. lxxiii.

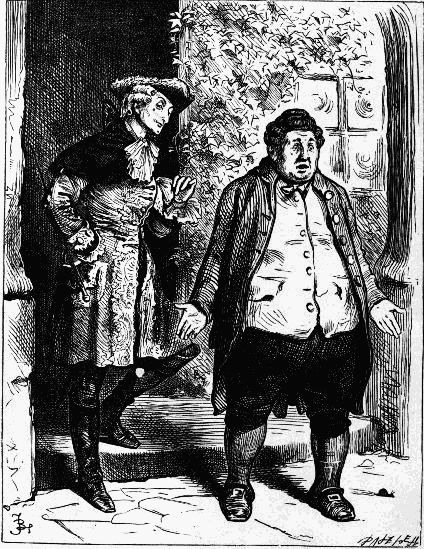

"Does the boy know what he's a-saying of!" cried the astonished John Willett—Chap. iii.

"Does the boy know what he's a-saying of!" cried the astonished John Willett—Chap. iii.

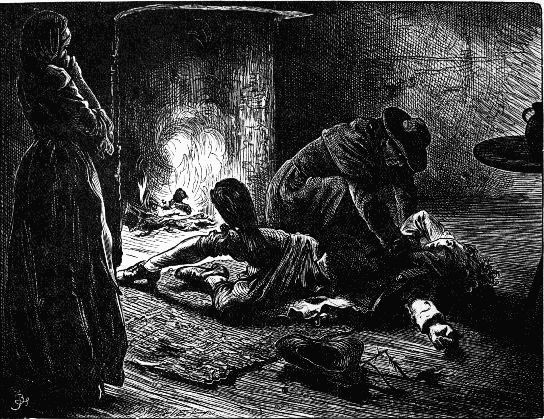

"I can't touch him!" cried the idiot, falling back and shuddering as

with a strong spasm; "he's bloody!"—Chap. iii.

"I can't touch him!" cried the idiot, falling back and shuddering as

with a strong spasm; "he's bloody!"—Chap. iii.

"If I am ever," said Mrs. V.,—not scolding, but in a sort of monotonous

remonstrance—"in spirits, if i am ever cheerful, if I am ever more

than usually disposed to be talkative and comfortable, this is the

way I am treated"—Chap. vii.

"If I am ever," said Mrs. V.,—not scolding, but in a sort of monotonous

remonstrance—"in spirits, if i am ever cheerful, if I am ever more

than usually disposed to be talkative and comfortable, this is the

way I am treated"—Chap. vii.

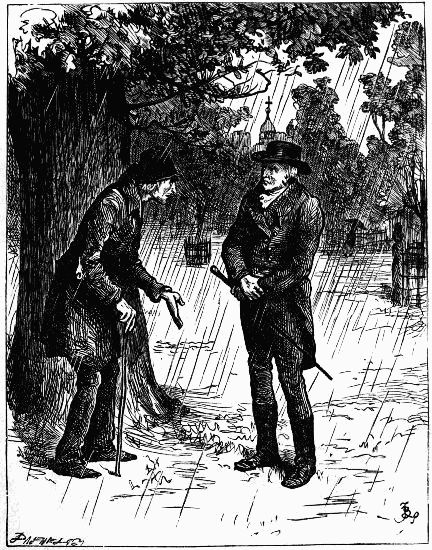

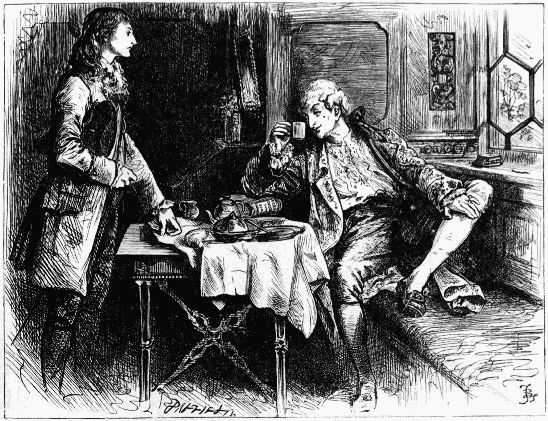

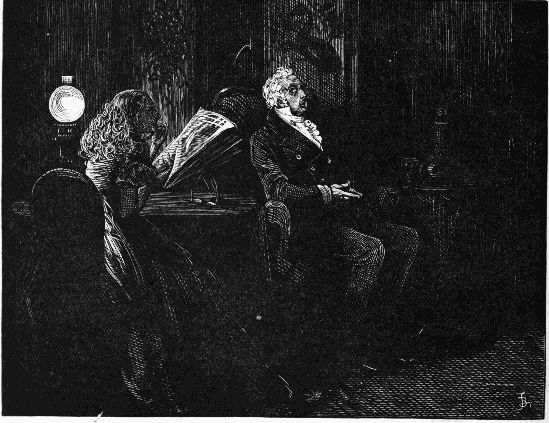

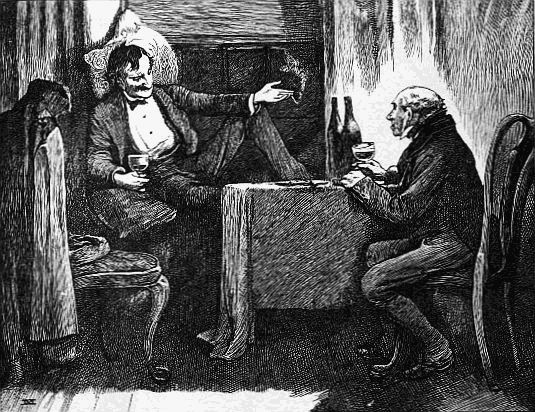

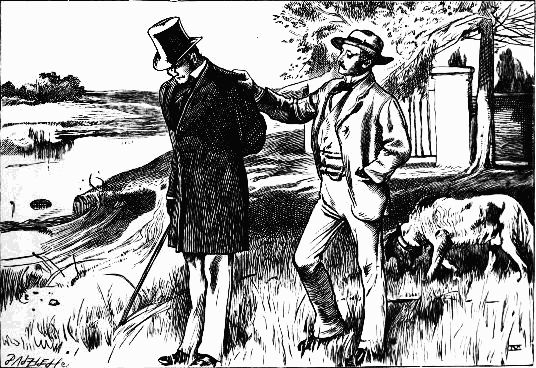

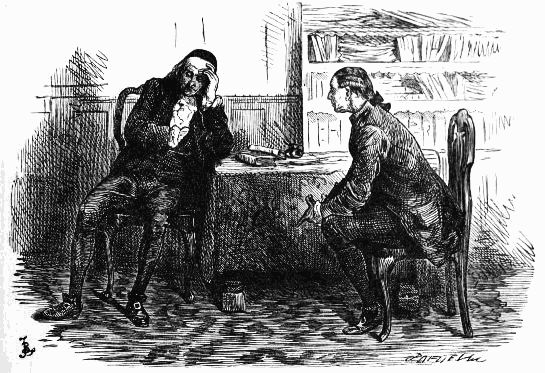

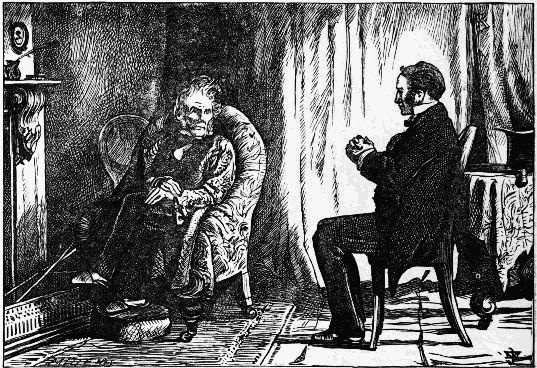

"Chester," said Mr. Haredale after a short silence, during which he had eyed his smiling face from

time to time intently, "you have the head and heart of an evil spirit in all matters of deception"—Chap. xii.

"Chester," said Mr. Haredale after a short silence, during which he had eyed his smiling face from

time to time intently, "you have the head and heart of an evil spirit in all matters of deception"—Chap. xii.

"He melts, I think. He goes like a drop of froth. You look at him, and there

he is. You look at him again, and—there he isn't"—Chap. x.

"He melts, I think. He goes like a drop of froth. You look at him, and there

he is. You look at him again, and—there he isn't"—Chap. x.

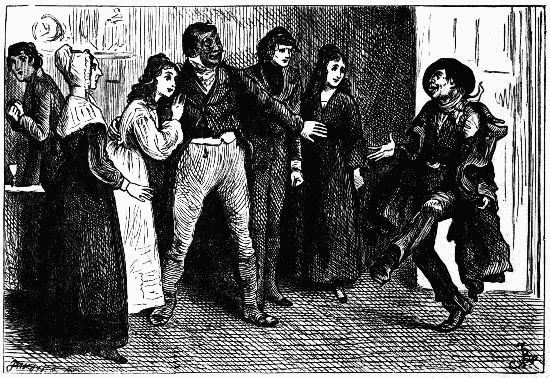

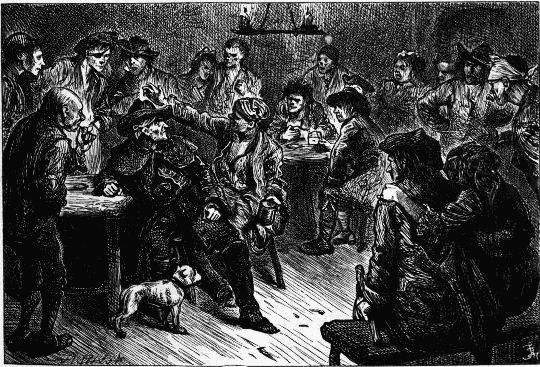

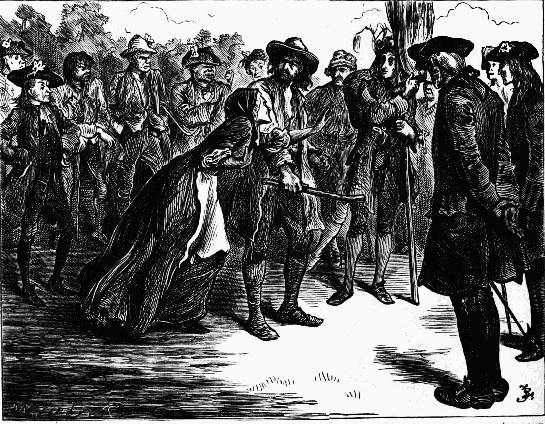

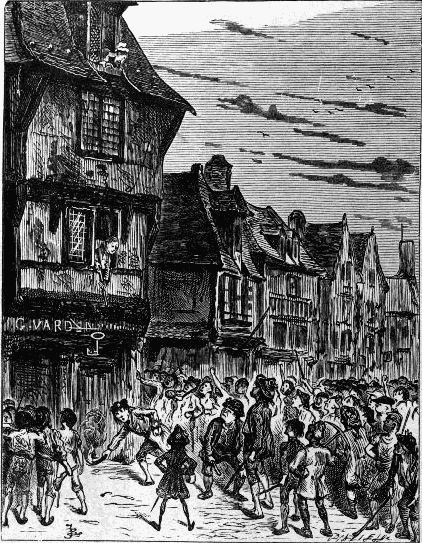

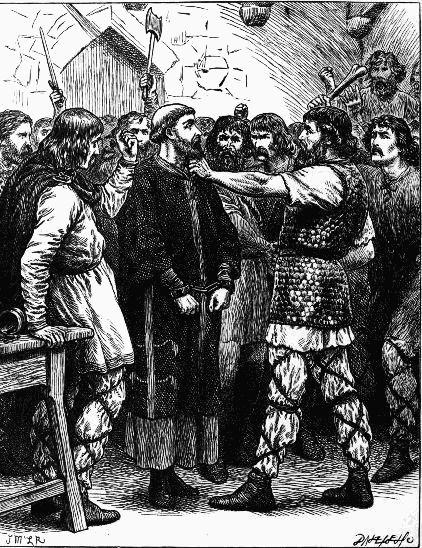

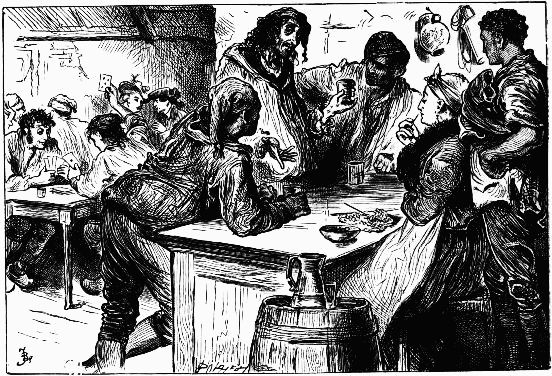

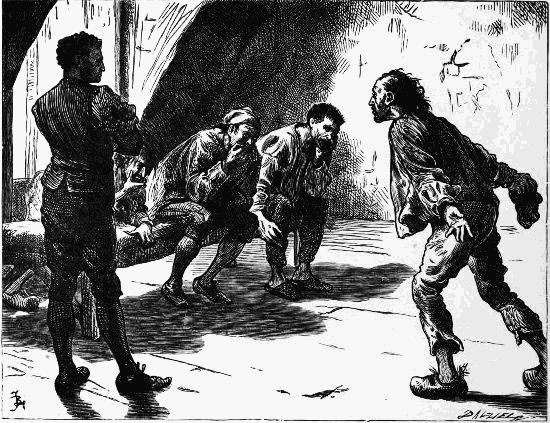

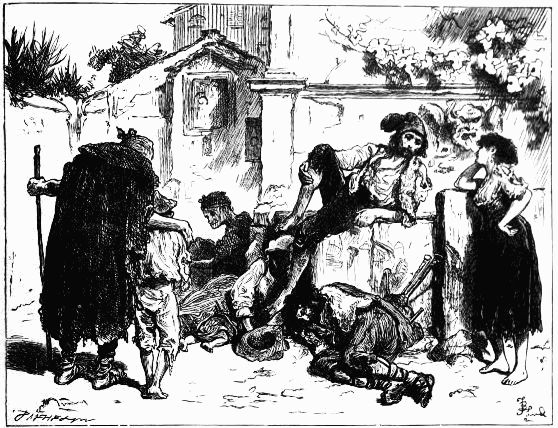

"Come, come, master," cried the fellow, urged on by the looks of his comrades, and slapping him on the

shoulder; "Be more companionable and communicative. Be more the gentleman in this good company"—Chap. xvi.

"Come, come, master," cried the fellow, urged on by the looks of his comrades, and slapping him on the

shoulder; "Be more companionable and communicative. Be more the gentleman in this good company"—Chap. xvi.

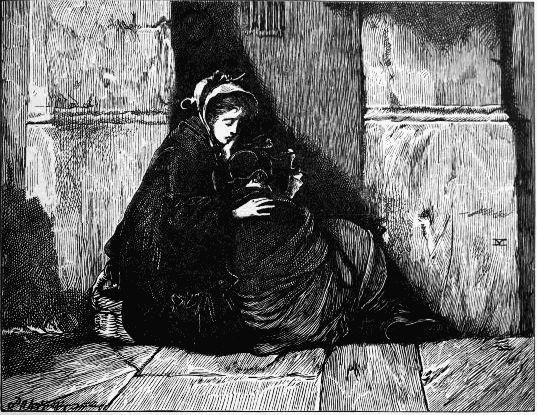

She sat here, thoughtful and apart, until their time was out—Chap. xxv.

She sat here, thoughtful and apart, until their time was out—Chap. xxv.

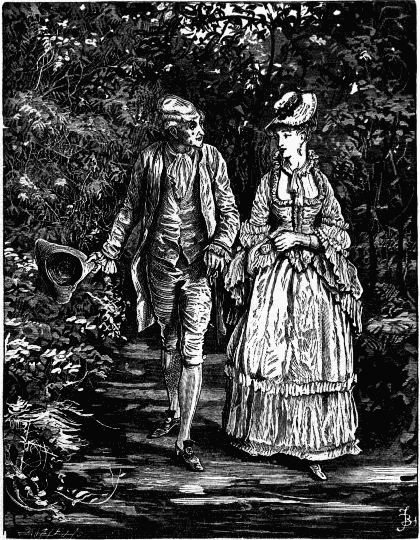

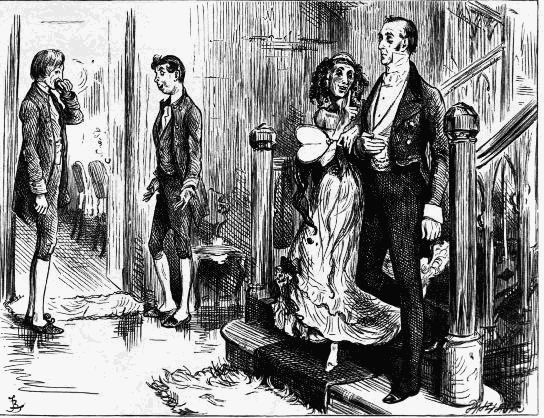

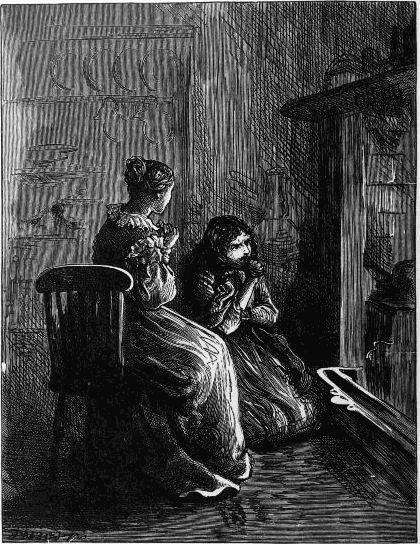

Emma Haredale and Dolly Varden—Chap. xx.

Emma Haredale and Dolly Varden—Chap. xx.

"Huff or no huff," said Mr. Tappertit, detaining her by the wrist. "What do

you mean, Jezebel! what were you going to say! Answer me!"—Chap. xxii.

"Huff or no huff," said Mr. Tappertit, detaining her by the wrist. "What do

you mean, Jezebel! what were you going to say! Answer me!"—Chap. xxii.

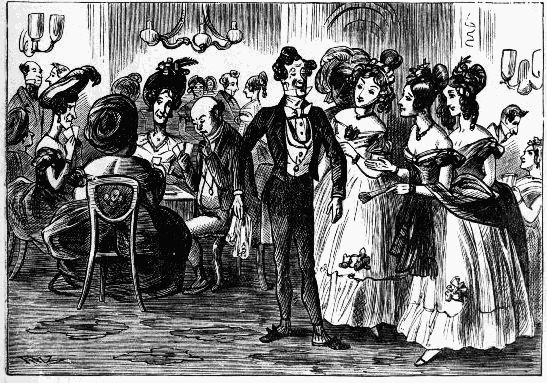

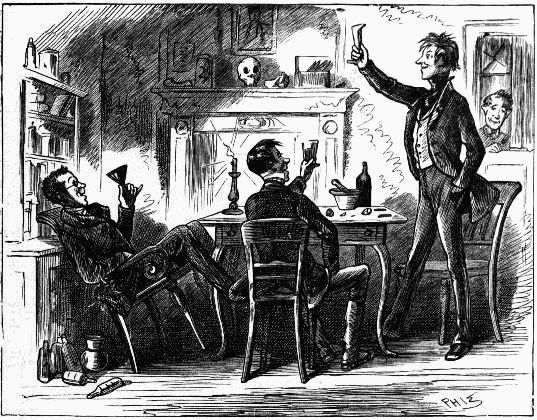

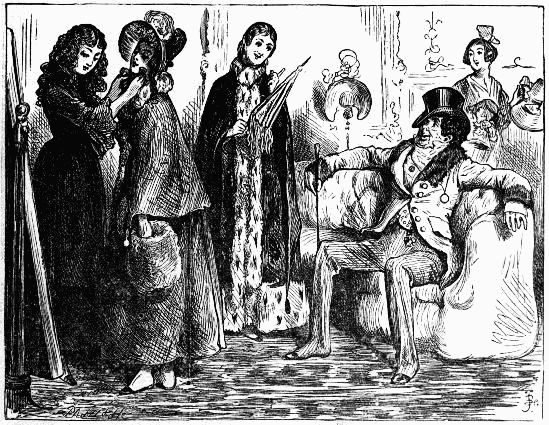

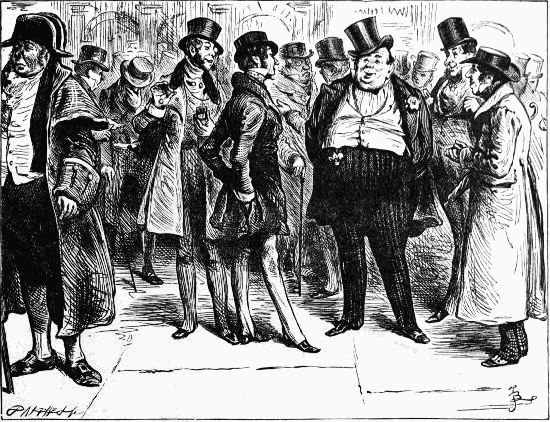

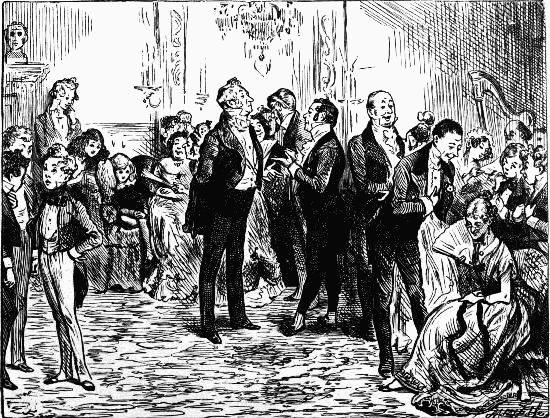

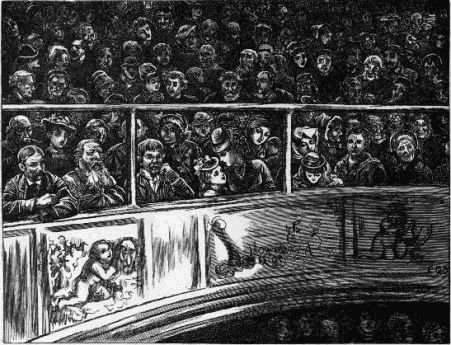

How the accomplished gentleman spent the evening in the midst of a dazzling and brilliant circle—Chap. xxiv.

How the accomplished gentleman spent the evening in the midst of a dazzling and brilliant circle—Chap. xxiv.

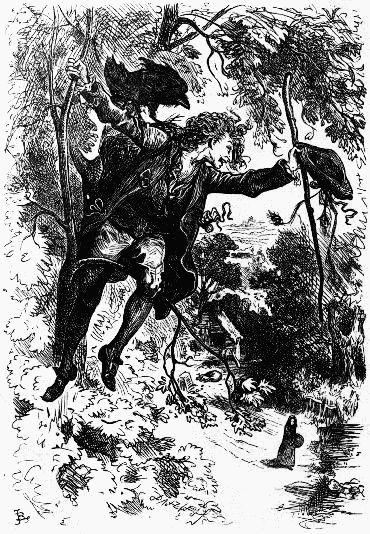

Now he would call to her from the topmost branch of some high tree

by the roadside—Chap. xxv.

Now he would call to her from the topmost branch of some high tree

by the roadside—Chap. xxv.

"I beg pardon—do I address Miss Haredale!"—Chap. xxix.

"I beg pardon—do I address Miss Haredale!"—Chap. xxix.

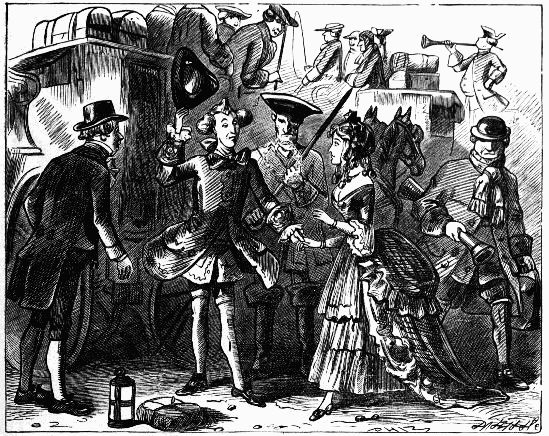

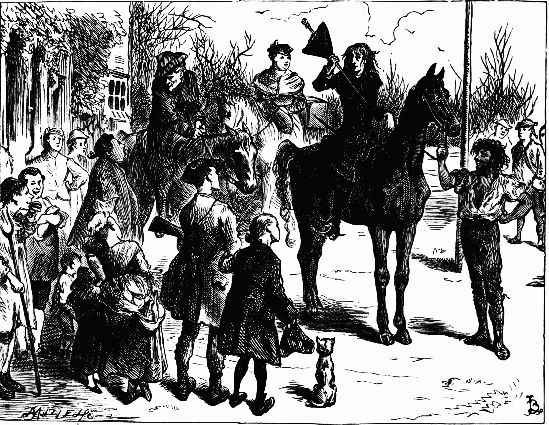

Lord George Gordon leaving the Maypole—Chap. xxxvii.

Lord George Gordon leaving the Maypole—Chap. xxxvii.

"If they're a dream," said Sim, "let sculptures have such wisions, and chisel'em

out when they wake. This is reality. Sleep has no such limbs as them"—Chap. xxxi.

"If they're a dream," said Sim, "let sculptures have such wisions, and chisel'em

out when they wake. This is reality. Sleep has no such limbs as them"—Chap. xxxi.

A nice trio—Chap. xxxix.

A nice trio—Chap. xxxix.

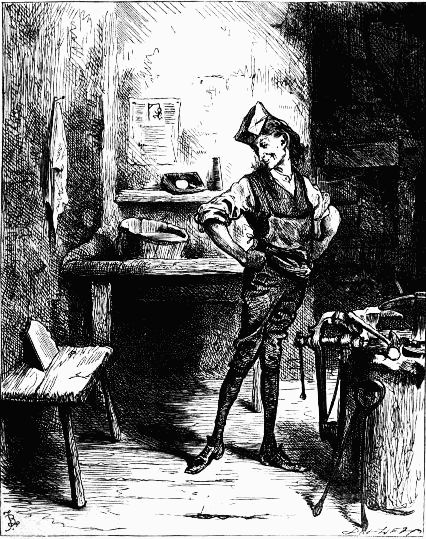

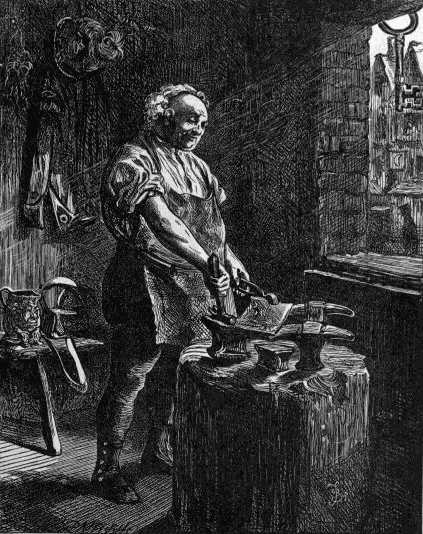

Gabriel Varden—Chap. xii.

Gabriel Varden—Chap. xii.

"In the name of God no!" shrieked the widow, darting forward. "Barnaby—my lord—see—he'll come

back—Barnaby—Barnaby!"—Chap. xlviii.

"In the name of God no!" shrieked the widow, darting forward. "Barnaby—my lord—see—he'll come

back—Barnaby—Barnaby!"—Chap. xlviii.

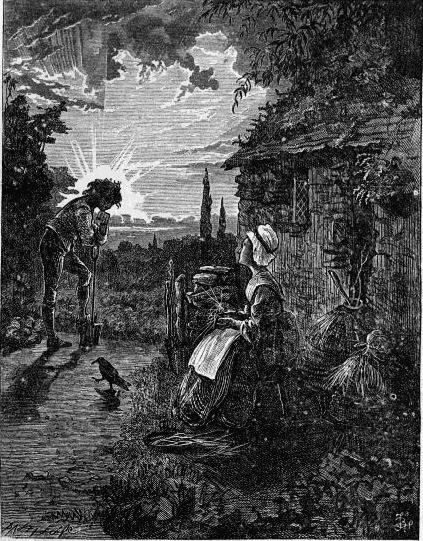

"A brave evening, mother! If we had chinking in our pockets but a few specks

of that gold which is piled up yonder in the sky, we should be rich for life"—Chap. xlv.

"A brave evening, mother! If we had chinking in our pockets but a few specks

of that gold which is piled up yonder in the sky, we should be rich for life"—Chap. xlv.

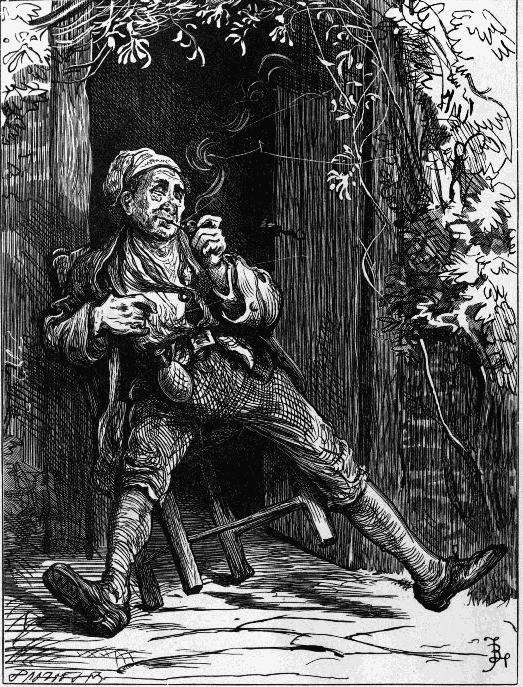

Then seating himself under a spreading honeysuckle, and stretching his legs across the threshold

so that no person could pass in or out without his knowledge, he took from his pocket a pipe, flint,

steel, and tinder-box, and began to smoke—Chap. xlv.

Then seating himself under a spreading honeysuckle, and stretching his legs across the threshold

so that no person could pass in or out without his knowledge, he took from his pocket a pipe, flint,

steel, and tinder-box, and began to smoke—Chap. xlv.

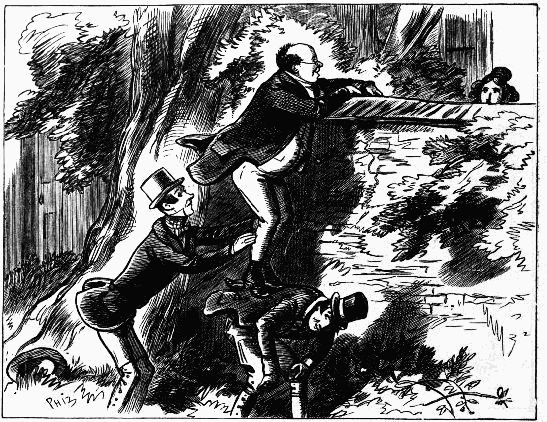

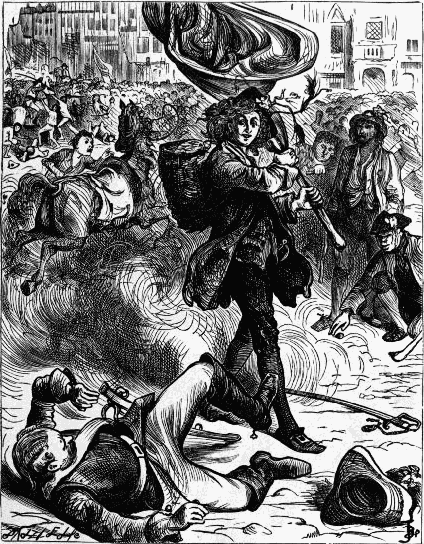

The pole swept the air above the people's heads, and the man's saddle was empty

in an instant—Chap. xlix.

The pole swept the air above the people's heads, and the man's saddle was empty

in an instant—Chap. xlix.

"You have been drinking," said the locksmith—Chap. li.

"You have been drinking," said the locksmith—Chap. li.

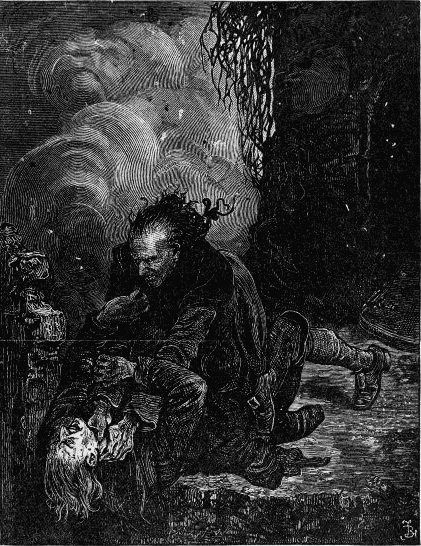

Flung itself upon the foremost one, knelt down upon its breast, and clutched

its throat with both hands—Chap. lvi.

Flung itself upon the foremost one, knelt down upon its breast, and clutched

its throat with both hands—Chap. lvi.

Looked moodily on as she flew to Miss Haredale's side—Chap. lix.

Looked moodily on as she flew to Miss Haredale's side—Chap. lix.

"Will you come?"

"Will you come?"

"Stop!" cried the locksmith, in a voice that made them falter—presenting, as

he spoke, a gun. "Let an old man do that. You can spare him better"—Chap. lxiii.

"Stop!" cried the locksmith, in a voice that made them falter—presenting, as

he spoke, a gun. "Let an old man do that. You can spare him better"—Chap. lxiii.

"No offence, no offence," said that personage in a conciliatory tone, as Hugh stopped in his draught

and eyed him, with no pleasant look from head to foot—Chap. lxix.

"No offence, no offence," said that personage in a conciliatory tone, as Hugh stopped in his draught

and eyed him, with no pleasant look from head to foot—Chap. lxix.

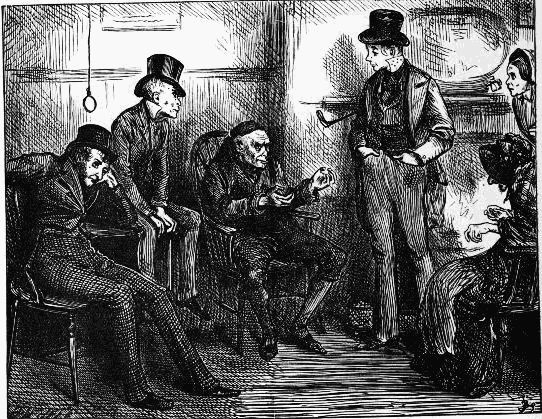

"You ought to be the best instead of the worst," said Hugh, stopping before him. "Ha, ha, ha! see the

hangman when it comes home to him!"—Chap. lxxvi.

"You ought to be the best instead of the worst," said Hugh, stopping before him. "Ha, ha, ha! see the

hangman when it comes home to him!"—Chap. lxxvi.

"I shall bless your name," sobbed the locksmith's little daughter, "as long

as I live"—Chap. lxxii.

"I shall bless your name," sobbed the locksmith's little daughter, "as long

as I live"—Chap. lxxii.

Sat the unhappy author of all—Lord George Gordon—Chap. lxxiii.

Sat the unhappy author of all—Lord George Gordon—Chap. lxxiii.

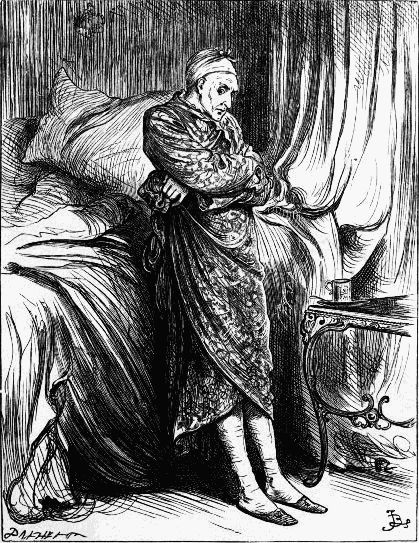

He rose from his bed with a heavy sigh, and wrapped himself in his morning

gown. "So she kept her word," he said, "and was constant to her threat!"—Chap. lxxv.

He rose from his bed with a heavy sigh, and wrapped himself in his morning

gown. "So she kept her word," he said, "and was constant to her threat!"—Chap. lxxv.

Reclining, in an easy attitude, with his back against a tree, and contemplating the ruin with an

expression of pleasure—Chap. lxxxi.

Reclining, in an easy attitude, with his back against a tree, and contemplating the ruin with an

expression of pleasure—Chap. lxxxi.

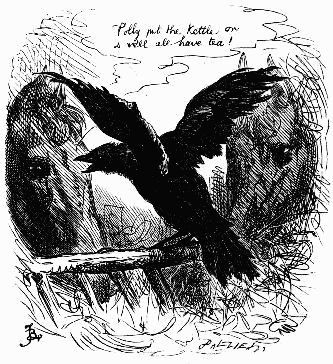

Grip the Raven—Chap. the last.

Grip the Raven—Chap. the last.

.

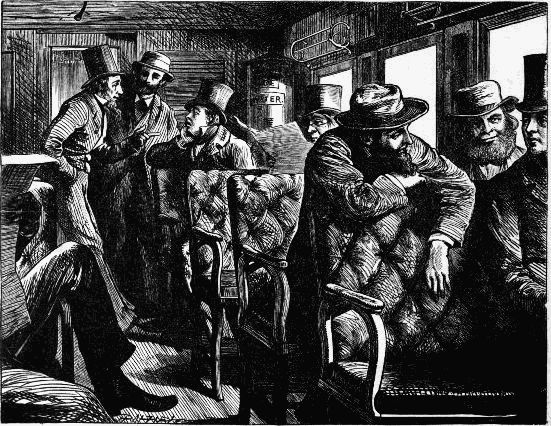

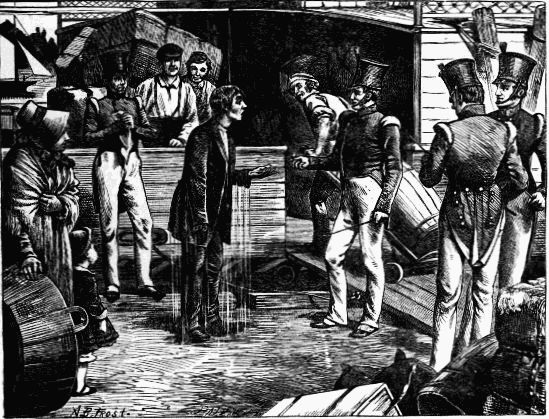

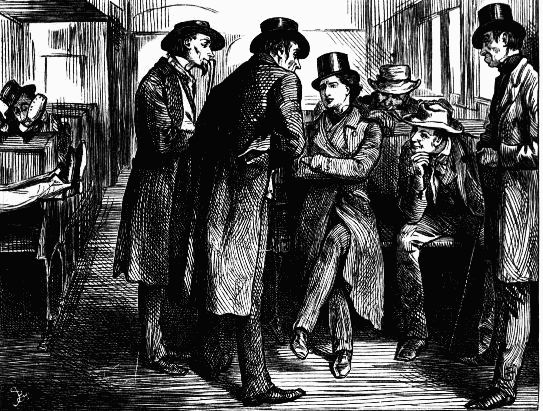

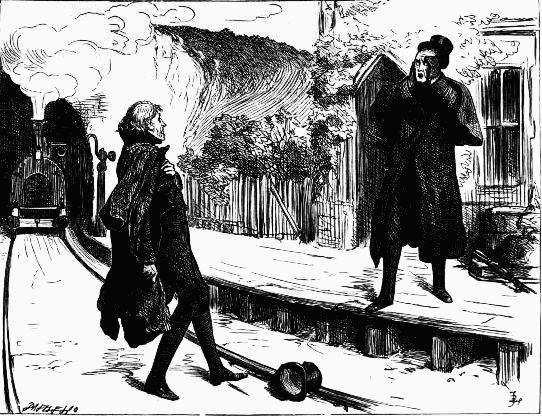

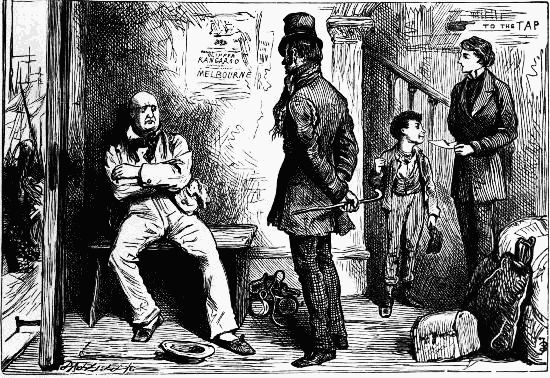

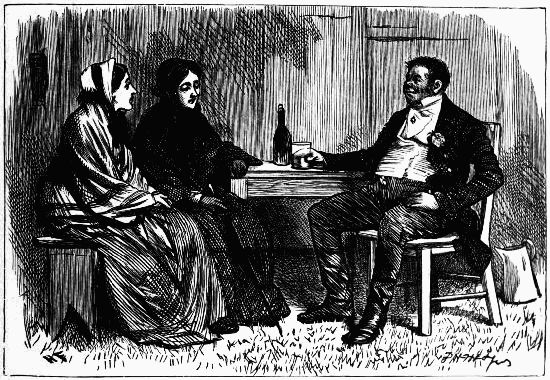

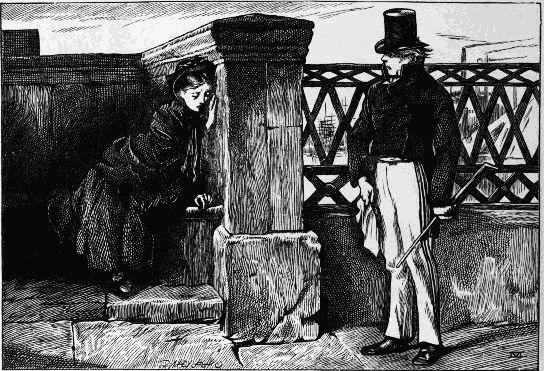

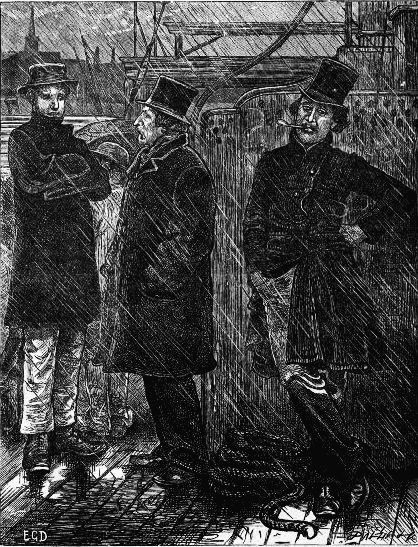

Railway dialogue—Chap. v.

Railway dialogue—Chap. v.

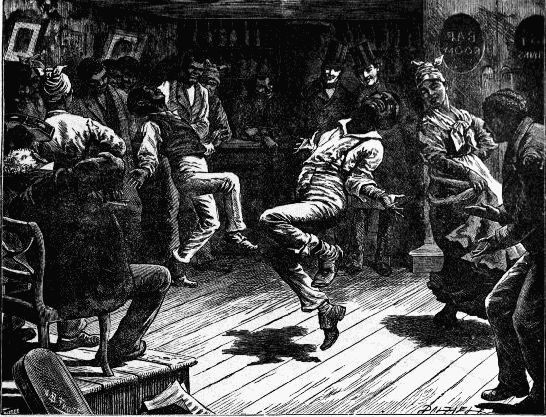

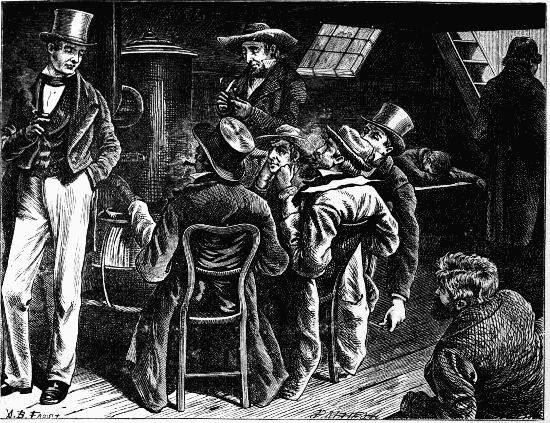

In the White House—Chap. vii

In the White House—Chap. vii

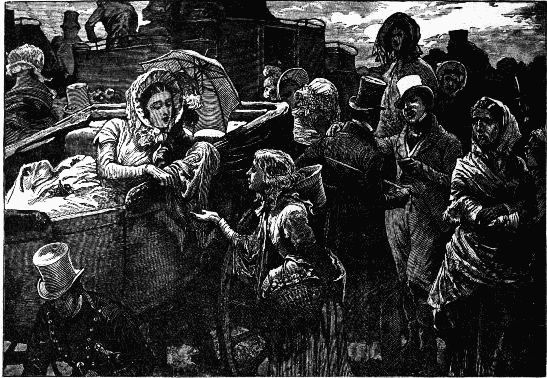

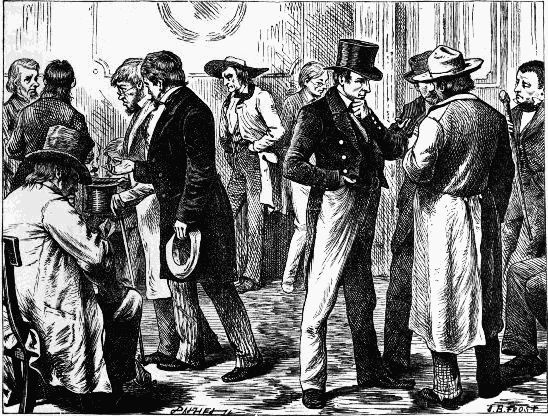

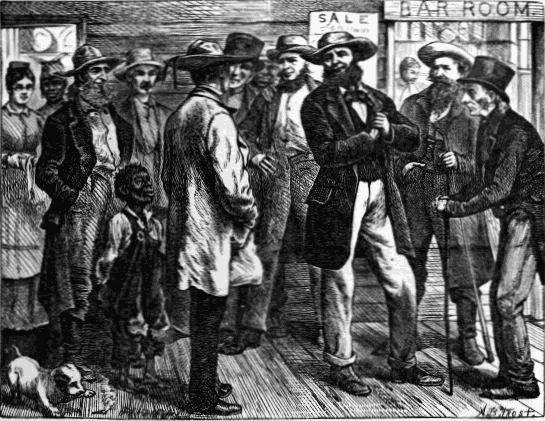

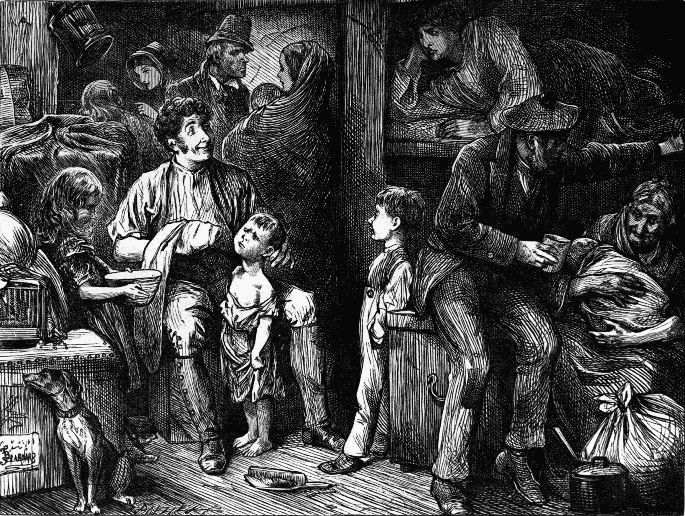

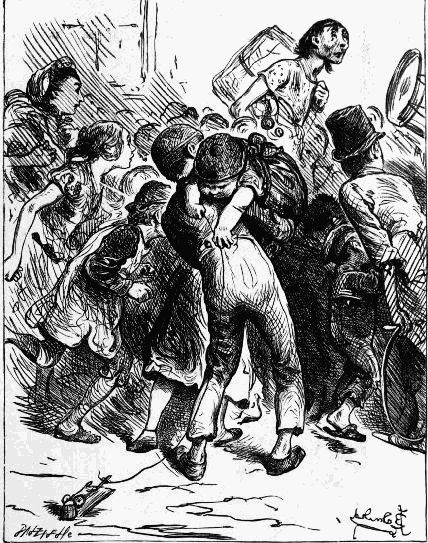

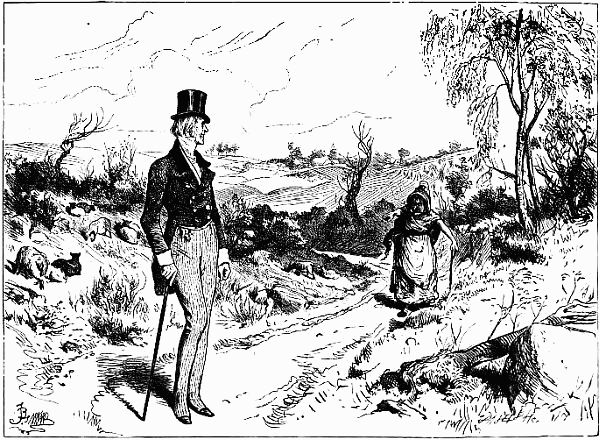

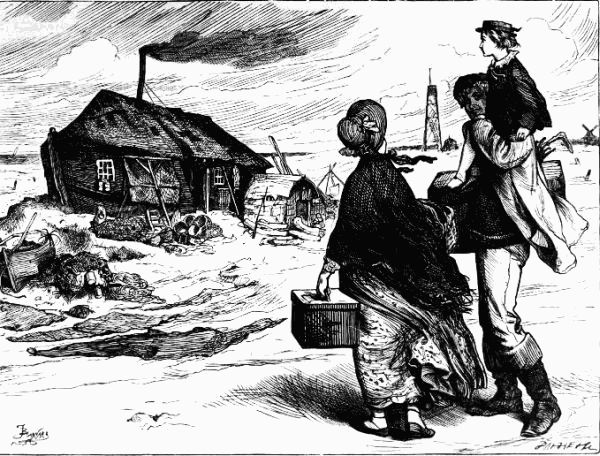

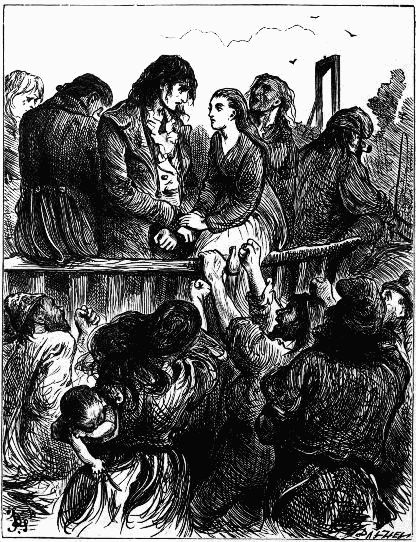

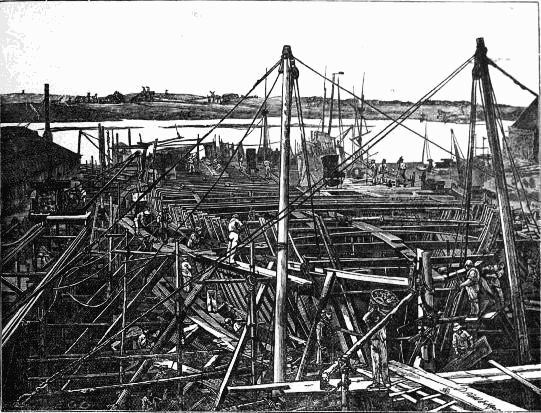

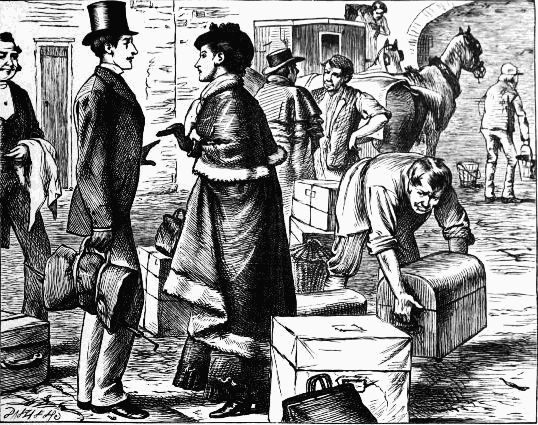

Emigrants—Chap. xi.

Emigrants—Chap. xi.

And having his wet pipe presented to him, etc.—Chap. xv.

And having his wet pipe presented to him, etc.—Chap. xv.

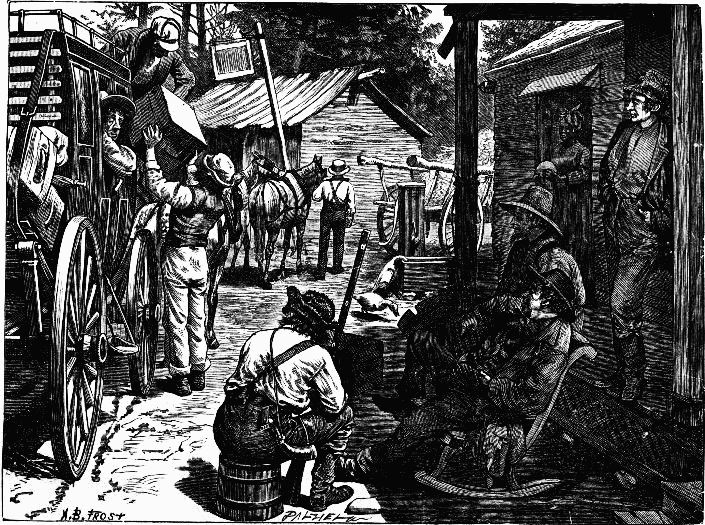

As the coach stops a gentleman in a straw hat looks out of the window—Chap. xiv.

As the coach stops a gentleman in a straw hat looks out of the window—Chap. xiv.

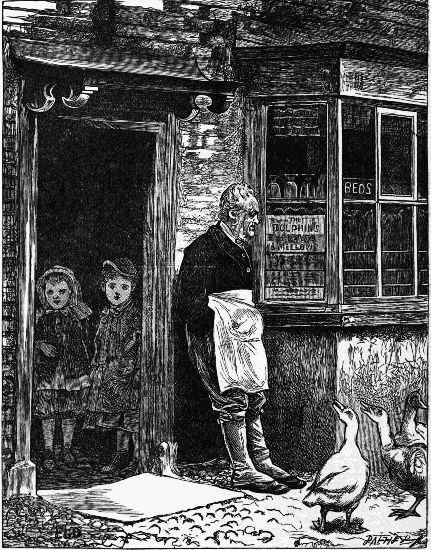

Mr. Pecksniff, looking sweetly over the half-door of the par, and into the vista of snug privacy

beyond, murmured, "Good evening, Mrs. Lupin"—Chap. iii.

Mr. Pecksniff, looking sweetly over the half-door of the par, and into the vista of snug privacy

beyond, murmured, "Good evening, Mrs. Lupin"—Chap. iii.

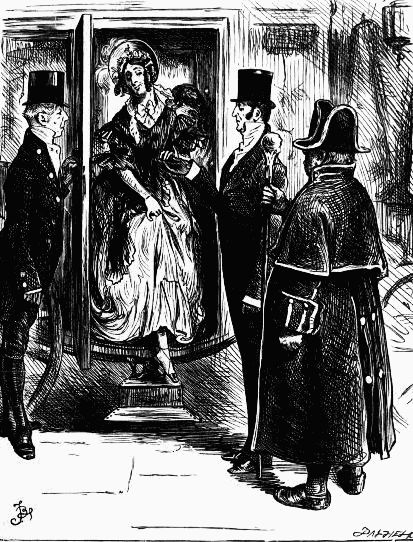

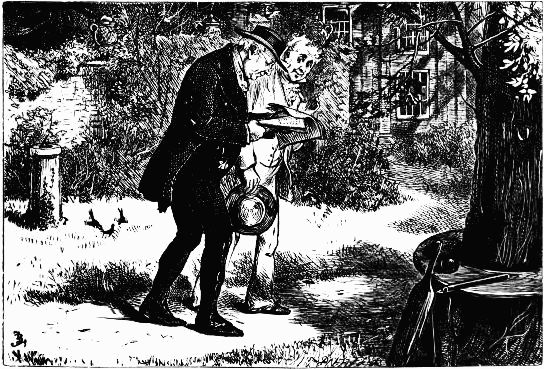

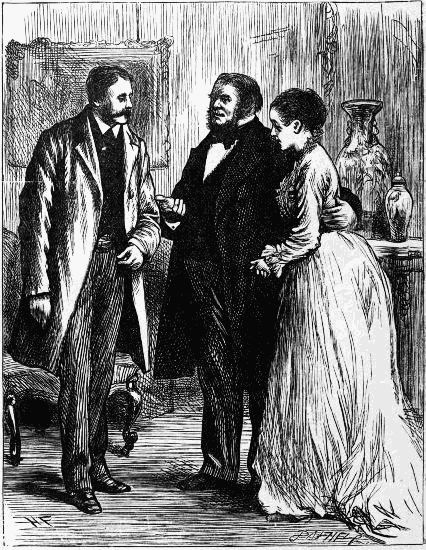

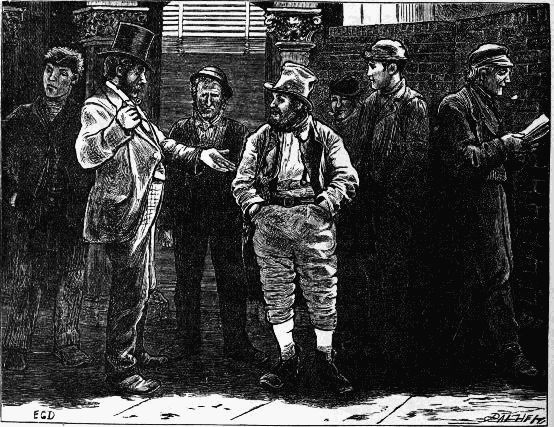

Mr. Pecksniff is introduced to a relative by Mr. Tigg—Chap. iv.

Mr. Pecksniff is introduced to a relative by Mr. Tigg—Chap. iv.

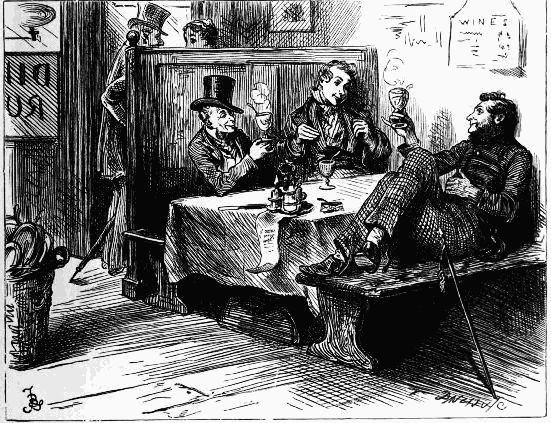

"Let us be merry." Here he took a captain's biscuit—Chap. v.

"Let us be merry." Here he took a captain's biscuit—Chap. v.

"Oh Chiv, Chiv," murmured Mr. Tigg, "you have a nobly independent nature, Chiv"—Chap. vii.

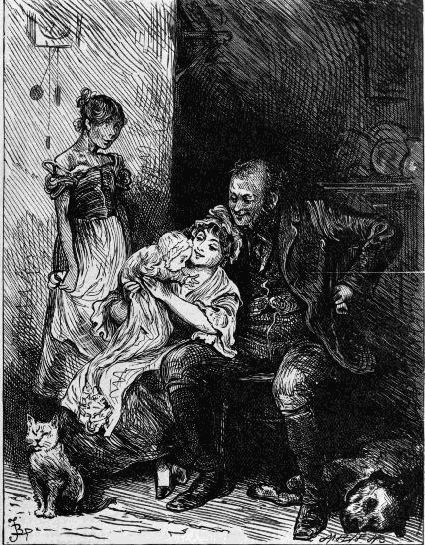

"Oh Chiv, Chiv," murmured Mr. Tigg, "you have a nobly independent nature, Chiv"—Chap. vii.

"You're a pair of Whittingtons, gents, without the cat, . . . My name is Tigg; how do you do?"—Chap. vii.

"You're a pair of Whittingtons, gents, without the cat, . . . My name is Tigg; how do you do?"—Chap. vii.

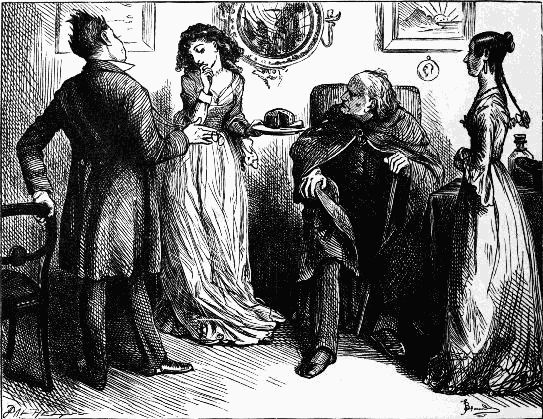

"Do not repine, my friends," said Mr. Pecksniff, tenderly. "Do not weep for me. It is chronic"—Chap. ix.

"Do not repine, my friends," said Mr. Pecksniff, tenderly. "Do not weep for me. It is chronic"—Chap. ix.

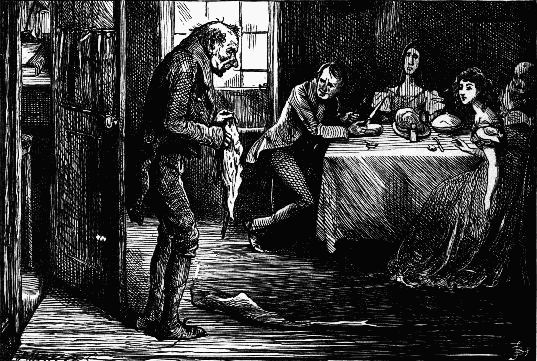

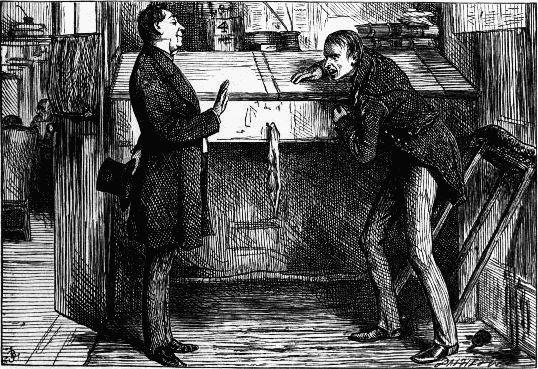

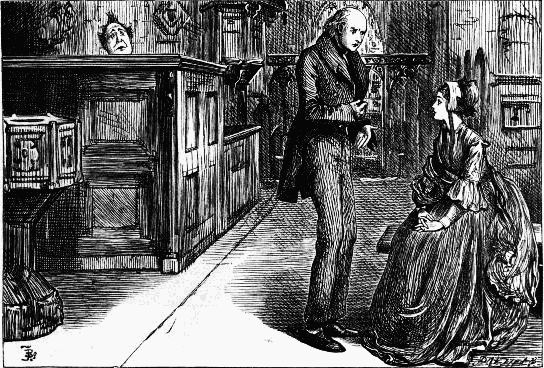

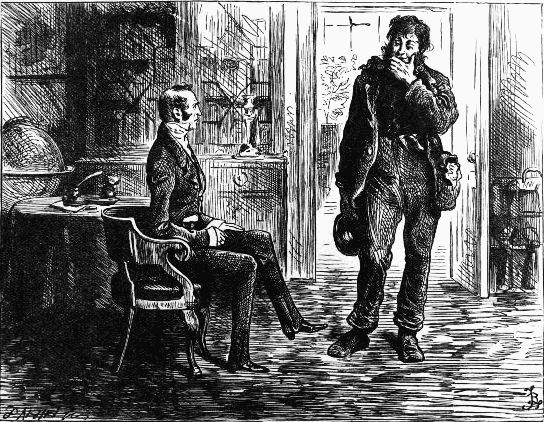

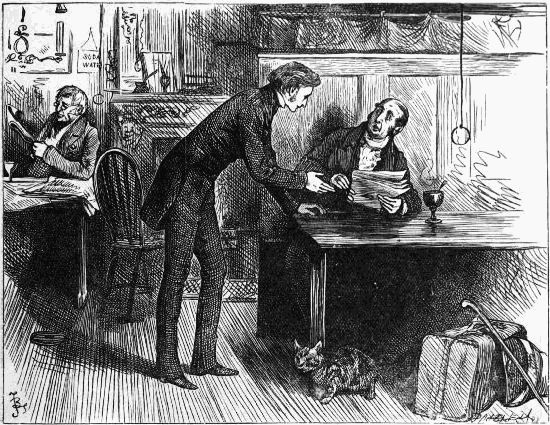

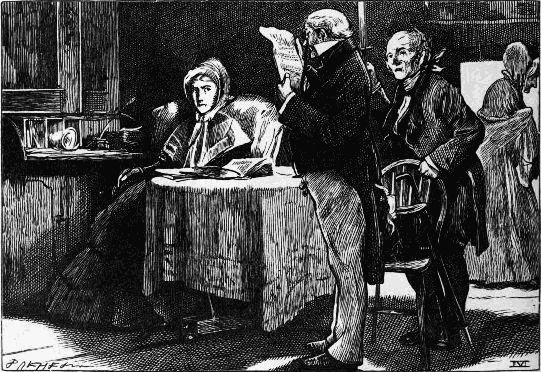

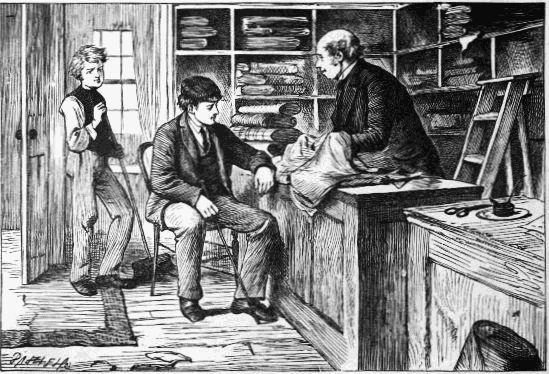

The door of a small glass office, which was partitioned off from the rest of the room, was slowly

opened, and a little blear-eyed, weazen-faced, ancient man came creeping out.—Chap. xi.

The door of a small glass office, which was partitioned off from the rest of the room, was slowly

opened, and a little blear-eyed, weazen-faced, ancient man came creeping out.—Chap. xi.

"I'm going up," observed the driver; "Hounslow, ten miles this side London"—Chap. xiii.

"I'm going up," observed the driver; "Hounslow, ten miles this side London"—Chap. xiii.

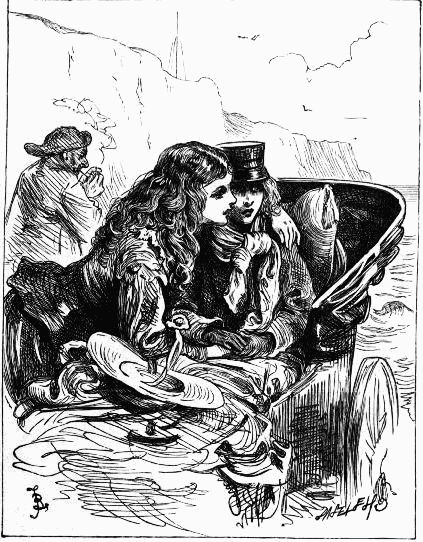

Seeing that there was no one near, and that Mark was still intent upon the fog, he not only

looked at her lips, but kissed them into the bargain—Chap. xiv.

Seeing that there was no one near, and that Mark was still intent upon the fog, he not only

looked at her lips, but kissed them into the bargain—Chap. xiv.

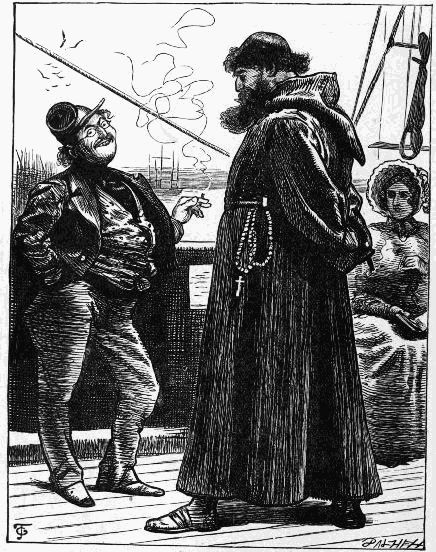

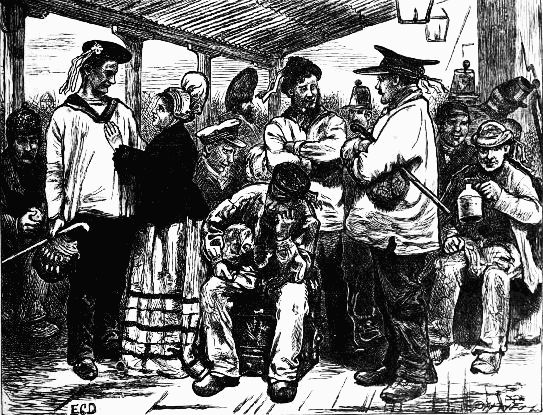

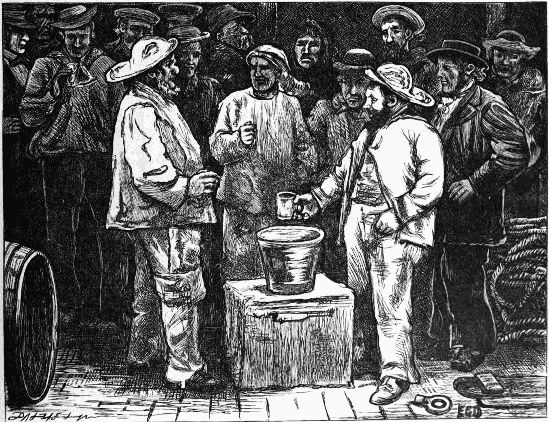

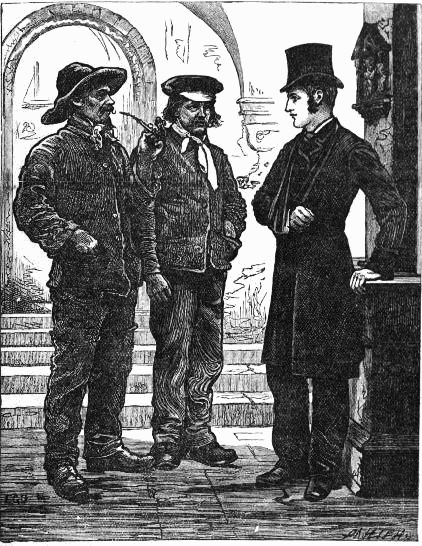

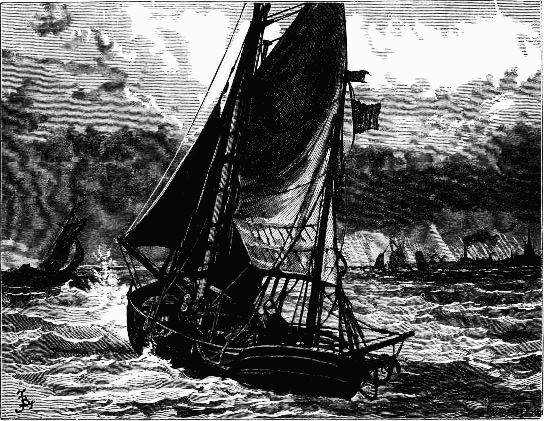

On board the "Screw"—Chap. xv.

On board the "Screw"—Chap. xv.

"You're the pleasantest fellow I have seen yet," said Martin, clapping him on the back, "and

give me a better appetite than bitters"—Chap. xvi.

"You're the pleasantest fellow I have seen yet," said Martin, clapping him on the back, "and

give me a better appetite than bitters"—Chap. xvi.

"Matter!" cried the voice of Mr. Pecksniff, as Pecksniff in the flesh smiled amiably upon him.

"The matter, Mr. Jonas!"—Chap. xviii.

"Matter!" cried the voice of Mr. Pecksniff, as Pecksniff in the flesh smiled amiably upon him.

"The matter, Mr. Jonas!"—Chap. xviii.

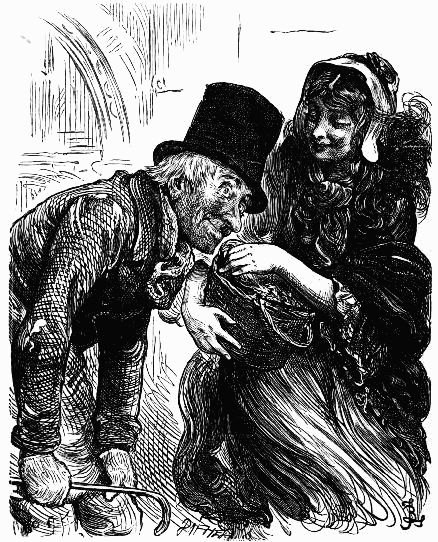

"Oh! I don't mind your pinching," grinned Jonas, "a bit"—Chap. xx.

"Oh! I don't mind your pinching," grinned Jonas, "a bit"—Chap. xx.

"Well, sir!" said the captain putting his hat a little more on one side, for it was rather tight

in the crown: "You're quite a public man I calc'late"—Chap. xxii.

"Well, sir!" said the captain putting his hat a little more on one side, for it was rather tight

in the crown: "You're quite a public man I calc'late"—Chap. xxii.

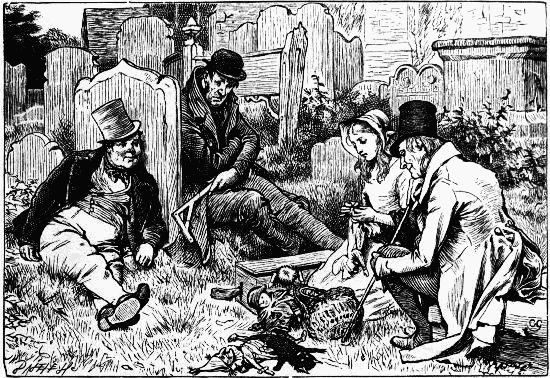

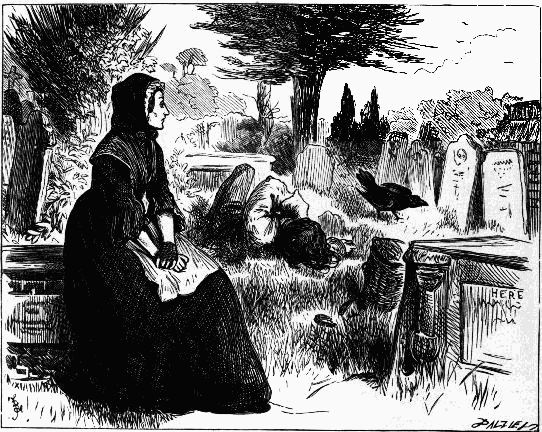

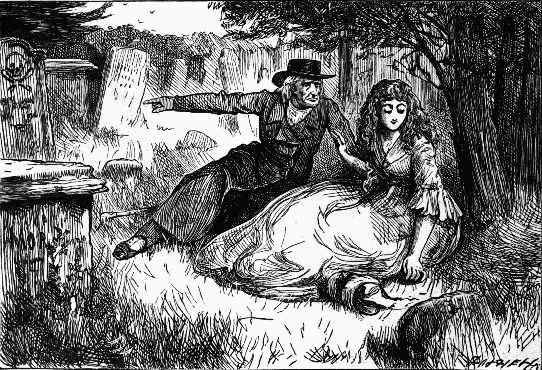

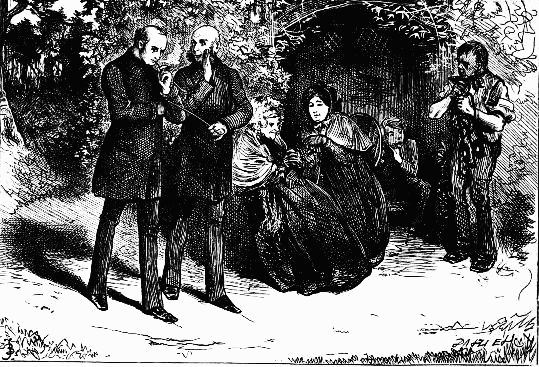

"Look about you," he said, pointing to the graves; "and remember that from your bridal hour to

the day which sees you brought as low as these, and laid in such a bed, there will be no appeal

against him!"—Chap. xxiv.

"Look about you," he said, pointing to the graves; "and remember that from your bridal hour to

the day which sees you brought as low as these, and laid in such a bed, there will be no appeal

against him!"—Chap. xxiv.

"There's nothin' he don't know; that's my opinion," observed Mrs. Gamp. "All the wickedness

of the world is print to him"—Chap. xxvi.

"There's nothin' he don't know; that's my opinion," observed Mrs. Gamp. "All the wickedness

of the world is print to him"—Chap. xxvi.

"Times is changed, ain't they! I say, how you've growed!"—Chap. xxviii.

"Times is changed, ain't they! I say, how you've growed!"—Chap. xxviii.

"I say," cried Tom, in great excitement, "He is a scoundrel and a villain! I don't care who he is,

I say he is a double-dyed and most intolerable villain"—Chap. xxxi.

"I say," cried Tom, in great excitement, "He is a scoundrel and a villain! I don't care who he is,

I say he is a double-dyed and most intolerable villain"—Chap. xxxi.

"Mr. Pinch," said Mr. Pecksniff, shaking his head, "Oh, Mr. Pinch! I wonder how you can look me in the face!"—Chap. xxxi.

"Mr. Pinch," said Mr. Pecksniff, shaking his head, "Oh, Mr. Pinch! I wonder how you can look me in the face!"—Chap. xxxi.

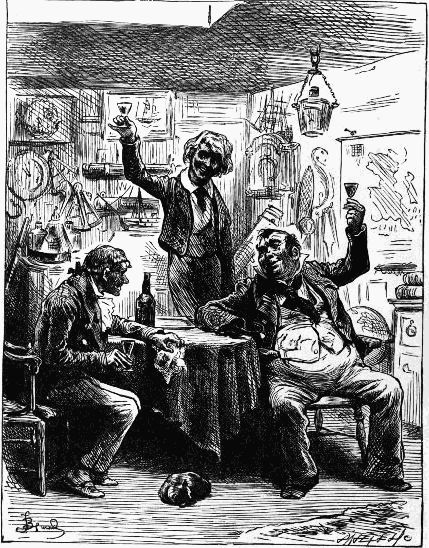

"Jolly"—Chap. xxxiii.

"Jolly"—Chap. xxxiii.

Mr. Pecksniff, placid, calm, but proud. Honestly proud . . . gently travelling across the disc,

as if he were a figure in a magic lantern—Chap. xxxv.

Mr. Pecksniff, placid, calm, but proud. Honestly proud . . . gently travelling across the disc,

as if he were a figure in a magic lantern—Chap. xxxv.

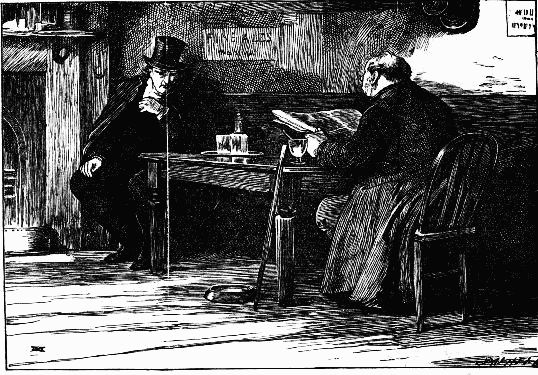

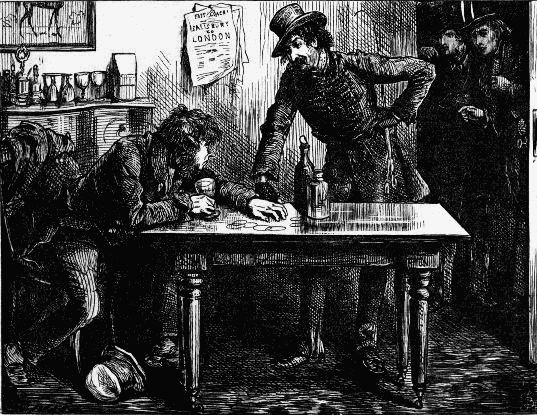

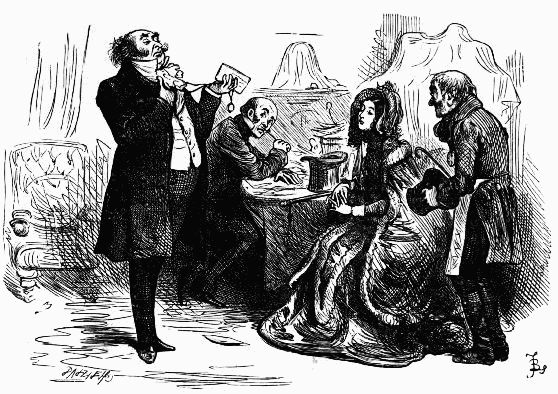

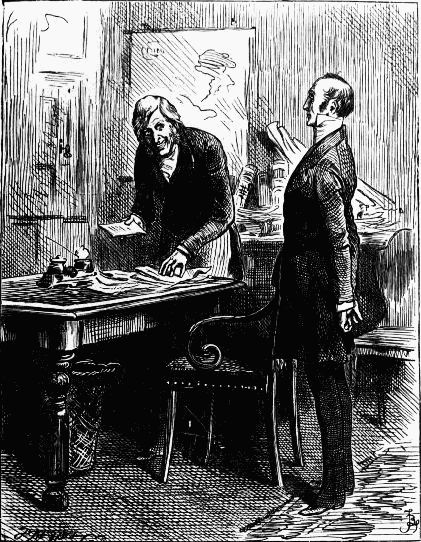

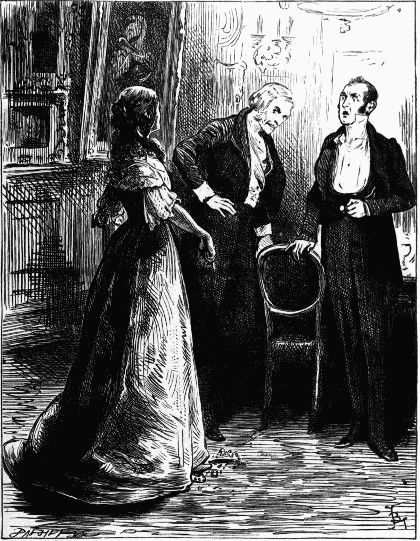

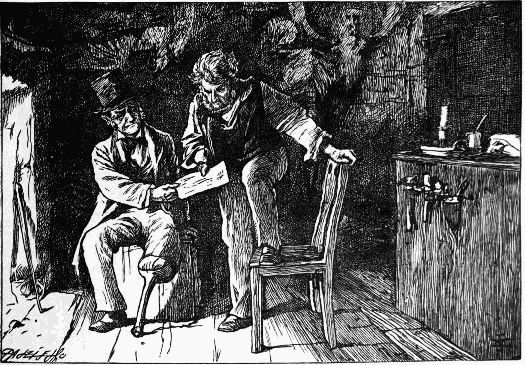

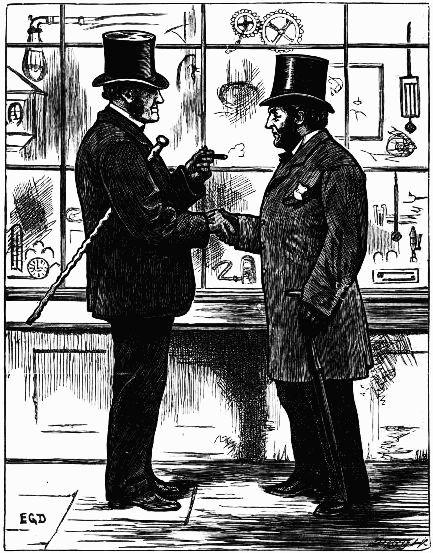

Mr. Nadgett produces the result of his private inquiries—Chap. xxxviii.

Mr. Nadgett produces the result of his private inquiries—Chap. xxxviii.

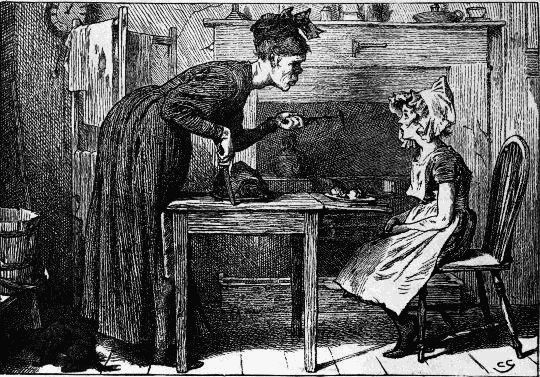

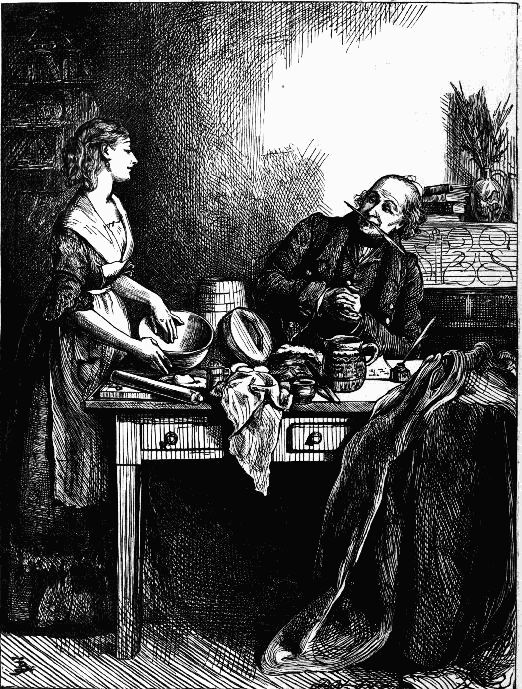

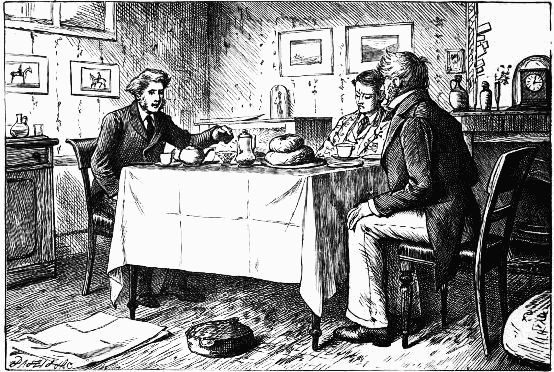

"I am going to begin, Tom. Don't you wonder why I butter the inside of the basin!" said his

busy little sister, "eh, Tom?"—Chap. xxxix.

"I am going to begin, Tom. Don't you wonder why I butter the inside of the basin!" said his

busy little sister, "eh, Tom?"—Chap. xxxix.

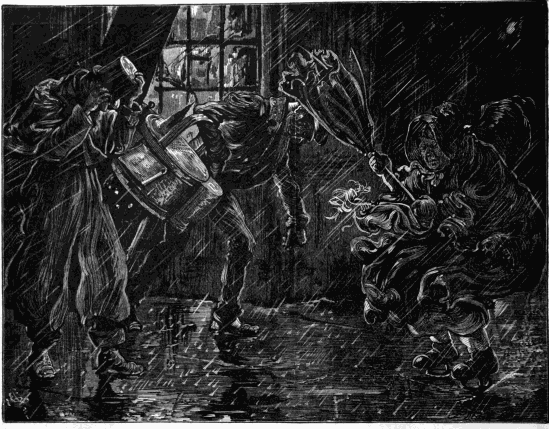

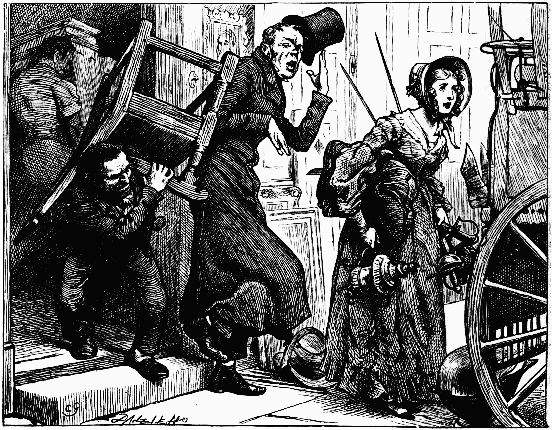

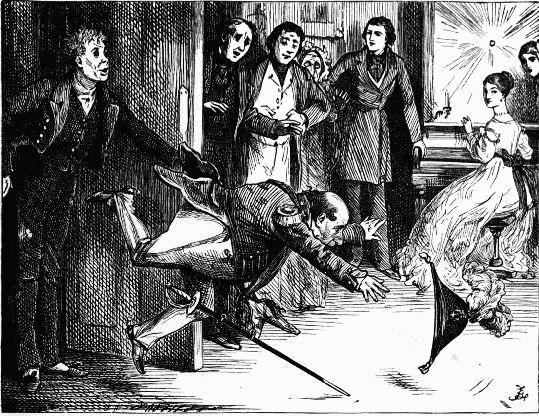

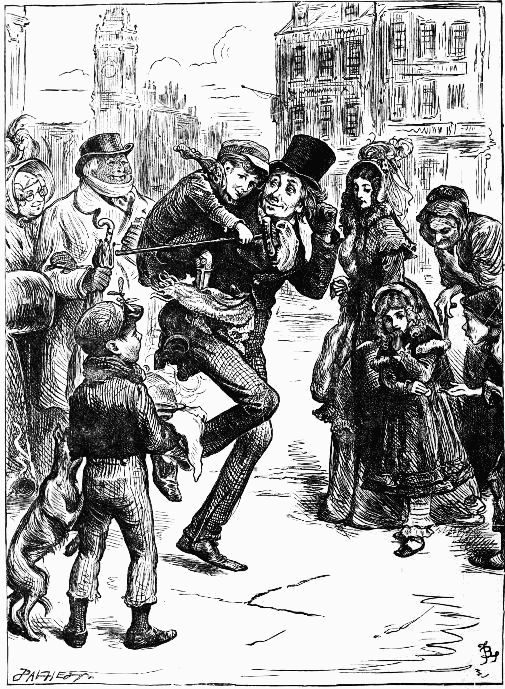

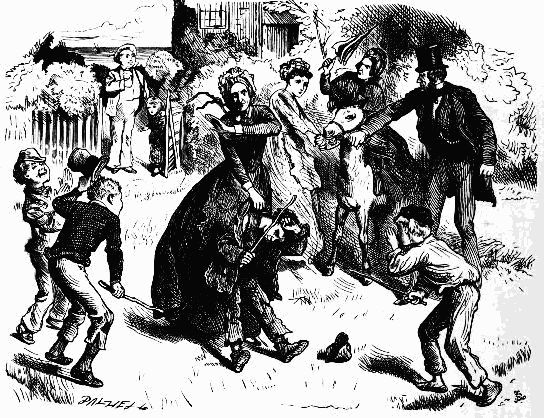

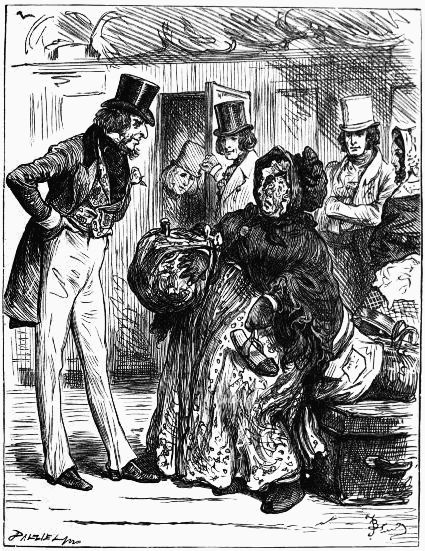

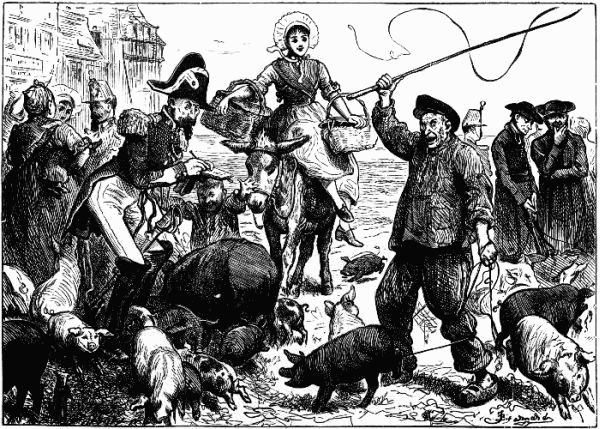

Mrs. Gamp creates a sensation with her umbrella—Chap. xl.

Mrs. Gamp creates a sensation with her umbrella—Chap. xl.

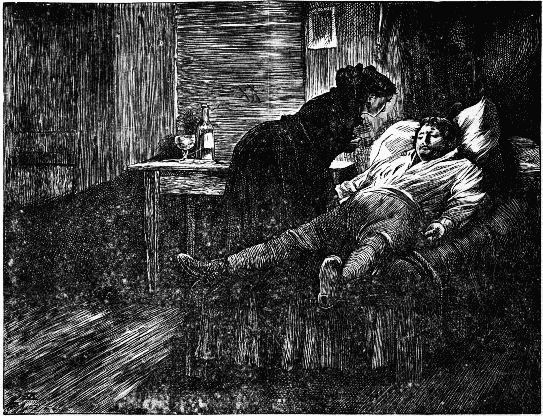

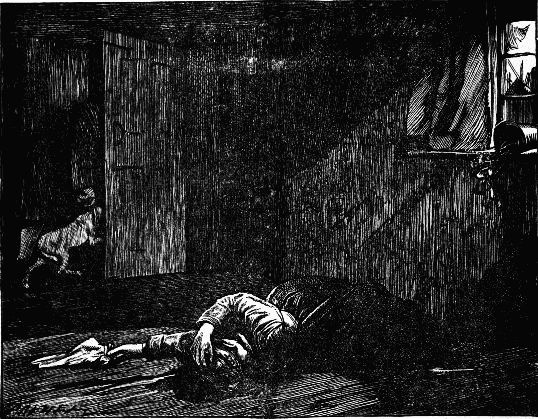

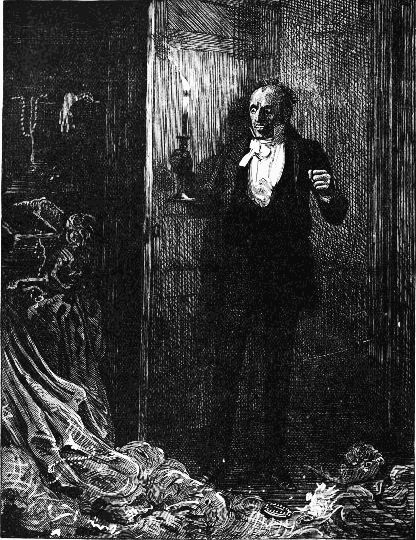

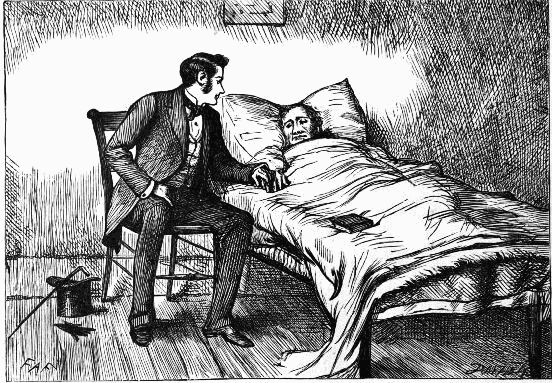

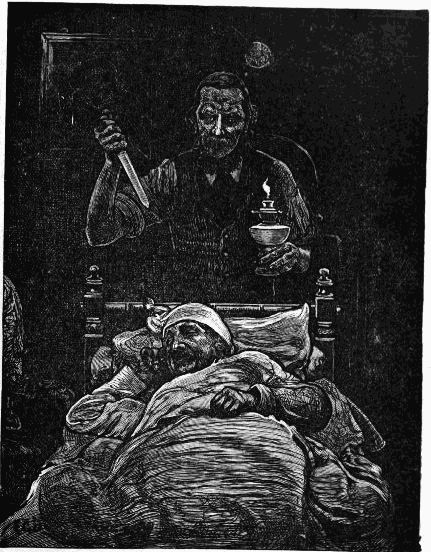

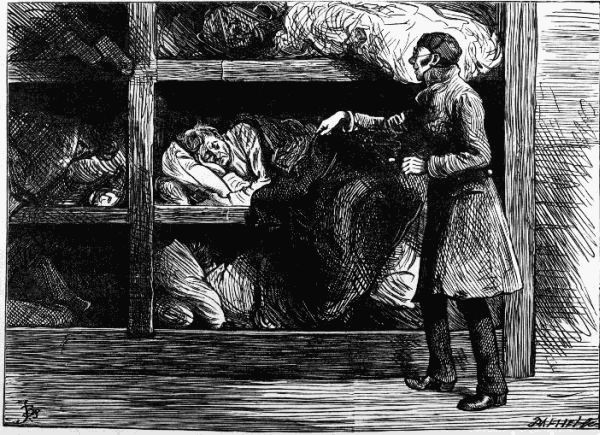

Awoke to find Jonas standing at his bedside watching him. And that very door wide open.—Chap. xlii.

Awoke to find Jonas standing at his bedside watching him. And that very door wide open.—Chap. xlii.

"Oh fie, fie!" cried Mr. Pecksniff. "You are very pleasant. That I am sure you don't! That

I am sure you don't! How can you, you know"—Chap. xliv.

"Oh fie, fie!" cried Mr. Pecksniff. "You are very pleasant. That I am sure you don't! That

I am sure you don't! How can you, you know"—Chap. xliv.

Mrs. Gamp favours the company with an exhibition of professional skill—Chap. xlvi.

Mrs. Gamp favours the company with an exhibition of professional skill—Chap. xlvi.

"Speak out!" said Martin, "and speak the truth"—Chap. xlvii.

"Speak out!" said Martin, "and speak the truth"—Chap. xlvii.

Brother and sister—Chap. l.

Brother and sister—Chap. l.

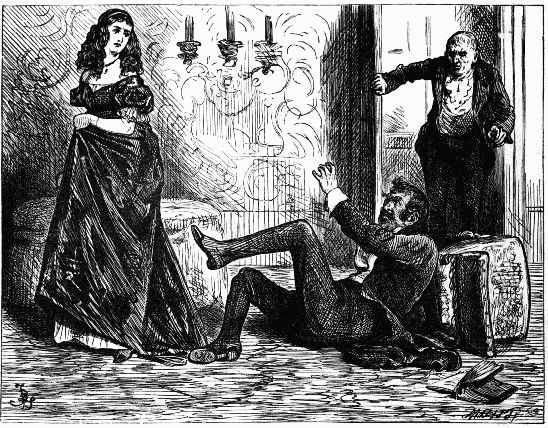

The fall of Pecksniff—Chap. lii.

The fall of Pecksniff—Chap. lii.

Tom's reverie—Chap. liv.

Tom's reverie—Chap. liv.

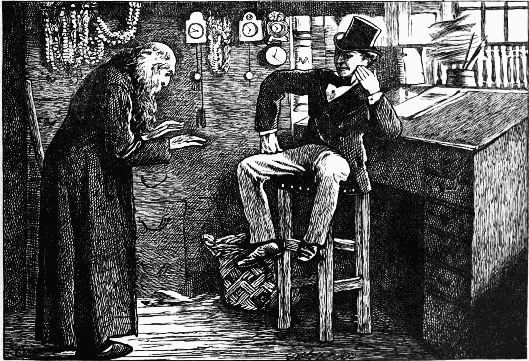

"It's not convenient," said Scrooge, "and it's not fair. If I was to stop half-a-crown

for it, you'd think yourself ill used, I'll be bound!"—A Christmas Carol,

Stave i.

"It's not convenient," said Scrooge, "and it's not fair. If I was to stop half-a-crown

for it, you'd think yourself ill used, I'll be bound!"—A Christmas Carol,

Stave i.

Marley's Ghost—A Christmas Carol, Stave i.

Marley's Ghost—A Christmas Carol, Stave i.

He had been Tim's blood-horse all the way from church, and had come home

rampant—A Christmas Carol, Stave iii.

He had been Tim's blood-horse all the way from church, and had come home

rampant—A Christmas Carol, Stave iii.

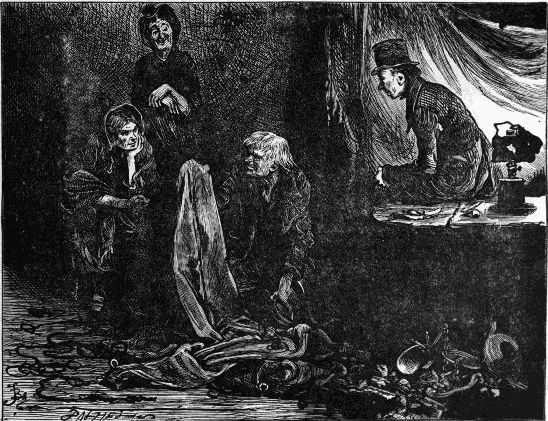

"What do you call this!" said Joe, "bed curtains!"—A Christmas Carol, Stave iv.

"What do you call this!" said Joe, "bed curtains!"—A Christmas Carol, Stave iv.

"No," said Toby, after another sniff. "It's—it's mellower than polonies.

It's very nice. It improves every moment. It's too decided for trotters.

An't it!"—The Chimes, First Quarter

"No," said Toby, after another sniff. "It's—it's mellower than polonies.

It's very nice. It improves every moment. It's too decided for trotters.

An't it!"—The Chimes, First Quarter

The poor man's friend.—The Chimes, Second Quarter

The poor man's friend.—The Chimes, Second Quarter

"Never more, Meg; never more! Here! here! Close to you, holding to you,

feeling your dear breath upon my face!"—The Chimes, Third Quarter

"Never more, Meg; never more! Here! here! Close to you, holding to you,

feeling your dear breath upon my face!"—The Chimes, Third Quarter

"Whither thou goest, I can not go; where thou lodgest, I do not lodge; thy

people are not my people; nor thy God, my God!"—The Chimes, Third Quarter

"Whither thou goest, I can not go; where thou lodgest, I do not lodge; thy

people are not my people; nor thy God, my God!"—The Chimes, Third Quarter

"You're in spirits Tugby, my dear," observed his wife. . . . "No," said Tugby. "No; not particular.

I'm a little elevated. The muffins came so pat!"—The Chimes, Fourth Quarter

"You're in spirits Tugby, my dear," observed his wife. . . . "No," said Tugby. "No; not particular.

I'm a little elevated. The muffins came so pat!"—The Chimes, Fourth Quarter

John Peerybingle's fireside—The Cricket on the Hearth, Chirp the first

John Peerybingle's fireside—The Cricket on the Hearth, Chirp the first

"Did its mother make it up a beds, then!" cried Miss Slowboy to the baby;

"and did its hair grow brown and curly when its caps was lifted off, and

frighten it, a precious pets, a sitting by the fires!"—The Cricket on the Hearth,

Chirp the first

"Did its mother make it up a beds, then!" cried Miss Slowboy to the baby;

"and did its hair grow brown and curly when its caps was lifted off, and

frighten it, a precious pets, a sitting by the fires!"—The Cricket on the Hearth,

Chirp the first

"The extent to which he's winking at this moment!" whispered Caleb to his

daughter. "Oh, my gracious!"—The Cricket on the Hearth, Chirp the second

"The extent to which he's winking at this moment!" whispered Caleb to his

daughter. "Oh, my gracious!"—The Cricket on the Hearth, Chirp the second

Suffering him to clasp her round the waist, as they moved slowly down the dim wooden

gallery—The Cricket on the Hearth, Chirp the second

Suffering him to clasp her round the waist, as they moved slowly down the dim wooden

gallery—The Cricket on the Hearth, Chirp the second

After dinner Caleb sang the song about the sparkling bowl—The Cricket on the

Hearth, Chirp the third

After dinner Caleb sang the song about the sparkling bowl—The Cricket on the

Hearth, Chirp the third

The ploughshare still turned up, from time to time, some rusty bits of metal, but it was hard to

say what use they had ever served, and those who found them wondered and disputed—The Battle

of Life, Part the first

The ploughshare still turned up, from time to time, some rusty bits of metal, but it was hard to

say what use they had ever served, and those who found them wondered and disputed—The Battle

of Life, Part the first

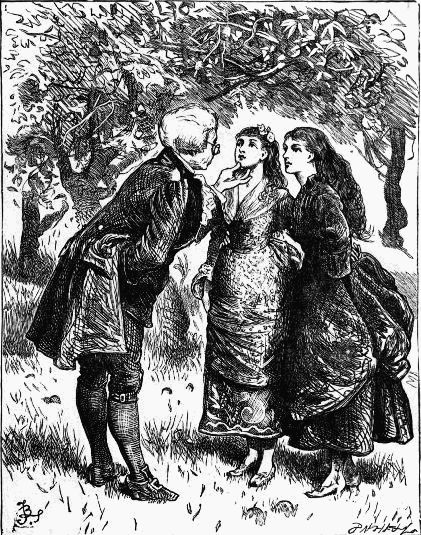

"By the bye," and he looked into the pretty face, still close to his, "I

suppose it's your birthday"—The Battle of Life, Part the first

"By the bye," and he looked into the pretty face, still close to his, "I

suppose it's your birthday"—The Battle of Life, Part the first

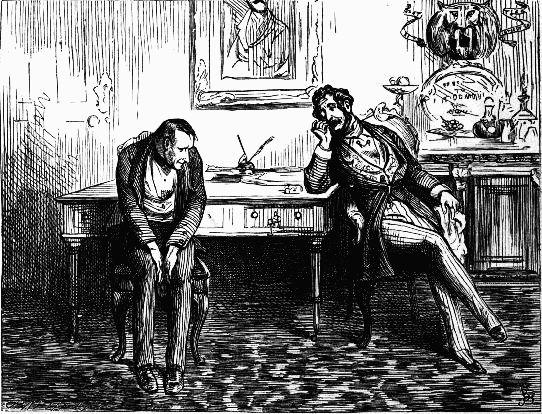

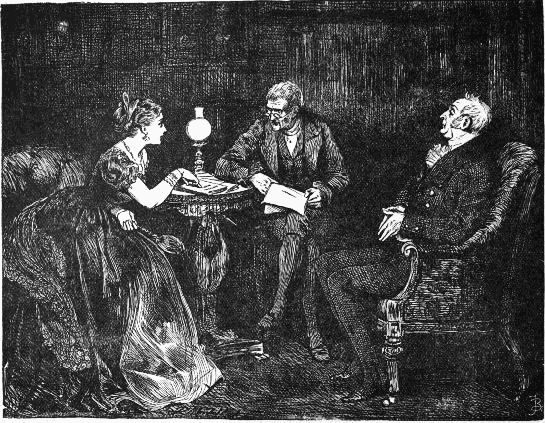

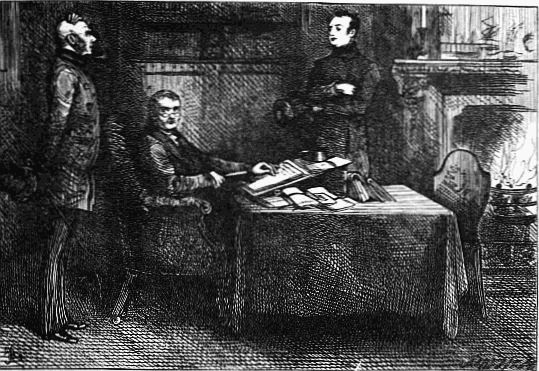

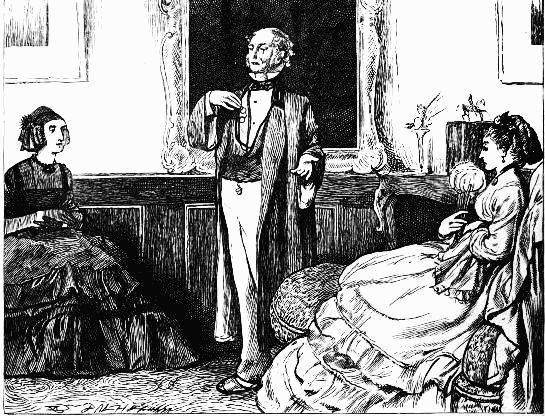

"I think it will be better not to hear this, Mr. Craggs!" said Snitchey,

looking at him across the client. "I think not," said Craggs—both

listening attentively—The Battle of Life, Part the second

"I think it will be better not to hear this, Mr. Craggs!" said Snitchey,

looking at him across the client. "I think not," said Craggs—both

listening attentively—The Battle of Life, Part the second

Guessed half aloud, "milk and water," "monthly warning," "mice and walnuts"—and couldn't

approach her meaning—The Battle of Life, Part the third

Guessed half aloud, "milk and water," "monthly warning," "mice and walnuts"—and couldn't

approach her meaning—The Battle of Life, Part the third

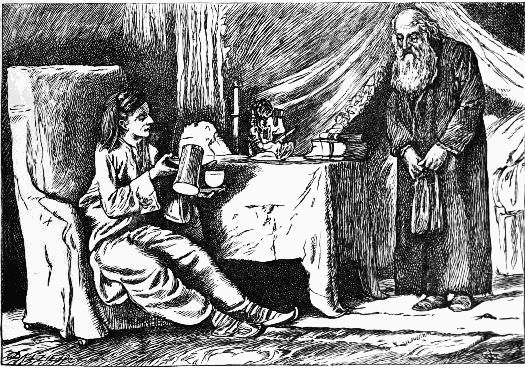

"Merry and happy, was it?" asked the chemist in a low voice. "Merry and

happy old man!"—The Haunted Man, chap. i.

"Merry and happy, was it?" asked the chemist in a low voice. "Merry and

happy old man!"—The Haunted Man, chap. i.

It roved from door-step to door-step, in the arms of little Johnny Tetterby,

and lagged heavily at the rear of troops of juveniles who followed the

tumblers, etc.—The Haunted Man, chap. ii.

It roved from door-step to door-step, in the arms of little Johnny Tetterby,

and lagged heavily at the rear of troops of juveniles who followed the

tumblers, etc.—The Haunted Man, chap. ii.

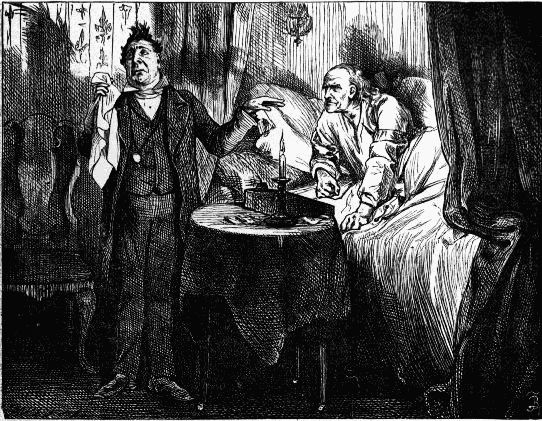

"Mr. Redlaw!" he exclaimed, and started up—The Haunted Man, chap. ii.

"Mr. Redlaw!" he exclaimed, and started up—The Haunted Man, chap. ii.

"I'm not a-going to take you there. Let me be or I'll heave some fire at you!"—The Haunted Man,

chap. ii.

"I'm not a-going to take you there. Let me be or I'll heave some fire at you!"—The Haunted Man,

chap. ii.

"You speak to me of what is lying here," the phantom interposed, and pointed

with its finger to the boy—The Haunted Man, chap. iii.

"You speak to me of what is lying here," the phantom interposed, and pointed

with its finger to the boy—The Haunted Man, chap. iii.

"What a wonderful man you are, father! How are you father? are you

really pretty hearty, though?" said William, shaking hands with him

again, and patting him again, and rubbing him gently down again—The

Haunted Man, chap. iii.

"What a wonderful man you are, father! How are you father? are you

really pretty hearty, though?" said William, shaking hands with him

again, and patting him again, and rubbing him gently down again—The

Haunted Man, chap. iii.

The sedate face in the portrait, with the beard and ruff, looked down at

them—The Haunted Man, chap. iii.

The sedate face in the portrait, with the beard and ruff, looked down at

them—The Haunted Man, chap. iii.

The Malle Post—Going Through France

The Malle Post—Going Through France

Playing at Mora—Genoa and its Neighbourhood

Playing at Mora—Genoa and its Neighbourhood

The Church and the World—To Parma, Modena, and Bologna

The Church and the World—To Parma, Modena, and Bologna

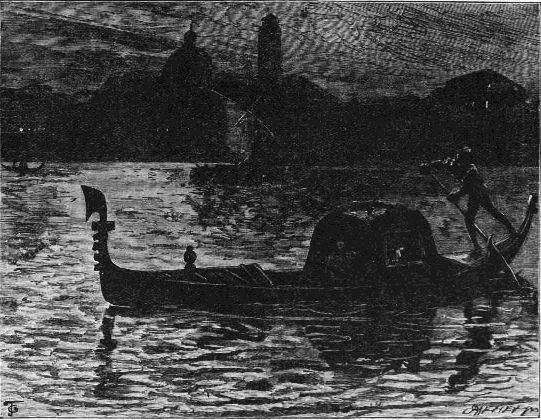

An Italian Dream

An Italian Dream

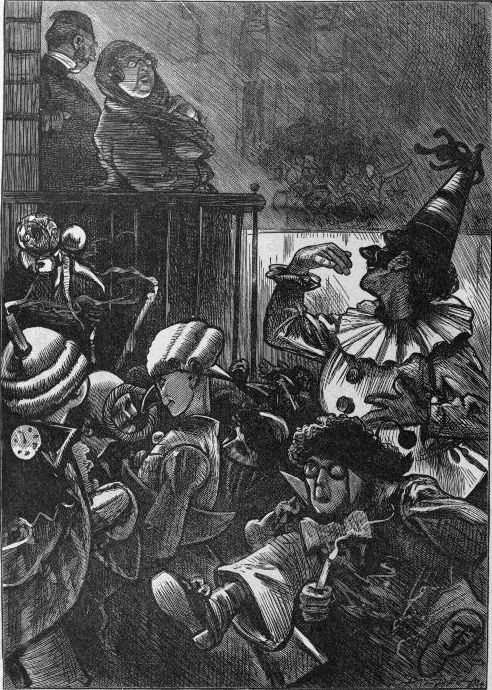

A sketch at the carnival—Rome

A sketch at the carnival—Rome

Artists' models—Rome

Artists' models—Rome

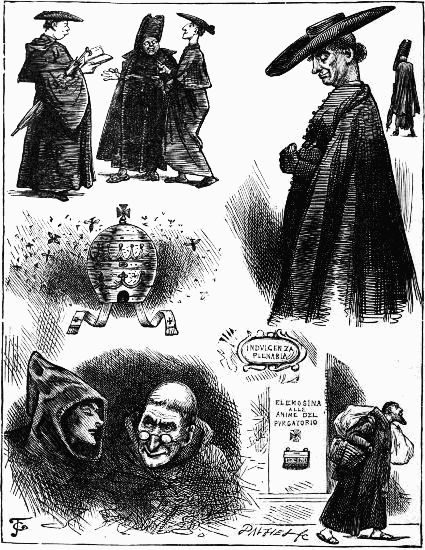

Priests and monks—A Rapid Diorama

Priests and monks—A Rapid Diorama

A thorough contrast in all respects to Mr. Dombey—Chap. ii.

A thorough contrast in all respects to Mr. Dombey—Chap. ii.

"I may be fond of pennywinkles, Mrs. Richards, but it don't follow that I'm to

have 'em for tea"—Chap. iii.

"I may be fond of pennywinkles, Mrs. Richards, but it don't follow that I'm to

have 'em for tea"—Chap. iii.

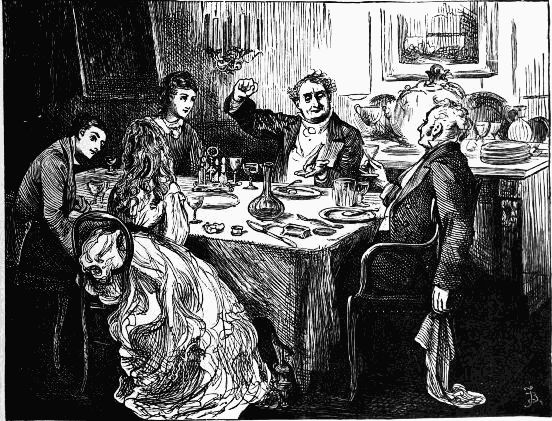

"So here's to Dombey—and son—and daughter"—Chap. iv.

"So here's to Dombey—and son—and daughter"—Chap. iv.

Mr. Dombey dismounting first to help the ladies out—Chap. v.

Mr. Dombey dismounting first to help the ladies out—Chap. v.

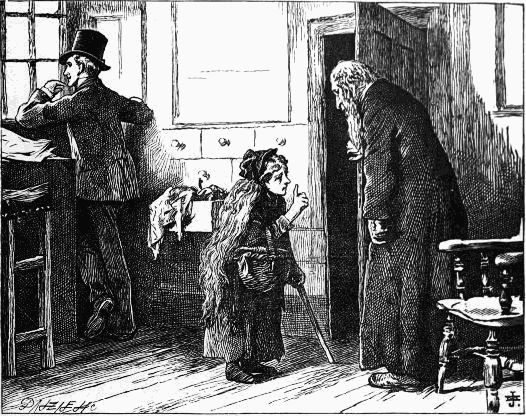

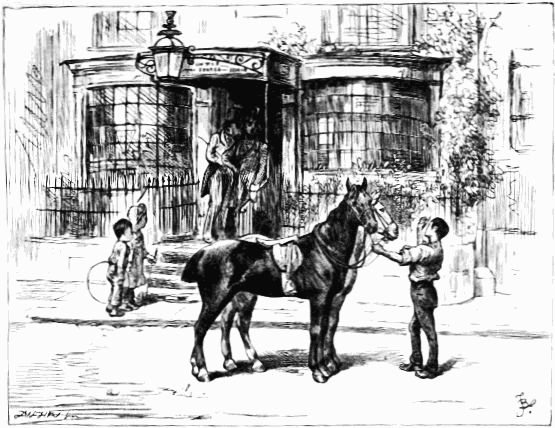

"Why, what can you want with Dombey and Son's!" . . . "To know the way there, if you please."—Chap. vi.

"Why, what can you want with Dombey and Son's!" . . . "To know the way there, if you please."—Chap. vi.

Florence obeyed as fast as her trembling hands would allow; keeping, all the while, a frightened

eye on Mrs. Brown—Chap. vi.

Florence obeyed as fast as her trembling hands would allow; keeping, all the while, a frightened

eye on Mrs. Brown—Chap. vi.

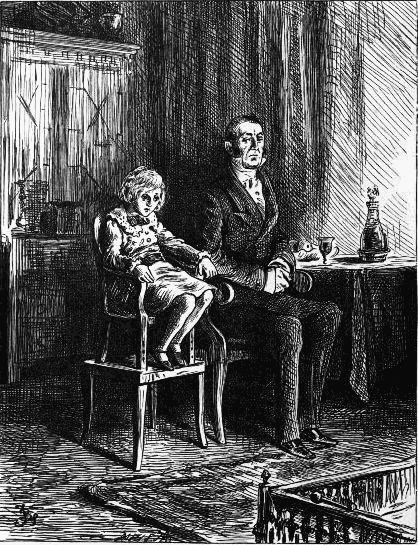

Dombey and Son—Chap. viii.

Dombey and Son—Chap. viii.

Listening to the sea—Chap. viii.

Listening to the sea—Chap. viii.

And when he got there, sat down in a chair, and fell into a silent fit of

laughter with which he was sometimes seized, and which was always particularly

awful—Chap. x.

And when he got there, sat down in a chair, and fell into a silent fit of

laughter with which he was sometimes seized, and which was always particularly

awful—Chap. x.

When the doctor smiled auspiciously at his author, or knit his brows, or shook his head and made

wry faces at him, as much as to say, "Don't tell me, sir; I know better," it was terrific—Chap. xi.

When the doctor smiled auspiciously at his author, or knit his brows, or shook his head and made

wry faces at him, as much as to say, "Don't tell me, sir; I know better," it was terrific—Chap. xi.

"Your father's regularly rich, ain't he!" inquired Mr. Toots.

"Yes, sir," said Paul; "He's Dombey and Son"—Chap. xii.

"Your father's regularly rich, ain't he!" inquired Mr. Toots.

"Yes, sir," said Paul; "He's Dombey and Son"—Chap. xii.

"You respect nobody, Carker, I think," said Mr. Dombey. "No!" inquired

Carker, with another wide and most feline show of his teeth—Chap. xiii.

"You respect nobody, Carker, I think," said Mr. Dombey. "No!" inquired

Carker, with another wide and most feline show of his teeth—Chap. xiii.

During this conversation, Walter had looked from one brother to the other with pain and

amazement—Chap. xiii.

During this conversation, Walter had looked from one brother to the other with pain and

amazement—Chap. xiii.

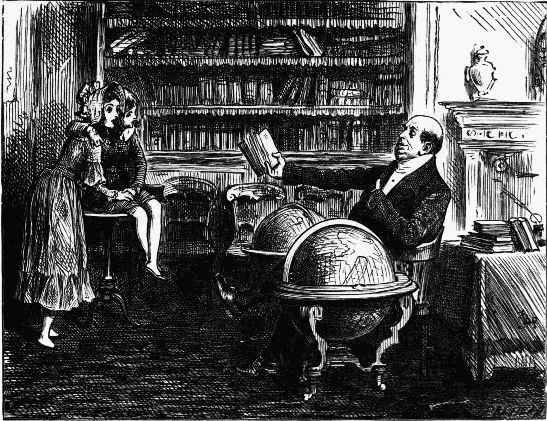

Paul also asked him, as a practical man, what he thought about King Alfred's idea of measuring

time by the burning of candles, to which the workman replied that he thought it would be the

ruin of the clock trade if it was to come up again—Chap. xiv.

Paul also asked him, as a practical man, what he thought about King Alfred's idea of measuring

time by the burning of candles, to which the workman replied that he thought it would be the

ruin of the clock trade if it was to come up again—Chap. xiv.

The breaking-up party at Doctor Blimber's—Chap. xiv.

The breaking-up party at Doctor Blimber's—Chap. xiv.

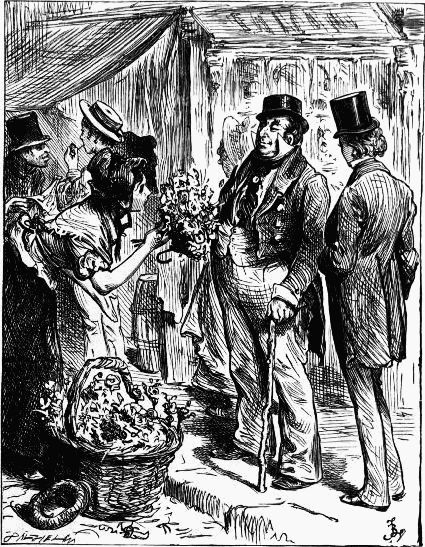

Before they had gone very far, they encountered a woman selling flowers:

when the captain, stopping short, as if struck by a happy idea, made a purchase

of the largest bundle in her basket—Chap. xv.

Before they had gone very far, they encountered a woman selling flowers:

when the captain, stopping short, as if struck by a happy idea, made a purchase

of the largest bundle in her basket—Chap. xv.

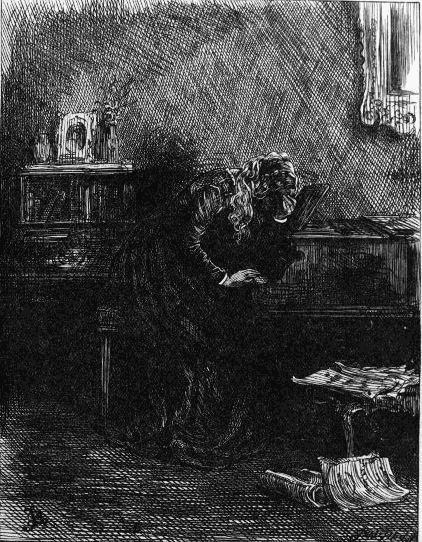

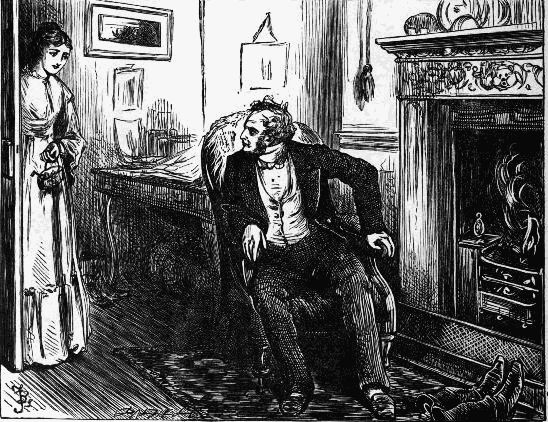

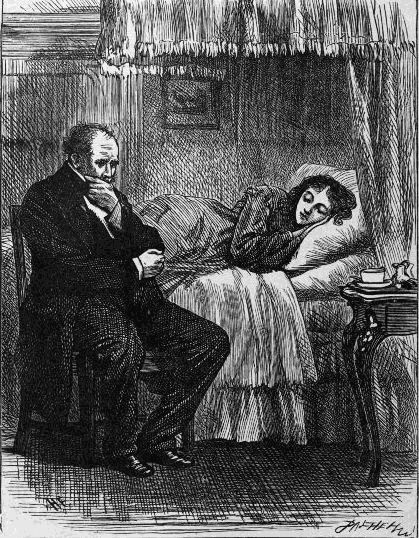

All this time, the bereaved father has not been seen even by his attendant;

for he sits in a corner of his own dark room—Chap. xviii.

All this time, the bereaved father has not been seen even by his attendant;

for he sits in a corner of his own dark room—Chap. xviii.

It was repeated often—very often, in the shadowy solitude; and broken

murmurs of the strain still trembled on the keys, when the sweet voice

was hushed in tears—Chap. xviii.

It was repeated often—very often, in the shadowy solitude; and broken

murmurs of the strain still trembled on the keys, when the sweet voice

was hushed in tears—Chap. xviii.

Took Uncle Sol's snuff-coloured lappels, one in each hand; kissed him on the

cheek, etc.—Chap. xix.

Took Uncle Sol's snuff-coloured lappels, one in each hand; kissed him on the

cheek, etc.—Chap. xix.

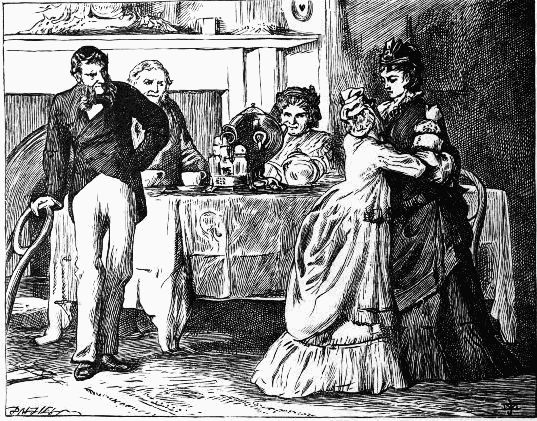

Withers the Wan, at this period, handing round the tea, Mr. Dombey again addressed himself to

Edith—Chap. xxi.

Withers the Wan, at this period, handing round the tea, Mr. Dombey again addressed himself to

Edith—Chap. xxi.

"Do you know that there is some one here!" she returned, now looking at him steadily—Chap. xxxvi.

"Do you know that there is some one here!" she returned, now looking at him steadily—Chap. xxxvi.

"Let you alone!" said Mr. Carker. "What! I have got you, have I!" There

was no doubt of that, and tightly too. "You dog," said Mr. Carker, through

his set jaws, "I'll strangle you!"—Chap. xxii.

"Let you alone!" said Mr. Carker. "What! I have got you, have I!" There

was no doubt of that, and tightly too. "You dog," said Mr. Carker, through

his set jaws, "I'll strangle you!"—Chap. xxii.

"What do you want with Captain Cuttle, I should wish to know!" said Mrs. Macstinger.

"Should you! Then I'm sorry that you won't be satisfied," returned Miss Nipper—Chap. xxiii.

"What do you want with Captain Cuttle, I should wish to know!" said Mrs. Macstinger.

"Should you! Then I'm sorry that you won't be satisfied," returned Miss Nipper—Chap. xxiii.

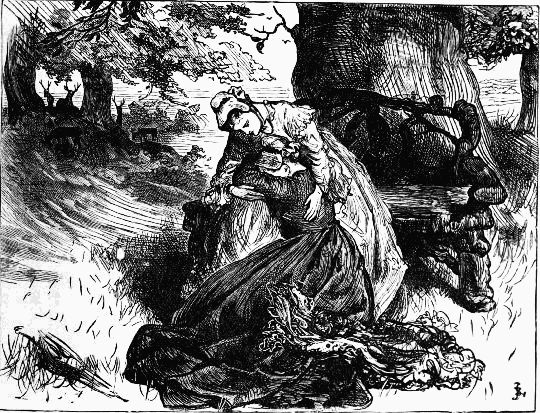

The flowers were scattered on the ground like dust; the empty hands were

spread upon the face; and orphaned Florence, shrinking down upon the

ground, wept long and bitterly—Chap. xxiv.

The flowers were scattered on the ground like dust; the empty hands were

spread upon the face; and orphaned Florence, shrinking down upon the

ground, wept long and bitterly—Chap. xxiv.

The Captain's voice was so tremendous, and he came out of his corner with such way on him, that

Rob retreated before him into another corner; holding out the keys and packet, to prevent himself

from being run down—Chap. xxv.

The Captain's voice was so tremendous, and he came out of his corner with such way on him, that

Rob retreated before him into another corner; holding out the keys and packet, to prevent himself

from being run down—Chap. xxv.

"Go and meet her!"—Chap. xxvii.

"Go and meet her!"—Chap. xxvii.

"Thank you. I have no desire to read it," was her answer—Chap. xxvi.

"Thank you. I have no desire to read it," was her answer—Chap. xxvi.

"A child!" said Edith, looking at her. "When was I a child! What

childhood did you ever leave to me!"—Chap. xxviii.

"A child!" said Edith, looking at her. "When was I a child! What

childhood did you ever leave to me!"—Chap. xxviii.

Lucretia Tox's reverie—Chap. xxix.

Lucretia Tox's reverie—Chap. xxix.

One of the very tall young men on hire, whose organ of veneration was imperfectly developed,

thrusting his tongue into his cheek, for the entertainment of the other very tall young man on

hire, as the couple turned into the dining-room—Chap. xxx.

One of the very tall young men on hire, whose organ of veneration was imperfectly developed,

thrusting his tongue into his cheek, for the entertainment of the other very tall young man on

hire, as the couple turned into the dining-room—Chap. xxx.

She started, stopped, and looked in—Chap. xxx.

She started, stopped, and looked in—Chap. xxx.

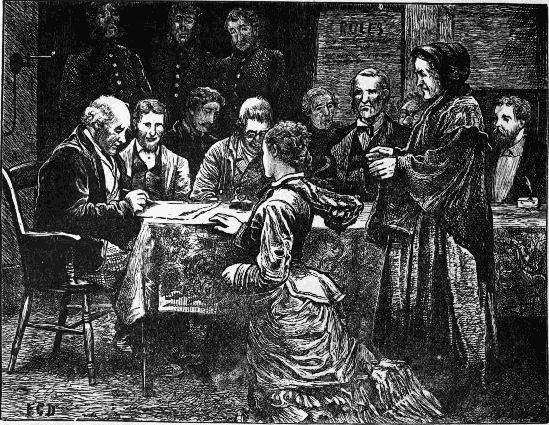

In a firm, free hand, the bride subscribes her name in the register—Chap. xxxi.

In a firm, free hand, the bride subscribes her name in the register—Chap. xxxi.

"Go," said the good-humoured manager, gathering up his skirts, and standing astride on the

hearth-rug, "like a sensible fellow, and let us have no turning out, or any such violent

measures"—Chap. xxxii.

"Go," said the good-humoured manager, gathering up his skirts, and standing astride on the

hearth-rug, "like a sensible fellow, and let us have no turning out, or any such violent

measures"—Chap. xxxii.

And reading softly to himself, in the little back parlour, and stopping now

and then to wipe his eyes, the Captain, in a true and simple spirit, committed

Walter's body to the deep—Chap. xxxii.

And reading softly to himself, in the little back parlour, and stopping now

and then to wipe his eyes, the Captain, in a true and simple spirit, committed

Walter's body to the deep—Chap. xxxii.

A certain skilful action of his fingers as he hummed some bars, and beat

time on the seat beside him, seemed to denote the musician—Chap. xxxiii.

A certain skilful action of his fingers as he hummed some bars, and beat

time on the seat beside him, seemed to denote the musician—Chap. xxxiii.

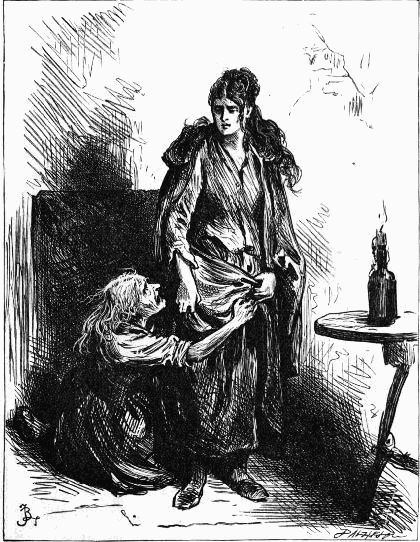

"She's come back harder than she went!" cried the mother, looking up in

her face, and still holding to her knees—Chap. xxxiv.

"She's come back harder than she went!" cried the mother, looking up in

her face, and still holding to her knees—Chap. xxxiv.

Withers, meeting him on the stairs, stood amazed at the beauty of his teeth,

and at his brilliant smile—Chap. xxxvii.

Withers, meeting him on the stairs, stood amazed at the beauty of his teeth,

and at his brilliant smile—Chap. xxxvii.

Ran sniggering off to get change, and tossed it away with a pieman—Chap. xxxviii.

Ran sniggering off to get change, and tossed it away with a pieman—Chap. xxxviii.

Mr. Toots replies by launching wildly out into Miss Dombey's praises, and by insinuations that

sometimes he thinks he should like to blow his brains out—Chap. xli.

Mr. Toots replies by launching wildly out into Miss Dombey's praises, and by insinuations that

sometimes he thinks he should like to blow his brains out—Chap. xli.

"Do you call it managing this establishment, madam," said Mr. Dombey, "to leave a person like

this at liberty to come and talk to me!"—Chap. xliv.

"Do you call it managing this establishment, madam," said Mr. Dombey, "to leave a person like

this at liberty to come and talk to me!"—Chap. xliv.

"Miss Dombey," returned Mr. Toots, "if you'll only name one, you'll—you'll

give me an appetite. To which," said Mr. Toots, with some sentiment, "I have

long been a stranger"—Chap. xliv.

"Miss Dombey," returned Mr. Toots, "if you'll only name one, you'll—you'll

give me an appetite. To which," said Mr. Toots, with some sentiment, "I have

long been a stranger"—Chap. xliv.

Flung it down, and trod upon the glittering heap—Chap. xlvii.

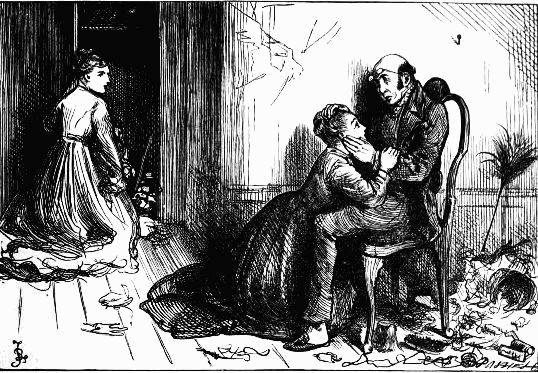

Flung it down, and trod upon the glittering heap—Chap. xlvii.

Thrown down in a costly mass upon the ground was every ornament she had

had since she had been his wife; every dress she had worn; and everything

she had possessed—Chap. xlvii.

Thrown down in a costly mass upon the ground was every ornament she had

had since she had been his wife; every dress she had worn; and everything

she had possessed—Chap. xlvii.

Florence made a motion with her hand towards him, reeled and fell upon the floor—Chap. xlviii.

Florence made a motion with her hand towards him, reeled and fell upon the floor—Chap. xlviii.

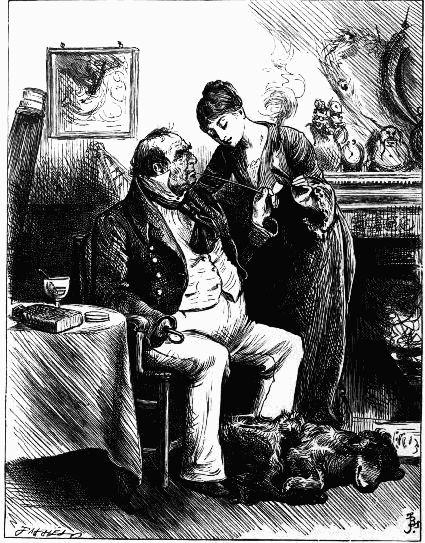

When he had filled his pipe in an absolute reverie of satisfaction,

Florence lighted it for him—Chap. xlix.

When he had filled his pipe in an absolute reverie of satisfaction,

Florence lighted it for him—Chap. xlix.

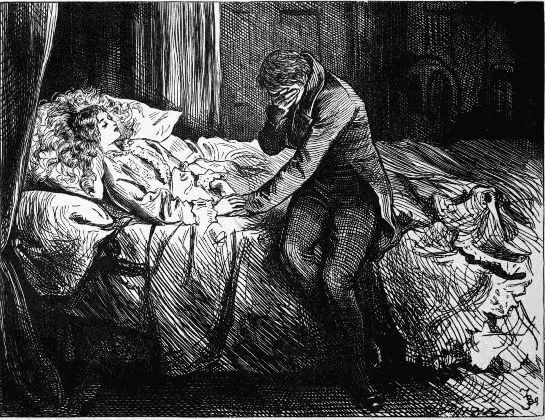

Blessed twilight stealing on, and shading her so soothingly and gravely as

she falls asleep, like a hushed child, upon the bosom she has clung to!—Chap. l.

Blessed twilight stealing on, and shading her so soothingly and gravely as

she falls asleep, like a hushed child, upon the bosom she has clung to!—Chap. l.

It appears that he met everybody concerned in the late transaction, everywhere, and said to

them, "Sir," or "Madam," as the case was, "Why do you look so pale!" at which each shuddered

from head to foot, and said, "Oh, Perch!" and ran away—Chap. li.

It appears that he met everybody concerned in the late transaction, everywhere, and said to

them, "Sir," or "Madam," as the case was, "Why do you look so pale!" at which each shuddered

from head to foot, and said, "Oh, Perch!" and ran away—Chap. li.

D. I. J. O. N—Chap. lii.

D. I. J. O. N—Chap. lii.

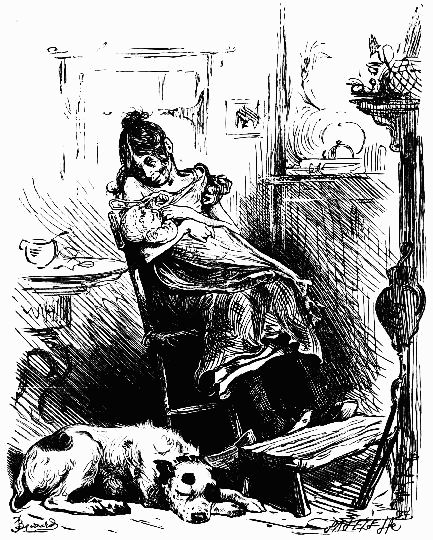

Still upon her knees, and with her eyes upon the fire—Chap. liii.

Still upon her knees, and with her eyes upon the fire—Chap. liii.

He saw the face change from its vindictive passion to a faint sickness and terror—Chap. lv.

He saw the face change from its vindictive passion to a faint sickness and terror—Chap. lv.

After this, he smoked four pipes successively in the little parlour by

himself, and was discovered chuckling at the expiration of as many

hours—Chap. lvi.

After this, he smoked four pipes successively in the little parlour by

himself, and was discovered chuckling at the expiration of as many

hours—Chap. lvi.

"Wy, it's mean . . . . that's where it is. It's mean!"—Chap. lvi.

"Wy, it's mean . . . . that's where it is. It's mean!"—Chap. lvi.

"Yes, Mrs. Pipchin, it is," replies cook, advancing. "And what then pray!"—Chap. lix.

"Yes, Mrs. Pipchin, it is," replies cook, advancing. "And what then pray!"—Chap. lix.

"Oh, my God, forgive me, for I need it very much!"—Chap. lix.

"Oh, my God, forgive me, for I need it very much!"—Chap. lix.

"No, no!" cried Florence, shrinking back as she rose up, and putting out her

hands to keep her off. "Mamma!"—Chap. lxi.

"No, no!" cried Florence, shrinking back as she rose up, and putting out her

hands to keep her off. "Mamma!"—Chap. lxi.

Captain Cuttle gives them the Lovely Peg—Chap. lxii.

Captain Cuttle gives them the Lovely Peg—Chap. lxii.

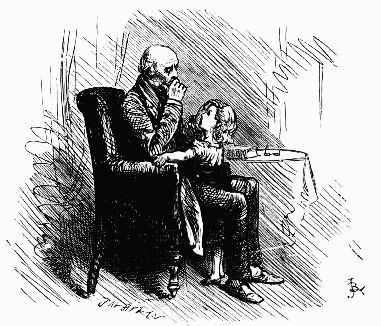

"Dear Grandpapa, why do you cry when you kiss me?"—Chap. lxii.

"Dear Grandpapa, why do you cry when you kiss me?"—Chap. lxii.

"Dead, Mr. Peggotty!" I hinted, after a respectful pause.

"Dead, Mr. Peggotty!" I hinted, after a respectful pause.

"That's not it!" said I, "that ship-looking thing!" "That's it, Mas'r Davy," returned Ham—Chap. iii.

"That's not it!" said I, "that ship-looking thing!" "That's it, Mas'r Davy," returned Ham—Chap. iii.

I saw to my amazement, Peggotty burst from a hedge and climb into the cart—Chap. v.

I saw to my amazement, Peggotty burst from a hedge and climb into the cart—Chap. v.

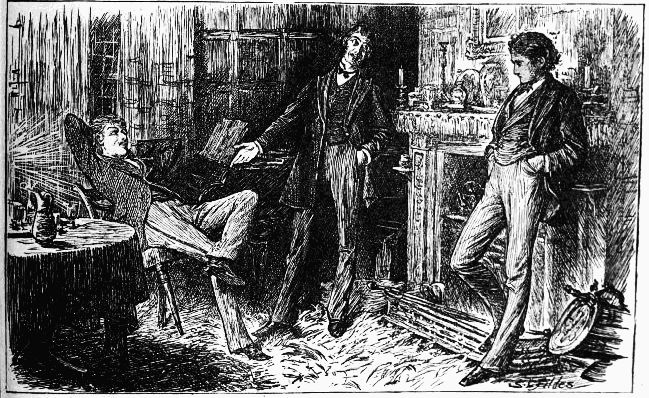

"Let him deny it," said Steerforth—Chap. vii.

"Let him deny it," said Steerforth—Chap. vii.

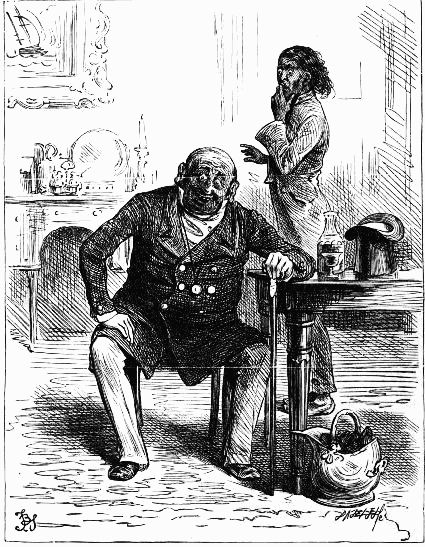

"Father!" said Minnie playfully. "What a porpoise you do grow!"—Chap. ix.

"Father!" said Minnie playfully. "What a porpoise you do grow!"—Chap. ix.

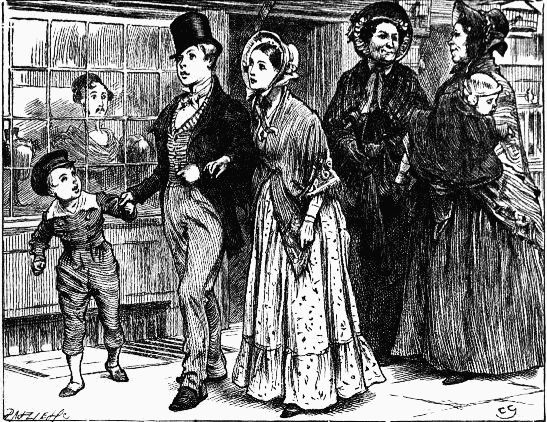

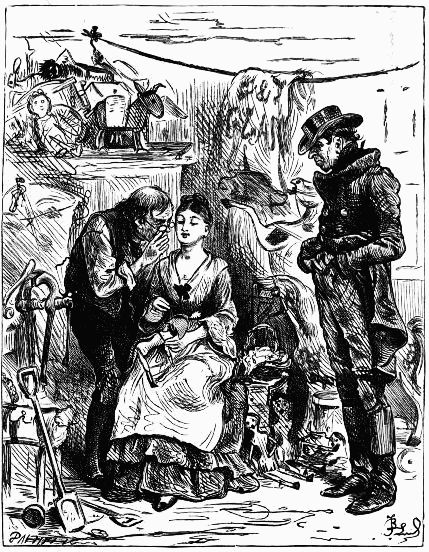

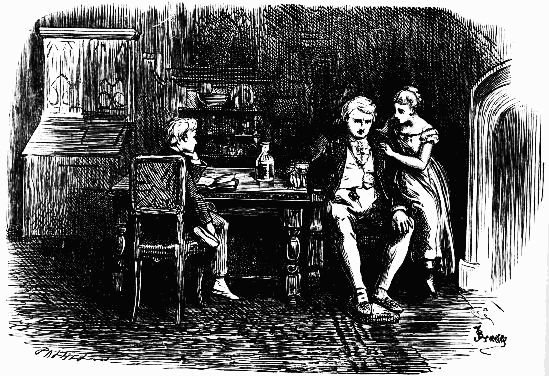

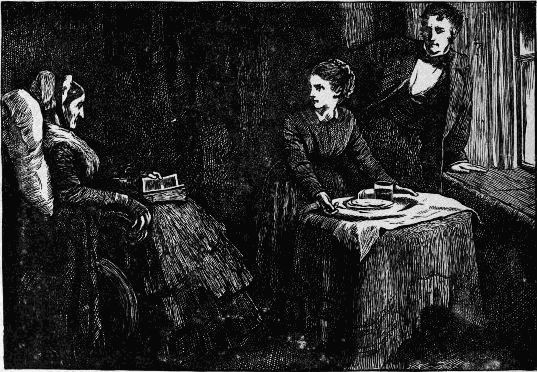

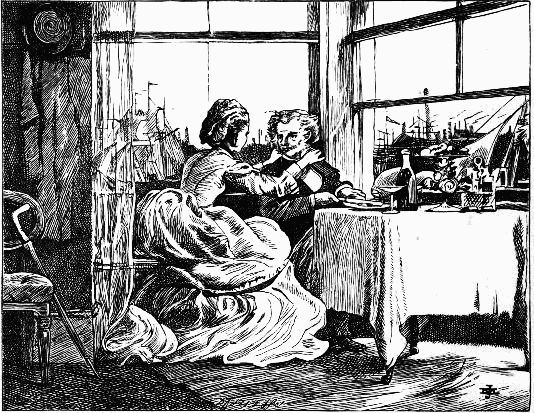

I am presented to Mrs. Micawber—Chap. xi.

I am presented to Mrs. Micawber—Chap. xi.

"Oh, my lungs and liver, will you go for threepence!"—Chap. xiii.

"Oh, my lungs and liver, will you go for threepence!"—Chap. xiii.

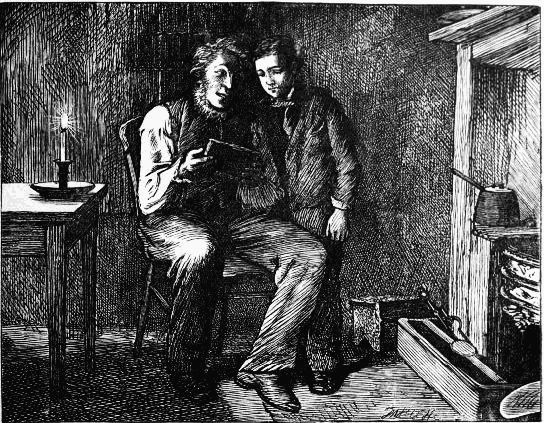

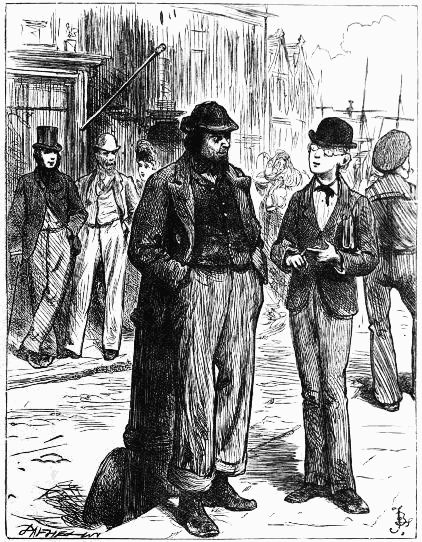

Mr. Micawber, impressing the names of the streets and the shapes of corner houses upon me as we

went along, that I might find my way back easily in the morning—Chap. xi.

Mr. Micawber, impressing the names of the streets and the shapes of corner houses upon me as we

went along, that I might find my way back easily in the morning—Chap. xi.

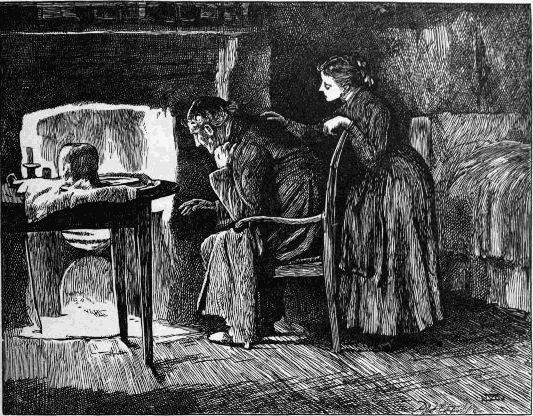

She always roused him with a question or caress—Chap. xv.

She always roused him with a question or caress—Chap. xv.

The doctor's walk—Chap. xvii.

The doctor's walk—Chap. xvii.

"Oh, really! you know how ignorant I am, and that I only ask for information, but isn't it always

so! I thought that kind of life was on all hands understood to be—eh!"—Chap. XX.

"Oh, really! you know how ignorant I am, and that I only ask for information, but isn't it always

so! I thought that kind of life was on all hands understood to be—eh!"—Chap. XX.

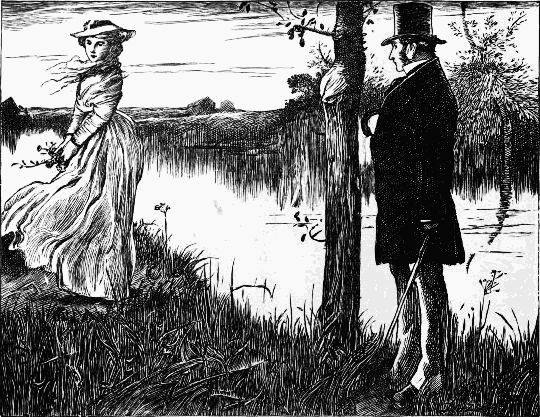

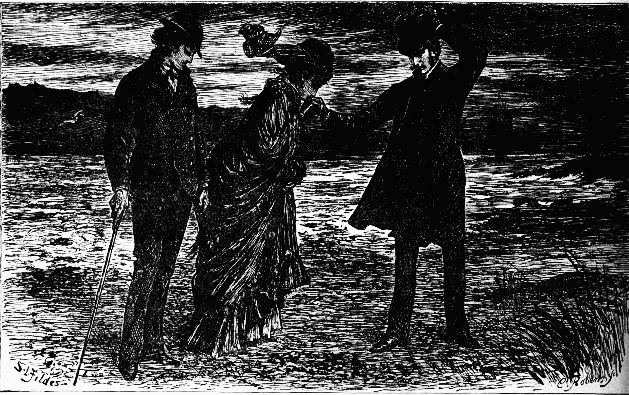

"That is a black shadow to be following the girl," said Steerforth, standing still; "what does

it mean!"—Chap. xxii.

"That is a black shadow to be following the girl," said Steerforth, standing still; "what does

it mean!"—Chap. xxii.

And Mrs. Crupp said, thank heaven she had now found summun she could care for—Chap. xxiii.

And Mrs. Crupp said, thank heaven she had now found summun she could care for—Chap. xxiii.

Dora—Chap. xxvi.

Dora—Chap. xxvi.

Mr. Micawber in his element—Chap. xxviii.

Mr. Micawber in his element—Chap. xxviii.

"Give me breath enough," says I to my daughter Minnie, "and I'll find passages, my dear"—Chap. xxx

"Give me breath enough," says I to my daughter Minnie, "and I'll find passages, my dear"—Chap. xxx

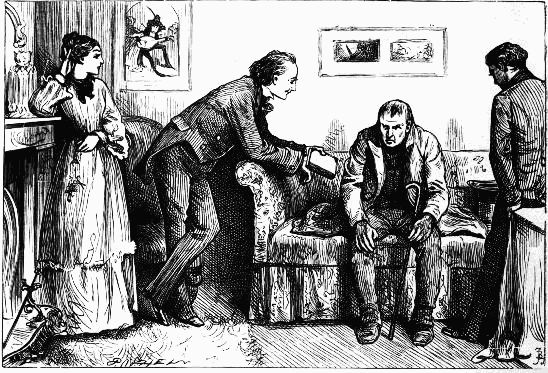

"Read it, sir," he said, in a low shivering voice. "Slow, please. I doen't know as I can understand"—Chap. xxxi.

"Read it, sir," he said, in a low shivering voice. "Slow, please. I doen't know as I can understand"—Chap. xxxi.

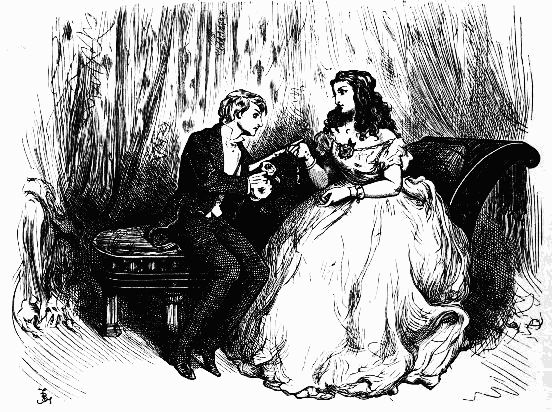

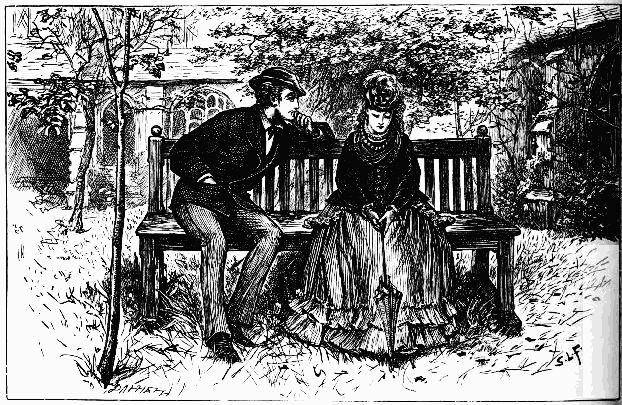

Under the lilac tree—Chap. xxxiii.

Under the lilac tree—Chap. xxxiii.

"Deuce take the man!" said my aunt sternly, "what's he about! don't be galvanic, sir!"—Chap. xxxv.

"Deuce take the man!" said my aunt sternly, "what's he about! don't be galvanic, sir!"—Chap. xxxv.

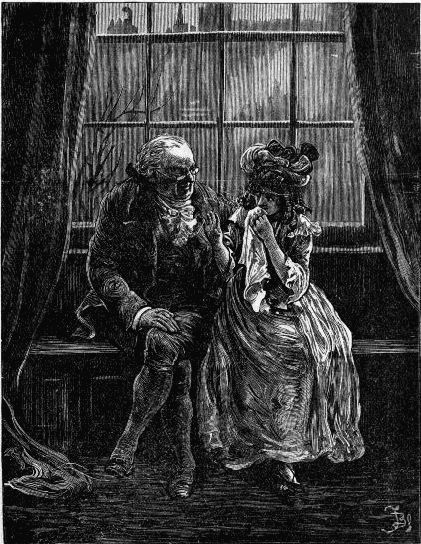

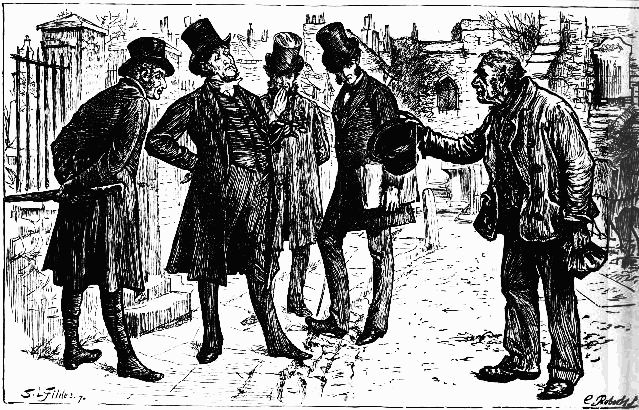

"You have heard Miss Murdstone," said Mr. Spenlow, turning to me. "I beg to ask Mr. Copperfield,

if you have anything to say in reply!"—Chap. xxxviii.